The books reviewed this week are part of the Pen & Sword series of publications. Earlier reviews from the series were A Visitor’s Guide to Jane Austen’s England by Sue Wilkes; London and the Seventeenth Century by Margarette Lincoln and Michelle Higgins’ A Visitor’s Guide to Victorian England. This is a series that makes history accessible, at the same time as being well researched and complete with bibliographies, citations and indexes. Net Galley and Pen& Sword have been generous in providing me with early proofs of the books. The two that I review this week are biographies: The Real George Eliot by Lisa Tippings and The Real Diana Dors by Anna Cale. I found the biographies less satisfying than the guides, but both had some positive features. To illustrate the breadth of the biographies covered by this imprint, I have just finished reading The Rebel Suffragette, The Life of Edith Rigby by Beverley Adams, which will be reviewed later.

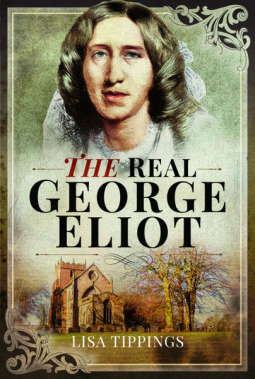

Lisa Tippings, The Real George Eliot, Pen & Sword History, 2021. When I read the introduction to this book, I felt a surge of enthusiasm for Lisa Tippings’ similar enthusiastic embrace of her material, evidenced by her early introduction to George Eliot’s work, her journeys to relevant sites and her commentary on the early stages of her research. She begins with a George Eliot quote from Middlemarch, ‘What do we live for, if it is not to make life less difficult to each other?’ Following is a warm introduction to Lisa Tippings, her Welsh childhood, including watching BBC costume dramas, and the way in which her imagination was caught by Maggie Tulliver, and remembered discussions unhampered by academic demands. Then, the travelling associated with the work – including Nuneaton, The Red Lion (Bull Inn), The George Eliot Hotel, the George Eliot statue in Newdegate Square, Arbury Hall (closed) and Astley. All these locations are beautifully realised so that the reader joins Tippings’ journey into the life of George Elliot. For complete review see Books: Reviews

Anna Cale, The Real Diana Dors, White Owl, Pen & Sword Books Ltd, 2021. I have mixed feelings about this story of Diana Dors’ life. While reading I wondered if her life was significant enough to sustain a full-length book and must admit to feeling a sense of despair as the love affairs, marriages, money troubles rolled out, seemingly unendingly. I have looked beyond these to try to see what was remarkable enough for Anna Cale to argue that there is a ‘real’ Diana Dors we do not know. The feature of the book that sustained my interest was the history of the British film industry in the period in which Dors made her early career. In addition, Cale’s perceptiveness in her discussion in Chapter 12 ends the book well. For complete review see Books: Reviews

Amanda Lohrey wins Miles Franklin prize for The Labyrinth. The Guardian Thu 15 Jul 2021 16.31 AEST

The 74-year-old Tasmanian writer collected the prize for her seventh novel, described as eerie, unsettling and soaked in sadness

Supported by

Tasmanian writer Amanda Lohrey has collected her first Miles Franklin Literary Award, at the age of 74.

Although a nominee on a number of occasions, and the recipient of other notable gongs over the years such as the Patrick White prize and the Victorian premier’s literary award, it has taken a lifetime for Lohrey to snag what is arguably the most prestigious prize for Australian writing, with her seventh novel The Labyrinth.

The $60,000 win was announced on Thursday via live stream for the second year in a row, due to Covid-19 restrictions.

Miles Franklin judge and Mitchell Librarian of the State Library of NSW, Richard Neville, described The Labyrinth as “an elegiac novel, soaked in sadness”.

It tells the story of a woman who moves to a remote rural community to be closer to her son, who is serving time in jail for homicidal negligence. She comes to know her neighbours, but not necessarily like them, when she embarks on building a stone labyrinth, in an attempt to make sense of the loss and isolation in her life.

“It is a beautifully written reflection on the conflicts between parents and children, men and women, and the value and purpose of creative work,” Neville said.

Speaking to Guardian Australia, Lohrey said while she was drawn to political themes in her earlier works of fiction, as she has matured as a writer she has become more intrigued with the internal journeys people make in their lives.

“I’ve called [The Labyrinth] a pastoral, because I wanted to explore the tree change and the sea change [phenomena] which is actually a centuries-old move,” she said.

“People have always tried to escape into some kind of primeval landscape of rural virtue, in order to restore some damaged part of themselves.”

The fact that Lohrey’s central character of Erica Marsden chooses to build a stone labyrinth – as opposed to a maze – to repair the broken part of herself is significant.

“A maze is a puzzle, it’s a test of your intellect, it has a lot of dead ends, you can get lost,” she said.

“A labyrinth has one path in and the same path out. It can be a very complex path that loops around and takes you a while to get to the centre – and a while to get back out – but you can’t get lost … you will always find your way out.”

Guardian book reviewer Bec Kavanagh describes The Labyrinth as a “sharply tuned novel” and a “sprawling narrative that resists rigid expectations”.

“The Labyrinth offers a pull towards the unknown and a comfort in solitude,” Kavanagh wrote in August last year.

“Despite sometimes eerie loneliness, the book is quietly compelling, a carefully planned reflection on the many ways that we might retrace and remake ourselves and our relationships.”

Lohrey said the novel, published by Text Publishing, had been well received widely, but declined to say whether she believes The Labyrinth is her best work yet.

“I have had a tremendous amount of positive feedback, particularly from book groups and book clubs, they can often be very critical,” she said.

“But my novels are all very different, and it’s very hard to be objective about your own work.

“And of course the reader is the co-creator of the book, they bring 50% to it. And so the book is different for each reader.

“It’s fascinating when you go to book clubs as a guest and you hear them argue about your book and you think, ‘was that the book I wrote?’, because people reading fiction, it’s such a deeply subjective experience.”

Female writers have dominated the Miles Franklin Literary award for the past decade. Only one male writer, Serbian-born A S Patrić [Black Rock White City], has been awarded the prize in the past 10 years – in 2016.

“Funnily enough, since the Stella prize [introduced in 2013 to recognise female writers, and a response to the traditional male dominance in Australian literary prizes], more women have won the Miles Franklin than men,” said Lohrey.

“I don’t think anyone now in the current climate would bother setting up any more gender-specific prizes, we’ve got one, and that’s enough,” she said.

“But good on the Stella, the more prizes the better. We need all the prizes we can get in Australia, it’s a small market, and even writers that are well reviewed and sell moderately well are still not making a good living.

“A dollar prize really sets you up to write your next book.”

Like most writers, Lohrey is loth to discuss the book she is now working on, although she is happy to reveal it is already half-finished.

“Writers are deeply superstitious creatures, and also what you think the novel is about often times [it] turns out to be about something else,” she said.

“It kind of evolves as you go along and that’s that’s the fun of it, you never know where you’re going end.

“It’s a very playful exercise, even though there’s a lot of anguish along the way because, like a maze, you can go up a lot of your own dead ends, before you get where you need to go.”

Event at Wigmore Hall

Watch again: Lady Antonia Fraser in conversation with Hugo Vickers

Lady Antonia Fraser in conversation with Hugo Vickers

Acclaimed biographer and historical writer Lady Antonia Fraser discusses her life-long love of music and literature with the author and broadcaster Hugo Vickers. Their conversation will touch on the life of Caroline Norton, a pioneering women’s rights activist and the subject of Lady Antonia Fraser’s new book ‘The Case of the Married Woman’. This event also includes a performance from Kitty Whately and Simon Lepper of ‘Lady Antonia’s Songs’, a collection of four new songs composed by Stephen Hough, setting verse by Lady Antonia Fraser.WATCH

Heather Cox Richardson heather.richardson@bc.edu

July 17, 2021 (Saturday)

A year ago tonight, Georgia Representative John Lewis passed away from pancreatic cancer at 80 years old. As a young adult, Lewis was a “troublemaker,” breaking the laws of his state: the laws upholding racial segregation. He organized voting registration drives and in 1960 was one of the thirteen original Freedom Riders, white and Black students traveling together from Washington, D.C., to New Orleans to challenge segregation. “It was very violent. I thought I was going to die. I was left lying at the Greyhound bus station in Montgomery unconscious,” Lewis later recalled.

An adherent of the philosophy of nonviolence, Lewis was beaten by mobs and arrested 24 times. As chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC—pronounced “snick”), he helped to organize the 1963 March on Washington where the Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr., told more than 200,000 people gathered at the foot of the Lincoln Memorial that he had a dream. Just 23 years old, Lewis spoke at the march. Two years later, as Lewis and 600 marchers hoping to register African American voters in Alabama stopped to pray at the end of the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, mounted police troopers charged the marchers, beating them with clubs and bullwhips. They fractured Lewis’s skull.

To observers in 1965 reading the newspapers, Lewis was simply one of the lawbreaking protesters who were disrupting the “peace” of the South. But what seemed to be fruitless and dangerous protests were, in fact, changing minds. Shortly after the attack in Selma, President Lyndon Baines Johnson honored those changing ideas when he went on TV to support the marchers and call for Congress to pass a national voting rights bill. On August 6, 1965, Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act authorizing federal supervision of voter registration in districts where African Americans were historically underrepresented.

When Congress passed the Voting Rights Act, just 6.7 percent of Black voters in Mississippi were registered to vote. Two years later, almost 60% of them were. In 1986, those new Black voters helped to elect Lewis to Congress. He held the seat until he died, winning reelection 16 times.Now, just a year after Representative Lewis’s death, the voting rights for which he fought are under greater threat than they have been since 1965. After the 2013 Shelby County v. Holder decision of the Supreme Court gutted the Voting Rights Act by taking away Department of Justice supervision of election changes in states with a history of racial discrimination, Republican-dominated state legislatures began to enact measures that would cut down on minority voting.

At Representative Lewis’s funeral, former President Barack Obama called for renewing the Voting Rights Act. “You want to honor John?” he said. “Let’s honor him by revitalizing the law that he was willing to die for.” Instead, after the 2020 election, Republican-dominated legislatures ramped up their effort to skew the vote in their favor by limiting access to the ballot. As of mid-June 2021, 17 states had passed 28 laws making it harder to vote, while more bills continue to move forward.

Then, on July 1, by a 6-3 vote, the Supreme Court handed down Brnovich v. Democratic National Committee, saying that the state of Arizona did not violate the 1965 Voting Rights Act when it passed laws that limited ballot delivery to voters, family members, or caregivers, or when it required election officials to throw out ballots that voters had cast in the wrong precincts by accident.

The fact that voting restrictions affect racial or ethnic groups differently does not make them illegal, Justice Samuel Alito wrote. “The mere fact that there is some disparity in impact does not necessarily mean that a system is not equally open or that it does not give everyone an equal opportunity to vote.”

Justice Elena Kagan wrote a blistering dissent, in which Justices Stephen Breyer and Sonia Sotomayor joined. “If a single statute represents the best of America, it is the Voting Rights Act,” Kagan wrote, “It marries two great ideals: democracy and racial equality. And it dedicates our country to carrying them out.” She explained, “The Voting Rights Act is ambitious, in both goal and scope. When President Lyndon Johnson sent the bill to Congress, ten days after John Lewis led marchers across the Edmund Pettus Bridge, he explained that it was “carefully drafted to meet its objective—the end of discrimination in voting in America.” It gave every citizen “the right to an equal opportunity to vote.”

“Much of the Voting Rights Act’s success lay in its capacity to meet ever-new forms of discrimination,” Kagan wrote. Those interested in suppressing the vote have always offered “a non-racial rationalization” even for laws that were purposefully discriminatory. Poll taxes, elaborate registration regulations, and early poll closings were all designed to limit who could vote but were defended as ways to prevent fraud and corruption, even when there was no evidence that fraud or corruption was a problem. Kagan noted that the Arizona law permitting the state to throw out ballots cast in the wrong precinct invalidated twice as many ballots cast by Indigenous Americans, Black Americans, and Hispanic Americans as by whites.

“The majority’s opinion mostly inhabits a law-free zone,” she wrote.

Congress has been slow to protect voting rights. Although it renewed the Voting Rights Act by an overwhelming majority in 2006, that impulse has disappeared. In March 2021, the House of Representatives passed the For the People Act on which Representative Lewis had worked, a sweeping measure that protects the right to vote, removes dark money from politics, and ends partisan gerrymandering. Republicans in the Senate killed the bill, and Democrats were unwilling to break the filibuster to pass it alone.

An attempt simply to restore the provision of the Voting Rights Act gutted in 2013 has not yet been introduced, although it has been named: the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act. Only one Republican, Alaska senator Lisa Murkowski, has signed on to the bill. Yesterday, the chair of the Congressional Black Caucus, Representative Joyce Beatty (D-OH), was arrested with eight other protesters in the Hart Senate Office Building for demanding legislation to protect voting rights.

After her arrest, Beatty tweeted: “You can arrest me. You can’t stop me. You can’t silence me.”

Last June, Representative Lewis told Washington Post columnist Jonathan Capehart that he was “inspired” by last summer’s peaceful protests in America and around the world against police violence. “It was so moving and so gratifying to see people from all over America and all over the world saying through their action, ‘I can do something. I can say something,’” Lewis told Capehart. “And they said something by marching and by speaking up and speaking out.”

Capehart asked Lewis “what he would say to people who feel as though they have already been giving it their all but nothing seems to change.” Lewis answered: “You must be able and prepared to give until you cannot give any more. We must use our time and our space on this little planet that we call Earth to make a lasting contribution, to leave it a little better than we found it, and now that need is greater than ever before.”

“Do not get lost in a sea of despair,” Lewis tweeted almost exactly a year before his death. “Do not become bitter or hostile. Be hopeful, be optimistic. Never, ever be afraid to make some noise and get in good trouble, necessary trouble. We will find a way to make a way out of no way.”