Reviewing Tom Stoppard A Life was an interesting process – looming large was the question ‘How did I enjoy the plays of this conservative person who, in my opinion, dined too many times with Margaret Thatcher? The closest I could come to recalling any sense of political unease was at the end of seeing Night and Day. Travesties was the first of Stoppard’s plays that I saw, and loved it. I found The Real Thing poignant, rather than something to gnash my teeth at. And after finishing the biography I wanted to see the plays again, and add a few more to my list of Stoppard plays to be seen. On a lighter note, the second book reviewed, the stories and drawings by Emily Carr in Unvarnished are full of fun, and some good politics as well.

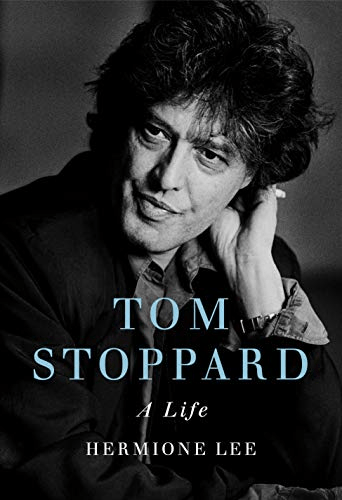

Hermione Lee Tom Stoppard A Life Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 23 Feb 2021.

Tom Stoppard A Life is an immense book – in concept, execution, and size. In case the last detail is daunting, Hermione Lee has used every bit of content, each word, the descriptions and observations with meticulous intent and elegance. Stoppard’s childhood, leaving behind the Nazi threat, escape to Singapore and early life in India, then to England which became a beloved haven and home; his family relationships, friendships and marriages; conservative politics, so often at odds with friends, partners and this reviewer; the peripatetic life following production of his plays; his plethora of other writing; and – so much joy here – descriptions of so many of the plays, the backgrounds, the rewriting, the highs and the lows. Books: Reviews

Kathryn Bridge ed. Unvarnished by Emily Carr Royal BC Museum 2021.

Kathryn Bridge has brought Emily Carr’s delightful drawings and prose to a wider audience than the papers from which they have been culled would have been able to do. Bridge has been meticulous in drawing attention to the significance of the works, in explaining the background to some of the awkwardness in the prose and providing an important context. She also provides an excellent explanation for her approach to transcribing the work. As an academic approach to her book, none of this can be faulted.

However, there is a distinct difference between the biographical and explanatory material and the beautiful and deceptive simplicity of Emily Carr’s work. The interwoven nature of Bridge’s explanatory and bridging material between examples of Carr’s writing is valuable and provides a biography that relies not only on Carr’s work, but knowledge of her circumstances and the context. However, the disadvantage of this approach is that it unfortunately highlights the difference between the deftness of Carr’s prose and illustrations and Bridge’s information. While the academic standard Bridge has achieved is exemplary, I feel the book would have benefitted from a lighter touch and more engaging presentation of the biographical material. Books: Reviews

Articles after the Covid report are related to Ukraine and International Women’s Day: Past American President’s observations on Putin; Heather Cox Richardson and Anne Applebaum write about Ukraine and the Russian invasion; IWD and CEDAW, Jocelynne Scutt; NFSA IWD films; UN Women Australia event; Ketanji Brown Jackson.

Covid since lockdown ended in Canberra

Student returns and O Week lead to a spike in numbers

With the return of students to ANU and orientation activities the number of Covid infections has risen, including amongst more than 200 students who were recorded on the 23rd. Students are now in self- solation at ANU facilities or their homes. On the 25th Canberra recorded 773 new cases, but on the positive side, boosters hit a milestone, so that two thirds of the eligible Canberra population has received their third dose. There are now more than 600 cases at ANU. Fourteen people are in hospital, three in ICU but none are ventilated.

On 26th February the following statistics for vaccination were recorded: Five to eleven year olds – 78% 1 dose; over twelve – 98.6% 2 doses; over sixteen – 66.6% 3 doses. New cases recorded – 478; people in hospital – 41; in ICU – 2; and no-one is ventilated.

New cases recorded on 27th and 28th February – 495 and 464. On March 1 and 2 new cases recorded were 692 and 1,053 with 45 people in hospital on March 1, and none in ICU; and on March 2 40 in hospital and none in ICU.

The total number of lives lost to Covid since March 2020 is 34. There have been 51,244 total cases since 12 March 2020. Vaccination rates continue to increase in the Canberra community.

–

Ukraine

Copied from Twitter:

Past American Presidents’ observations:

Clinton: Brazen violation; GWB: The gravest security crisis on the European continent since World War 11; Obama: A brazen attack on the people of Ukraine, in violation of International Law; Trump: That’s pretty smart.

Heather Cox Richardson

February 26, 2022 (Saturday)

We are in what feels like a moment of paradigm shift.

On this, the third day of Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, it appears the invasion is not going the way Russian president Vladimir Putin hoped. The Russians do not control the airspace over the country, and, as of tonight, despite fierce fighting that has taken at least 198 Ukrainian lives, all major Ukrainian cities remain in Ukrainian hands. Now it appears that Russia’s plan for a quick win has made supply lines vulnerable because military planners did not anticipate needing to resupply fuel and ammunition. In a sign that Putin recognizes how unpopular this war is at home, the government is restricting access to information about it.

Russia needed to win before other countries had time to protest or organize and impose the severe economic repercussions they had threatened; the delay has given the world community time to put those repercussions into place.

Today, the U.S. and European allies announced they would block Russia’s access to its foreign currency reserves in the West, about $640 billion, essentially freezing its assets. They will also bar certain Russian banks from the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication system, known as SWIFT, which essentially means they will not be able to participate in the international financial system. Lawmakers expect these measures to wreak havoc on Russia’s economy.

The Ukrainian people have done far more than hold off Putin’s horrific attack on their country. Their refusal to permit a corrupt oligarch to take over their homeland and replace their democracy with authoritarianism has inspired the people of democracies around the world.

The colors of the Ukrainian flag are lighting up buildings across North America and Europe and musical performances are beginning with the Ukrainian anthem. Protesters are marching and holding vigils for Ukraine. The answer of the soldier on Ukraine’s Snake Island to the Russian warship when it demanded that he and his 12 compatriots lay down their weapons became instantly iconic. He answered: “Russian warship: Go f**k yourself.”

That defiance against what seemed initially to be an overwhelming military assault has given Ukraine a psychological edge over the Russians, some of whom seem bewildered at what they are doing in Ukraine. It has also offered hope that the rising authoritarianism in the world is not destined to destroy democracy, that authoritarians are not as strong as they have projected.

President Volodymyr Zelensky of Ukraine has stepped into this moment as the hero of his nation and an answer to the bullying authoritarianism that in America has lately been mistaken for strength. Zelensky was an actor, after all, and clearly understands how to perform a role, especially such a vital one as fate has thrust on him.

Zelensky is the man former president Donald Trump tried in July 2019 to bully into helping him rig the 2020 U.S. election. Then, Trump threatened to withhold the money Congress had appropriated to help Ukraine resist Russian expansion until Zelensky announced an investigation of Joe Biden’s son Hunter.

Since the invasion, Zelensky has rallied his people by fighting for Kyiv both literally and metaphorically. He is releasing videos from the streets of Kyiv alongside his government officers, and has been photographed in military garb on the streets. Offered evacuation out of the country by the U.S., he answered, “I need ammunition, not a ride.” His courage and determination have boosted the morale of those defending their country against invaders and, in turn, captured the imagination of people around the world hoping to stem the recent growth of authoritarianism, who are now making him—and Ukraine—an icon of courage and principle.

In a sign of which way the wind is blowing, today Czech president Miloš Zeman and Hungary’s prime minister Viktor Orbán, both of whom have nurtured friendly relations with Putin, came out against the invasion. Zeman called for Russia to be thrown out of SWIFT; Orbán said he would not oppose sanctions. Even Fox News Channel personality Tucker Carlson has begun to backpedal on his enthusiasm for Russia’s side in this war.

Trump lawyer Rudy Giuliani, who was part of the scheme to get Zelensky to announce an investigation of Hunter Biden, today got in on the act of defending Ukraine. He tweeted: “The Ukrainian People are fighting for freedom from tyranny. Whether you realize or not, they are fighting for you and me.” But then he continued: “And our current administration is doing the minimum to support them, even though Biden’s colossal weakness and ineptitude helped to embolden Putin to do it.”

The right-wing talking point that Biden is weak and inept and therefore emboldened Putin to invade Ukraine is belied by the united front the western world is presenting. After the former president tried to weaken NATO and even discussed withdrawing from the treaty, Biden and Secretary of State Antony Blinken have managed to strengthen the alliance again. They have brought the G7 (the seven wealthiest liberal democracies), the European Union, and other partners and allies behind extraordinary economic sanctions, acting in concert to make those sanctions much stronger than any one country could impose.

They have managed to get Germany behind stopping the certification of Nord Stream 2, the gas pipeline from Russia to Germany that would have tied Europe more closely to Russia, and in what Marcel Dirsus, a German political scientist and fellow at the Institute for Security Policy at Kiel University, told the Washington Post was possibly “one of the biggest shifts in German foreign policy since World War II,” Germany is now sending weapons to Ukraine and has agreed to impose economic sanctions.

Biden has facilitated this extraordinary international cooperation quietly, letting European leaders take credit for the measures his own administration has advocated. It is a major shift from the U.S.’s previous periods of unilateralism and militarism, and appears to be far more effective.

Asked tonight what he would do differently than Biden in Ukraine, former president Trump answered: “Well, I tell you what, I would do things, but the last thing I want to do is say it right now.”

For all the changes in the air, there is still a long way to go to restore democracy.

There is also a long way to go to restore Ukraine. Tonight the Russians are storming Kyiv.

Anne Applebaum

The article below was first published in The Atlantic FEBRUARY 24, 2022:

Calamity Again

No nation is forced to repeat its past. But something familiar is taking place in Ukraine.

Dear God, calamity again!

It was so peaceful, so serene;

We had just begun to break the chains

That bind our folk in slavery

When halt! Once again the people’s blood

Is streaming …

The poem is called “Calamity Again.” The original version was written in Ukrainian, in 1859, and the author, Taras Shevchenko, was not speaking metaphorically when he wrote about slavery. Shevchenko was born into a family of serfs—slaves—on an estate in what is now central Ukraine, in what was then the Russian empire. Taken away from his family as a child, he followed his master to St. Petersburg, where he was trained as a painter and also began to write poetry. Impressed by his talent, a group of other artists and writers there helped him purchase his freedom.

By the time Shevchenko wrote “Calamity Again,” he was universally recognized as Ukraine’s most prominent poet. He was known as Kobzar or “The Minstrel”—the name taken from his first collection of poems, published in 1840—and his words defined the particular set of memories and emotions that we would now describe as Ukraine’s “national identity.” His language and style are not contemporary. Nevertheless, it seems suddenly important to introduce this 19th-century poet to readers outside Ukraine, because it seems suddenly important to make this same set of memories and emotions tangible to an audience that isn’t going to read Shevchenko’s romantic ballads. So much has been written about Russian views of Ukraine; so many have speculated about Russian goals in Ukraine. The president of Russia on Monday even informed us, in an hour-long rant, that he thinks Ukraine shouldn’t exist at all. But what does Ukraine mean to Ukrainians?

Read our ongoing coverage of the Russian invasion in Ukraine

The Ukrainians emerged from the medieval state of Kyivan Rus’—the same state from which the Russians and Belarusians also emerged—eventually to become, like the Irish or the Slovaks, a land-based colony of other empires. In the 16th and 17th centuries, Ukrainian noblemen learned to speak Polish and participated in Polish-court life; later some Ukrainians strived to become part of the Russian-speaking world, learning Russian and aspiring to positions of power first in the Russian empire, then in the Soviet Union.

Yet during those same centuries, a sense of Ukrainianness developed too, linked to the peasantry, serfs, and farmers who would not or could not assimilate. The Ukrainian language, as well as Ukrainian art and music, were all preserved in the countryside, even though the cities spoke Polish or Russian. To say “I am Ukrainian” was, once upon a time, a statement about status and social position as well as ethnicity. “I am Ukrainian” meant you were deliberately defining yourself against the nobility, against the ruling class, against the merchant class, against the urbanites. Later on, it could mean you were defining yourself against the Soviet Union: Ukrainian partisans fought against the Red Army in 1918 and then again in the dying days of the Second World War and the early years of the Cold War. The Ukrainian identity was anti-elitist before anyone used the expression anti-elitist, often angry and anarchic, occasionally violent. Some of Shevchenko’s poetry is very angry and very violent indeed.

Because it could not be expressed through state institutions, Ukrainian patriotism was, like Italian or German patriotism in the same era, expressed in the 19th century through voluntary, religious, and charitable organizations, early examples of what we now call “civil society”: self-help and study groups that published periodicals and newspapers, founded schools and Sunday schools, promoted literacy among the peasants. As they gained strength and numbers, Moscow came to see these grassroots Ukrainian organizations as a threat to the unity of imperial Russia. In 1863 and then again in 1876, the empire banned Ukrainian books and persecuted Ukrainians who wrote and published them. Shevchenko himself spent years in exile.

Still, Ukrainianness survived in the villages and grew stronger among intellectuals and writers, remaining powerful enough to persuade Ukrainians to make their first bid for statehood at the time of the Bolshevik revolution in 1917. Though they lost that chance in the ensuing civil war, the Bolsheviks immediately realized that Ukraine should have its own republic within the Soviet Union, run by Ukrainian Communists. Ukrainian mistrust of authority, especially Soviet authority, remained. When Stalin began the forcible collectivization of agriculture all across the Soviet Union in 1929, a series of rebellions broke out in Ukraine. Stalin, like the Russian imperial aristocracy before him, began to fear that he would, as he put it, “lose” Ukraine: Even Ukrainian Communists, he feared, did not want to obey his orders. Soon afterward, Soviet secret policemen organized teams of activists to go from house to house in parts of rural Ukraine, confiscating food. Some 4 million Ukrainians died in the famine that followed. Mass arrests of Ukrainian intellectuals, writers, linguists, museum curators, poets, and painters followed.

There are no simple lines to be drawn between the past and the present. There are no direct analogies; no nation is forced to repeat its past. But the experiences of our parents and grandparents, the habits and lessons they taught us, do shape the way we see the world, and it is perhaps not an accident that in the late 20th century, Stalin’s greatest fear came to pass and the Ukrainians once again organized, this time successfully, a grassroots civic movement that won independence from the Soviet Union in 1991. Nor, perhaps, is it an accident that many Ukrainians remained wary of the state, even of their own state, in the ensuing years. Because the state—the government, the rulers, the “power”—had always been “them,” not “us,” there was no tradition of Ukrainian civil service or military service; there was no tradition of public service at all. If the cancer of corruption, which afflicted all of the weary, cynical, exhausted republics formed in the wreckage of the Soviet Union, was particularly virulent in Ukraine, this is a part of the explanation.

But, in the long tradition of their parents and grandparents, millions of Ukrainians did continue to resist both corruption and autocracy. And precisely because it was opposed to the post-Soviet kleptocracy, Ukrainianness in the 21st century became intertwined with aspirations for democracy, for freedom, for rule of law, for integration in Europe. By the beginning of the 21st century, Ukrainians began to object to the post-Soviet establishment, linked by financial interests to Russia, and began once again agitating for something more fair and more just.

Franklin Foer: It’s not ‘The’ Ukraine

Twice, in 2005 and 2014, self-organized Ukrainian street movements toppled kleptocratic, autocratic leaders who, backed by Russia, had tried to steal Ukrainian elections and override the rule of law. In 2005, Russia responded with a renewed effort to interfere in Ukrainian politics. In 2014, Russia responded with the invasion of Crimea and multiple assaults on eastern-Ukrainian cities. The only attacks that succeeded were in the far east, in Donbas, because the Russian-created “separatist” movement could be backed up by the Russian army.

But Ukraine’s character remained unchanged. In 2019, 70 percent of Ukrainians once again voted against the establishment. A total outsider became president: a Jewish actor born in eastern Ukraine with no political experience but a long history of making fun of those who are in power—the kind of humor that Ukrainians value the most. Volodymyr Zelensky was famous for playing a downtrodden schoolteacher who rants against corruption and is filmed by a student. In the television series, the clip goes viral, the teacher accidentally wins the presidency, and then everyone—his unpleasant boss, his unsympathetic family, rich strangers—is suddenly sycophantic. Zelensky the actor makes fun of them, outsmarts them. Ukrainians wanted Zelensky the real-life president to do the same.

During his election campaign, Zelensky also promised to end the war with Russia, the ongoing, debilitating conflict along the border of eastern Ukraine that has taken more than 14,000 lives in the past decade. Many Ukrainians hoped he would achieve that too. He did seek to establish links to the inhabitants of occupied Crimea and Donbas; he asked for meetings with the Russian president, Vladimir Putin; meanwhile, he kept seeking Ukrainian integration with the West.

And then, calamity again.

It was so peaceful, so serene;

We had just began to break the chains

That bind our folk in slavery

When halt! Once again the people’s blood

Is streaming …

Ukraine is now under brutal attack, with tens of thousands of Russian troops moving through its eastern provinces, along its northern border and its southern coast. For like the Russian czars before him—like Stalin, like Lenin—Putin also perceives Ukrainianness as a threat. Not a military threat, but an ideological threat. Ukraine’s determination to become a democracy is a genuine challenge to Putin’s nostalgic, imperial political project: the creation of an autocratic kleptocracy, in which he is all-powerful, within something approximating the old Soviet empire. Ukraine undermines this project just by existing as an independent state. By striving for something better, for freedom and prosperity, Ukraine becomes a dangerous rival. For if Ukraine were to succeed in its decades-long push for democracy, the rule of law, and European integration, then Russians might ask: Why not us?

I am not romantic about Zelensky, nor am I under any illusions about Ukraine, a nation of 40 million people, among them the same percentages of good and bad people, brave and cowardly people, as anywhere else. But at this moment in history, something unusual is happening there. Among those 40 million, a significant number—at all levels of society, all across the country, in every field of endeavor—aspire to create a fairer, freer, more prosperous country than any they have inhabited in the past. Among them are people willing to dedicate their lives to fighting corruption, to deepening democracy, to remain sovereign and free. Some of those people are willing to die for these ideas.

The clash that is coming will matter to all of us, in ways that we can’t yet fathom. In the centuries-long struggle between autocracy and democracy, between dictatorship and freedom, Ukraine is now the front line—and our front line too.

Anne Applebaum is a staff writer at The Atlantic, a fellow at the SNF Agora Institute at Johns Hopkins University, and the author of Twilight of Democracy: The Seductive Lure of Authoritarianism.

International Women’s Day

Cambridge Guild Hall Council Chamber – Women’s Parliament … International Women’s Day 8 March 2022 … 25 spectacular women debate a Motion for a Women’s Bill of Rights … Women’s Rights Today – ‘if not now, when!’ https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCQXsMUvfbeuJZbRah_NV_uA (activate 10am Tuesday 8 March 2022 … 10-1pm Women’s Parliament)

Ian Rothwell A Bit of Everything, Salford City Radio

This Tuesday we welcome back the Hon Dr Jocelynne Scutt AO President of the CEDAW People’s Tribunal. In the run up to International Women’s Day on 8th Jocelynne will be informing us about the Women’s Parliament & the Convention on the Elimination of All forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) & associated issues. Also 1950’s Women talk about how the rise in the State Pension has affected them. Plus music from Stace Cohen, Keelin Rose & Charm of Finches. Join us just after 6pm.

This year for International Women’s Day, for the entire month Arc Cinema will focus on films by women and women’s contributions to cinema.

NFSA Arc Cinema International Women’s Day March Program

Beginning this month is the first episode of Mark Cousins’ epic 14-part series Women Make Film (2018), accompanied by Samira Makhmalbaf’s Blackboards (2000) on 35mm film.

CANBERRA SCREENINGS AND EVENTS

BY MATT KEMP (edited)

Autumn has arrived and brings a spectacular line-up of films this March at Arc Cinema!

This year for International Women’s Day, for the entire month Arc Cinema will focus on films by women and women’s contributions to cinema. Beginning this month is the first episode of Mark Cousins’ epic 14-part series Women Make Film (2018), accompanied by Samira Makhmalbaf’s Blackboards (2000) on 35mm film.

To celebrate our Australians & Hollywood exhibition, join us for a selection of films that helped catapult some of Australia’s finest female actors into Hollywood stardom. Throughout the month, we’ll be showing Margot Robbie as Tonya Harding in I, Tonya (2017), Toni Collette as a concerned and protective mother in The Sixth Sense (1999), Cate Blanchett’s commanding lead role in Elizabeth (1998), Naomi Watts’ heart-wrenching performance in 21 Grams (2003) and Nicole Kidman as a scheming weather reporter in To Die For (1995).

The Films That Made Them Famous: I, Tonya – 4 March, 7pm

The Films That Made Them Famous: The Sixth Sense – 5 March, 6pm

Arc Out Loud: Tank Girl – 11 March, 8pm

The Films That Made Them Famous: Elizabeth – 25 March, 7pm

The Films That Made Them Famous: 21 Grams – 26 March, 2pm

The Films That Made Them Famous: To Die For – 26 March, 6pm

» Full line-up here

Canberra IWD celebrations

UN Women Australia will be celebrating under the IWD theme, Changing Climates: Equality today for a sustainable tomorrow – recognising the contribution of women and girls around the world, who are working to change the climate of gender equality and build a sustainable future.

Date: 11.30am-3pm, 4 March

Location: National Convention Centre & online

Registration: Humanitix

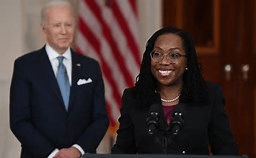

President Biden’s Supreme Court Judge nomination – Ketanje Brown Jackson

Article from The White House (edited)

Since Justice Stephen Breyer announced his retirement, President Biden has conducted a rigorous process to identify his replacement. President Biden sought a candidate with exceptional credentials, unimpeachable character, and unwavering dedication to the rule of law. And the President sought an individual who is committed to equal justice under the law and who understands the profound impact that the Supreme Court’s decisions have on the lives of the American people.

That is why the President nominated Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson to serve as the next Justice on the Supreme Court. Judge Jackson is one of our nation’s brightest legal minds and has an unusual breadth of experience in our legal system, giving her the perspective to be an exceptional Justice.

About Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson

Judge Jackson was born in Washington, DC and grew up in Miami, Florida. Her parents attended segregated primary schools, then attended historically black colleges and universities. Both started their careers as public school teachers and became leaders and administrators in the Miami-Dade Public School System. When Judge Jackson was in preschool, her father attended law school. In a 2017 lecture, Judge Jackson traced her love of the law back to sitting next to her father in their apartment as he tackled his law school homework—reading cases and preparing for Socratic questioning—while she undertook her preschool homework—coloring books.

Judge Jackson stood out as a high achiever throughout her childhood. She was a speech and debate star who was elected “mayor” of Palmetto Junior High and student body president of Miami Palmetto Senior High School. But like many Black women, Judge Jackson still faced naysayers. When Judge Jackson told her high school guidance counselor she wanted to attend Harvard, the guidance counselor warned that Judge Jackson should not set her “sights so high.”

That did not stop Judge Jackson. She graduated magna cum laude from Harvard University, then attended Harvard Law School, where she graduated cum laude and was an editor of the Harvard Law Review.

Judge Jackson lives with her husband, Patrick, and their two daughters, in Washington, DC.

Experience

Judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit

Judge on the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia

Vice Chair of the U.S. Sentencing Commission

Public defender

Supreme Court Clerk

The White House

1600 Pennsylvania Ave NW

Washington, DC 20500

The Lincoln Project

For the first time ever, a female Vice President, Kamala Harris, and a female Speaker of the House, Nancy Pelosi, sat behind the President for the #SOTU address.

Tonight, history was made on the first evening of #WomensHistoryMonth.