This week, the review of a book about spinsterhood in which it is claimed that there are few positive images of spinsters in fiction, moved me to write about the spinsters that are an important part of Barbara Pym’s fiction. Pym gave a positive, often comic, and sometimes trenchant, voice to the spinsters in her novels written between the 1930s and 1980.

A Few Green Leaves: Barbara Pym’s Last Word on Spinsterhood

Barbara Pym’s affection for the spinsters with which she generously peopled her six published novels is undiminished in her last, A Few Green Leaves. Although a relatively young woman is the central character, she is of an age when there is an expectation that she might marry. However, a romantic story line does not override the depiction of spinsters in all age groups. Any romantic notions of coupledom are undermined by happy spinsterhood, the fraught nature of marriage as demonstrated by the couples, together with a satisfied widow with a wry outlook on marriage. That single women are an unhappy group, seeking marriage or remarriage is severely undercut by Pym’s depiction of their comfortable lives, juxtaposed with the less happy ones of their married sisters. Pym wrote about spinsters from her early writing in the 1920s to a final celebration of the unmarried state in A Few Green Leaves, published posthumously in 1980. Her attention to spinsterhood is at odds with the argument made in the book recently published and reviewed below. This rewriting of women’s fictional history is not unique; it certainly draws attention to a facet of women’s writing that deserves to be recognised. However, it is also worth giving Barbara Pym’s early recognition of the positives of spinsterhood their due. For the complete review see Books: Reviews

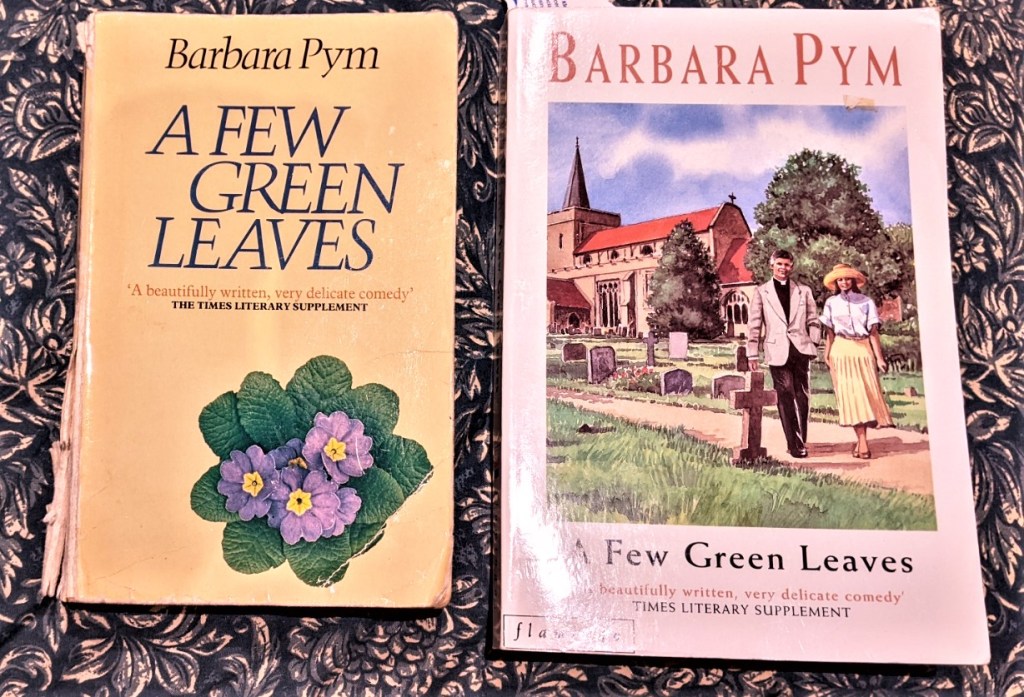

Cover, A Few Green Leaves, Granada 1981.

Cover, A Few Green Leaves, Flamingo 1994.

This is an interesting contrast in the priorities established by the publishers. The later cover suggests a possible romantic alliance between two of the characters. The earlier cover reflects the suggestion that a few green leaves can make an important difference: a Pym suggestion in the text.

How a new wave of literature is reclaiming spinsterhood

The unmarried woman has long been derided in popular culture and beyond. Now single women are telling their side of the story.

This week the review of She I Dare Not Name: A Spinster’s Meditations on Life by Donna Ward, Allen & Unwin, 2022, a book about spinsterhood in which it is claimed that there are few positive images of spinsters in fiction, moved me to write about the spinsters to whom Barbara Pym gave a positive and sometimes comic voice in her novels written between the 1930s and 1980.

How a new wave of literature is reclaiming spinsterhood

By Emma John

In 1869, the essayist William Rathbone Greg published a 40-page treatise on the worrying trend of the “surplus” – aka unmarried – woman. Under the title “Why Are Women Redundant?” Rathbone regretted these tragic figures who, rather than “sweetening and embellishing the existence of others”, were forced to lead lives both independent and “incomplete”. Greg, along with many other Victorians, was alarmed by the census data: 1.8 million single women in 1851 had been bad enough, but a decade later the figure had grown to 2.5 million. And it wasn’t just men who were concerned. In an essay asking “What Shall We Do With Our Old Maids?”, the reformer Frances Power Cobbe advised that “one in four women are certain not to marry” and advocated for increased education and employment. Reformers and traditionalists both backed emigration policies that would send these “excess women” overseas to work (or marry) in British colonies. See the full review in Further Commentary and Articles about Authors and Books*

Articles and commentary after Covid in Canberra: Showing at the NGA; Leoni Norrington and Barrumbi Kids; Tony Blair and Michael Sheen Interview; Bob McMullan – The key lessons from the South Australian election (Women’s Election?).

Covid in Canberra

On 31 March there were 1,194 new cases recorded, with 47 in hospital, three in ICU and one ventilated. 98.1% of the Canberra population over five have received two doses of the vaccine. There were 1, 014 new cases recorded on 1 April. New cases dropped on 2 April, to 808. On 3 April there were 718 new cases.

On April 4 Canberra recorded 739 cases, a drop in numbers of cases. However, the numbers in ICU have increased in a five day peak , to four in ICU and two on ventilation. The previous figure of five in ICU was recorded on March 30. Three people died in the ACT from Covid last week, bringing the death toll to forty two. Figures by age group for new daily infections recorded on 4 April are: 0-4: 45(6%); 5- 11.44 (6%); 12-17:82 (11%); 18-24:64 (9%); 25 – 39:215 (29%); 40- 49:124 (14%); 50-64:101(14%); 65+:64 (9%).

New numbers for 5 April showed another increase as there were 918 new cases recorded. There were forty one people in hospital, with five in ICU and two ventilated. Another life was lost to Covid. On 6 April there was another increase in the number of new recorded cases – 1,149. Forty two people are in hospital, with four in ICU, two of whom are ventilated.

Showing at the National Gallery of Australia

Darwin author Leonie Norrington’s book series The Barrumbi Kids to become TV show

By Eleni Roussos and Dianne King

Posted 11h ago11 hours ago, updated 3h ago3 hours ago

Northern Territory author Leonie Norrington has some simple advice for budding writers: look to your own life and share it.

“Use your own experience, your own landscape, your own people to feed your work,” she said.

“That’s the essential part of you and the essential part of where you come from.”

The author has done just that, turning her childhood memories of growing up in an Aboriginal community in the Northern Territory into books for children.

Her most popular series The Barrumbi Kids was published in 2002, and follows a group of friends who learn about themselves through hunting and fishing in the bush.

Two decades on, her books are about to reach a new audience on the small screen, with National Indigenous Television (NITV) commissioning The Barrumbi Kids to be turned into a TV show in 2022.

The author travelled to Beswick south-east of Katherine for the filming and hopes the “wonderful relationship between black people and white people” comes across on screen.

“So often the information that comes out of communities is negative and it’s not all negative at all, there’s such joy,” she said.

Being on set was art imitating life for the 65-year-old author, who spent the early years of her life living on the same Jawoyn country where the TV show was filmed.

The third of nine children, Norrington credits her childhood spent in the tiny community of Barunga in the 1960s for having the “biggest influence” on her career.

She said finding ways to celebrate “the difference but sameness between cultures” had been the cornerstone of her work as a writer.

“It was a really unique way to grow up, growing up in the bush with people who were living mostly a traditional way with their customs and hunting all the time,” she said.

“All of us children just ran around the bush with them; it was a really wonderful, exciting life.”

The Darwin author says feeling “like the minority” in the community had had a profound impact on her work as a writer.

“There weren’t that many white people who looked like me on the community,” she said.

“I think that’s a really valuable thing as a writer to always know that you don’t know, to always be on the outside somehow.”

It was the birth of her first grandson on the other end of the country that inspired the former ABC Gardening Australia presenter to start writing books for children.

“I wanted him to know what it was like to live in the territory,” she said.

“I want stories for our kids, stories that legitimate who we are as a people.”

Norrington has finished her doctorate in literature, writing her first adult novel set in Blue Mud Bay in Arnhem Land in pre-colonial times.

She said she was inspired to write the novel by her late ‘Aboriginal mother’ Clair Bush, a Yolngu woman who took her under her wing when she was a child.

“It was a serious adoption, she looked after us…she’s the one who taught us and the one I’ve written under her supervision all these years,” she said.

“Her mission was to have remote Aboriginal people shown as really powerful strong characters.”

Norrington credits Ms Bush as being the powerhouse behind the success of The Barrumbi Kids, and said she would have been proud to see the stories from Barunga make national television.

“I hope people love it, I hope people identify with the kids and I hope that the Aboriginal characters come across as really powerful and strong in their own right,” she said.

This story is part of a special Born and Bred series, celebrating the work of remarkable Territorians.

From: The New Statesman

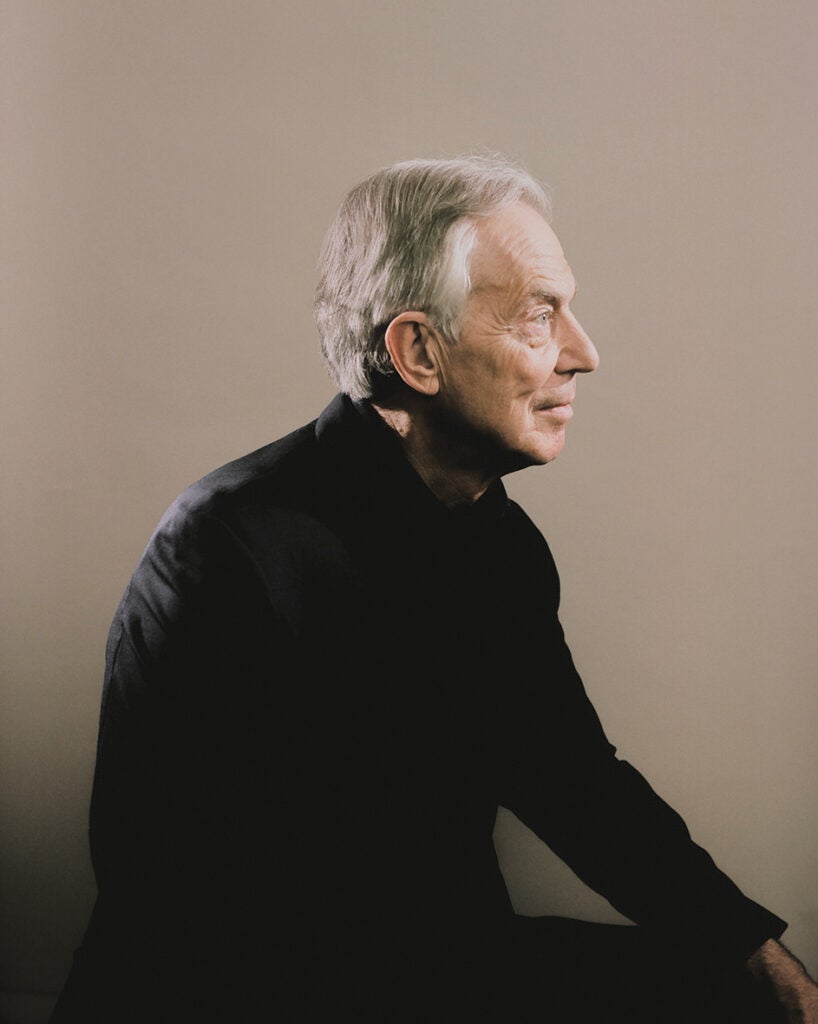

“I tried to give Britain a different narrative”: Tony Blair and Michael Sheen in conversation

The former prime minister and the actor who played him talk “wokeness”, national identity, and what Blair has in common with Jeremy Corbyn.

By Michael Sheen and Tony Blair

On a Sunday afternoon in mid-February, Michael Sheen and Tony Blair laughed when they first saw one another on Zoom. They are two very different national figures, but their careers are nevertheless entwined, the actor having played the former prime minister three times – most notably opposite Helen Mirren’s Elizabeth II in the 2006 biopic The Queen.

Sheen no longer looked eerily like Blair. Dialling in from Glasgow, where he was filming a new series of Neil Gaiman’s Good Omens, his thick curls had been replaced by a short shock of peroxide blond. Blair, in turn, had cut the long hair he grew during the pandemic, described in the British press as his “lockdown mullet”.

“You look younger,” Blair said. “My lockdown hairstyle was much commented on –but not that I looked younger.”

They had met to talk about the meaning of Britain, which has changed greatly since Blair left office in 2007, and since Sheen last played him in the 2010 television film The Special Relationship (opposite Dennis Quaid as Bill Clinton). During the tumultuous decade since its release, a succession of Conservative-led governments have shrunk the state after the largesse and renewal of the New Labour years. The UK has left the European Union, its identity now split between Little Englander neurosis and Global Britain fantasy – a messy rejection of the globalisation synonymous with Blairism. With the creation of an Irish Sea border, and a Brexit-sceptic Scotland, the Union itself is under threat.

Speaking a week before Russia invaded Ukraine, the two men discussed what a “British Dream” should be, the future of the Labour Party, and the UK’s changing role in the world – questions that have become more urgent since the outbreak of war.https://embed.acast.com/6b2fc9ba-b9b7-4b7a-b980-e0024facd926/6239fd043414c10012eb920c?bgColor=faf6f4&font-family=Helvetica%20Neue&font-src=Helvetica%20Neue&logo=false&secondaryColor=d82d1d

Representing different traditions of the left, Sheen and Blair clashed over what went wrong for Jeremy Corbyn and how Labour can win again, but agreed on one fundamental challenge: watching oneself on screen.

Introduced and chaired by Anoosh Chakelian, the NS Britain editor

Michael Sheen I have a lot of cognitive dissonance when it comes to you, because it’s like seeing a family member or something. I remember Stephen Frears, who directed two of the films where I played you, said “Don’t ever forget that these are the smartest people in the room, always.”

Tony Blair That was generous, if inaccurate.

MS When we were making The Queen, it seemed as if [by the time of New Labour] the story Britain told about itself had changed. The Britain you grew up in, were educated in, became a barrister in, got into politics in – what was that Britain telling the world about who it was, and why did you come to think that story needed to change?

TB Britain finds it very difficult to tell a story about itself, because there is a narrative that supposes our best days are behind us, and that’s caught up in what happened in the Second World War: Churchill defeated Nazism, Britain’s finest hour.

My idea was to take what I think are the enduring best qualities of Britain – open-mindedness, tolerance, innovation – and try to give Britain a different narrative that would allow it to think its best days are ahead of it. I think, for a time, that succeeded, and it probably culminated in winning the Olympic bid in 2005. We quite deliberately put Britain forward as a multicultural, tolerant society, looking to the future, and I think that’s why we won that bid. And then the Olympics, when it came about in 2012, was in many ways a celebration of that.

But there have always been these two competing ideas and, bluntly, I think that over the past few years, the older narrative has reasserted itself. You only have a concept like the American Dream – and Xi Jinping now talks about a Chinese Dream – when you think your best days are ahead of you.

MS After the war, with that 1945 government and the huge changes made to the country, when did people start looking back?

TB At the end of the 19th century, we were the most powerful country in the world. The Second World War demonstrated the capacity of Britain still to play a leading role on the world stage. But from then on, you were relinquishing the trappings of empire and power.

People on the left will baulk at what I’m about to say, but in some ways, with Margaret Thatcher, there was at least the strong direction recovered. And then with New Labour, that was a progressive attempt to say: we’ve got a strong relationship with Europe, we’ve got a strong alliance with America, we’re globally significant, we’re modernising our country, we can become a centre of innovation, technology for the future. It’s still possible for us to do all of that, but in the past few years there has been something of a crisis of identity for the country.

MS How much did that weigh on you as prime minister, the country having once been the most powerful force in the world, and holding on to that influence?

TB It weighs on you for two reasons: first because of the richness of your history, but also because if countries today want to succeed, they need direction. One of the biggest problems we have right now in Britain is we don’t have a plan for our future. We’ve got three revolutions – Brexit, climate and technology – and we’re not really planning for any of them.

Countries need a sense of direction, and they need to find their place in the world. What is the role of Britain today? This is something that you have to define, some sense of the dream of the future, because that means nothing unless it’s definable.

I think you could have a British Dream, but it requires you to understand what you can offer the world today. And I think it is about being an open-minded, tolerant, innovative country and society, because that’s where we, throughout our history, have always been when we’re at our best.

Britain’s place in the world

MS Britain’s relationship with the US and Europe has changed since you were in power. How does that affect British influence? Part of going into Iraq was to stand with America.

TB We don’t have those two relationships in the same way, and as a result, we’re less influential. It’s clear. In my time, and under John Major, Margaret Thatcher, Gordon Brown, the first recipient of a call from the president of the United States would have been the British prime minister. I’m not sure that’s really true any more.

The relationship with America comes at a price, the relationship with Europe comes at a price. I never pretended that the European Union was perfect or that it was always easy-going. It wasn’t. It was very hard a lot of the time. But the relationship mattered to how we looked at ourselves and our place in the world and our ability to influence things, and therefore, when you undermine that in such a fundamental way, it’s difficult.

You can’t escape these choices. If you’re constantly indulging the view that there is a past you can recapture – which is an easy thing to do, a very simple populist message that may be politically successful in certain contexts – it doesn’t offer anything for the future.

MS It seems a large part of why people voted to break away from Europe, was out of some sense of wanting to go back to the past, of Britain as this buccaneering spirit, and an empire-building attitude. And yet it seems to have given up influence by leaving the EU. There’s a bizarre irony in that, isn’t there?

TB Yes. You’re in a much stronger position to deal with these countries whose economies eventually will be far larger than ours – China’s already is, India’s in time will be – from a position of partnership.

In the world that’s developing today, you’ve got three giants by the middle of this century: America and China for sure, and probably India. These will be giants taller than any other country; and then you’ll have the tall countries, populations like Indonesia, Brazil and Mexico and so on. France, Germany, Italy, Britain will all have populations of roughly 65 or 70 million. Unless you band together, you’re just going to get sat on by the giants.

The belief in better

MS The idea of aspiration was key to the New Labour vision for Britain. Why do you feel your record on social mobility has been misrepresented by the left?

TB Simply because when you look at the opportunities we gave people, they were immense: university education was expanded, Sure Start, massive investment in schools, big inner-city regeneration. When we left office, the NHS had its highest satisfaction ratings since records began.

It’s important for the left not to misrepresent the last Labour government, or play along with the idea that it was all about Iraq and nothing else, because then all you do is depress people about future prospects.

MS There is the idea that your government was the most redistributive since 1945, and that it was happening by stealth. But there was a tension between staying attractive to the kind of voters you need to get into power and trying to do what a Labour government is there to do, which is to be the party of social justice and a fairer economy. How did you cope with that tension?

TB That was, and is, the challenge. Provided it was clear Labour was in favour of successful business, happy for people to be ambitious and do well, strong on defence and law and order – because people care about those things – then, as it were, you got permission to do the side of it that was about social justice and compassion and liberal change.

I could see there was a new coalition emerging of people who were pro-free enterprise. In that sense, they had sympathy with the Thatcher concept, but at the same time they were socially liberal: they’d no time for racism or discrimination against gay people.

The working class – in the traditional sense that Labour often uses the word – had always had two bits to it, and one was fiercely aspirational. And that fiercely aspirational part was always what the Tories appealed to. My father was one of those people: brought up in a poor part of Glasgow, secretary of the Young Communists, and then later became convinced that Labour wanted to hold him back, and he wanted to succeed.

That is the great challenge always of progressive parties. But it’s not a challenge you can’t overcome, and Labour could do the same again today, if it decides to.

MS At a party conference fairly early on in your government, you said the fight was for a new vision of a Britain in which the old conflict between prosperity and social justice is banished to the history books where it belongs. Do you think it’s possible for a party that openly advocates social justice and a fairer economy to win power in a period where this is labelled as “wokeness” and smeared as something else? Some people say you were so successful electorally by fooling Britain into thinking that it wasn’t the Labour Party! Could someone openly just say, “This is what we believe in”? Is it possible for this country to vote that someone into power, and if not, what does that say about who we are?

TB You’re remembering my speeches better than I do! You can definitely say we want social justice and a fairer country, provided people think you’ve got a plan that’s sensible to get there. There’s no purpose in the Labour Party if it’s not going to create a fairer society and implement measures of social justice. The question is how.

What Labour people often tend to do is misunderstand why people are voting Tory. They’re often voting Tory because they fear Labour – not because they fear Labour is going to create a more just society, but because they fear Labour will bind them up in a whole lot of state power that won’t necessarily deliver that just society.

People say to me, “Labour got hammered at the last election.” And I say to them – I don’t mean to be rude about it – but we put forward Jeremy Corbyn as the prime minister – what do you think’s going to happen? What is it about British political history that tells you they’re going to put someone from that political position in charge of the country? Nothing!

Labour doesn’t need to apologise for wanting a more just society. On the contrary, it needs to say that this is its mission. It’s how you do that in the modern world that always trips up Labour. If you go back to the 1945 government, which created these great changes, the question is: why were they voted out in 1951? It happened because the Tories were able to argue Labour wasn’t paying attention to the aspirational side of the working-class people who were being helped by the very changes Labour was making.

If you want to achieve power, you’ve got to be much more intellectually rigorous about what your problem is. It isn’t that people think, “I can’t vote for people who want a more just society.” They’re not voting Labour because they worry that what we might do isn’t in line with what they conceive a more just society to be. Those two things are reconcilable, but only if you’re hard-headed about what the problem is.

MS I’m concerned that unions and collective action are now seen as regressive, and people I know don’t have any protections – people who come from the area I come from [Port Talbot in Wales] and who I meet every day. Part of the attraction for a lot of people of Jeremy Corbyn – even though his leadership was seen as “going back to the Seventies” – is that people need protection at work, when they’re on a zero-hours contract or working in an Amazon warehouse.

TB You’re absolutely right, that is the need. There are a lot of people who are exploited in the workplace today. You need trade unions that are forward-looking, that understand what the realities of the world are, how you best get that protection. They probably aren’t trying to play around with the politics inside the Labour Party, to be quite frank, but addressing the workplace issues that people have in a very practical way.

People used to think I was always rebuffing the trade unions. I used to try to explain that, if you want to represent the modern workforce, you’ve got to go to where they are and how they think, and be directed towards genuine workplace representation – not try to pull them into what they think ends up as a sort of quasi-political organisation.

We introduced the minimum wage. We introduced the right to be a member of a trade union. We got rid of a whole raft of Tory things that were anti-union. But what we didn’t do was everything the trade union movement was asking, which literally was to go back to the framework of the 1970s.

The psychology of the country towards the Tories and Labour is different. Towards the Tories, it’s: “I don’t particularly like them, I think they do look after the most wealthy in society. On the other hand, I know that all they’re interested in is power, and therefore, probably, they’ll try to work out what I want and try and give it to me.”

With Labour, it’s completely different. It’s only Labour that worries about whether it’s principled: the country thinks the party is principled. What the country worries about is: “Labour definitely believes these principles, and Labour’s got a huge commitment to social justice, but what’s that going to cost, exactly? Can you actually run the thing or will these principles be so important that you’ll take us in all sorts of strange directions?”

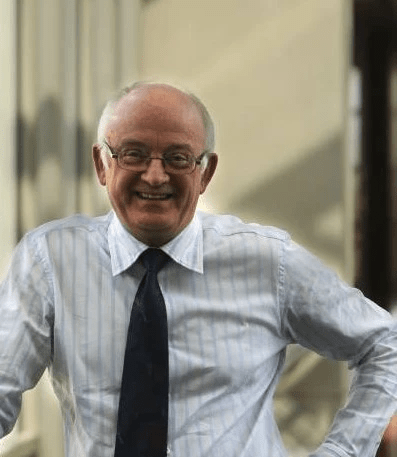

Bob McMullan

The key lessons from South Australia

The first federal election lesson I would draw from the recent South Australian election is: “the polls got it right”. This combined with the significant differential in the performance of female candidates in the election could have a profound impact on the forthcoming federal election.

We may be about to experience the women’s election.

There is much cynicism about polling. Some of it based on the recent failures of polling in Australia and USA. Some of the cynicism is based on a proper understanding of the methodological challenges facing pollsters in the 21st century, particularly given the virtual demise of landlines. However, some of the suspicion is based on ignorance and conspiracy theories.

I am as critical as most about the bias in the Murdoch press. It is now so bad it is almost laughable!

However, neither Murdoch nor Newspoll has any credible reason to deliberately distort the polling as disclosed fortnightly in The Australian. Some of the reporting in the Australian of the polling is distorted and/or just plain wrong, but the polling numbers are credible. We now have several regular polls which give Australians a chance to judge how the forthcoming election is going at the particular moment. At this relatively early stage it doesn’t necessarily tell us much about how the final result will go on election day. There is a lot of water to flow under the bridge before the result will be known.

It is however clear that the current indications are very positive for Labor and for Anthony Albanese.

A second lesson from analysis of the South Australian election results is the superior performance of female candidates.

It has been widely reported that all the key seats gained by Labor at this election were won by female candidates.

What has not been reported is the better overall performance of women as candidates at the election.

At the time of writing, although there are a few votes still to be counted, the average swing to Labor in a seat contested by a woman was 7.46%, while for male candidates the average was 6.22%.

There is no obvious explanation for this quite significant difference. It is true that several female candidates were in key marginals in which the Labor Party made extra effort, but the Liberals would also have waged major campaigns in these seats. As many of the women were running against incumbents this would suggest that the difference in gendered results may be more than suggested.

It seems the voters prefer female candidates with a margin of difference sufficient to influence the outcome in closely contested seats.

This is significant additionally because the ALP has female candidates in 18 of the 27 key seats within which the next federal election will be determined.

Taken together with the very significant number of female independents threatening otherwise safe Liberal seats, the 2022 federal election could become known as the women’s election!

In fact, to bring these two lessons together, polling suggests Labor may be very close to 50% female MPs in the lower house after this election if they do as well as the polls predict.

Applying the state-by-state polling breakdown to the pendulum suggests Labor would win 12 seats, 10 of which have female candidates for the ALP.

The ALP currently has 29 women and 38 men in the House. One new safe seat has been created, Hawke, for which a man, Sam Rae, has been selected. Of the seats of retiring members Marion Scrymgeour is running for Warren Snowdon’s seat of Lingiari and Kristina Keneally is running to replace Chris Hayes in Fowler. Assuming Andrew Charlton is chosen to contest the seat of Parramatta currently held by Julie Owens, this makes a starting point in a status quo election of 30 female and 38 males in the House for the ALP. Should Labor win the 12 seats as suggested by the current polling this would create an 80 seat ALP team in the House which would be split 40/40 between men and women.

Of course, even if the polls are correct in predicting the overall seat count it is never as precise on a seat-by seat basis. And it is far too early to be predicting how many seats Labor will win, let alone which ones it may win. But this analysis is indicative of a trend towards gender equality in the parliament as it becomes more truly a House of Representatives.

The swathe of potential Independents contesting previously safe conservative seats makes a similar analysis for the Liberals and Nationals very difficult at the moment. However, they start from a much lower base. In the current parliament the coalition has a combined gender split of 15 women /61men. If the coalition lost the same twelve seats considered above they would fall to 9/55. In addition, only 1 of the 8 men retiring at this election is being replaced by a woman. This would take a status quo election result to 16/60. A twelve-seat loss would mean 10/54.

For the purpose of comparison, should the coalition gain the first twelve seats for which they have endorsed candidates (which excludes Lilley and Greenway) they would gain five women and seven men. This would lead to a composition of the coalition House team of 21/67.

Of course, most of the members under threat from female independents are men, but losing seats is a perverse method of moving towards gender equality.

The South Australian election can predict nothing about who will win the next federal election. But it does point to some interesting underlying trends in the choices Australian voters are making. It also reinforces the point from the Western Australian election that it is unwise to disregard the message the polls are sending about public attitudes.

The prospect of a more gender balanced House, at least on the Labor side and amongst the Independents with a possible indication of voter preference for female candidates adds an intriguing note to the study of the forthcoming election.