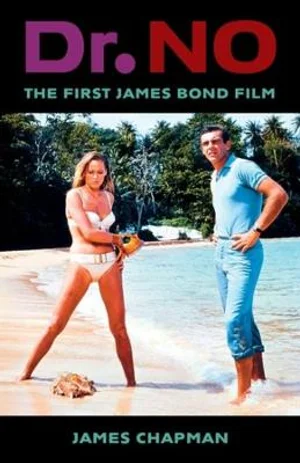

Books reviewed this week include another about film, the topic of the two books reviewed last week. Dr No was sent to me by NetGalley, in exchange for an honest review, as was the novel reviewed this week.

James Chapman Dr. No The First James Bond Film Columbia University Press, Wallflower Press Pub Date 08 Nov 2022.

When I saw Dr No available for review, I must admit that my reaction was personal, rather than an admiration for James Bond films. I saw Dr No at an Australia drive-in. By design or mistake I shall never know, my friend drove to Dr No instead of going to one where a romantic comedy or something of that ilk was playing. As I ate the drive-in fare, horrified at what I was seeing, I had no idea of the work that had brought this first James Bond film to the screen. This book has given me the opportunity to learn so much, not just about the filming of Dr No, but of the world in which a film is written, produced, and acted and directed, to arrive on the screen. It is an absolute hive of information, with some amusing stories; business and financial cases being described; analysis of script alternatives; decision making about actors, sets, and directors; reviews and analysis of the content of Dr No. Books: Reviews

Miranda Rijks What She Knew Inkubator Books, 2021

My first Miranda Rijks, and it shall not be my last. What She Knew is a satisfying read, with a title that resonates with the content, and a very smart combination of domestic drama and crime. The characters are believable, with no great potholes in their motivation and their representation. None made me wonder why they behaved as they did, each was devised to play his or her role with meticulous attention to the situation, event, or relationship.

Most importantly, the depiction of Stephanie whose marriage and the relationship between her and her husband, Oliver, is under the greatest scrutiny, delivers. The couple is first seen against a domestic background that firmly places each in a traditional role: Stephanie is attending to the children and will prepare a late supper for Oliver. Meanwhile, Oliver is going to be late as he is working. One job is associated with his profession, a professor in the History of Art Department of a university; the other is his pleasure, an online auction that is taking place in New York. Stephanie’s work is grounded in their home, with views over south London. Or so it seems.

Stephanie has a secret which she shares only with her mother. Stephanie’s attitude toward Oliver, her secret, her current role and past make for a complex interweaving of feelings and actions. What stands out is that with every episode of Stephanie’s reflection on her life her thoughts and behaviour never veer from what is feasible. Stephanie is not a character of whom one despairs, she is realistic about her past, present, and role in society. Her thoughtfulness for her husband, children and friends never grates, she is not a victim at any time in the novel, despite past traumas, reminders of these, and present dissatisfaction. Books: Reviews

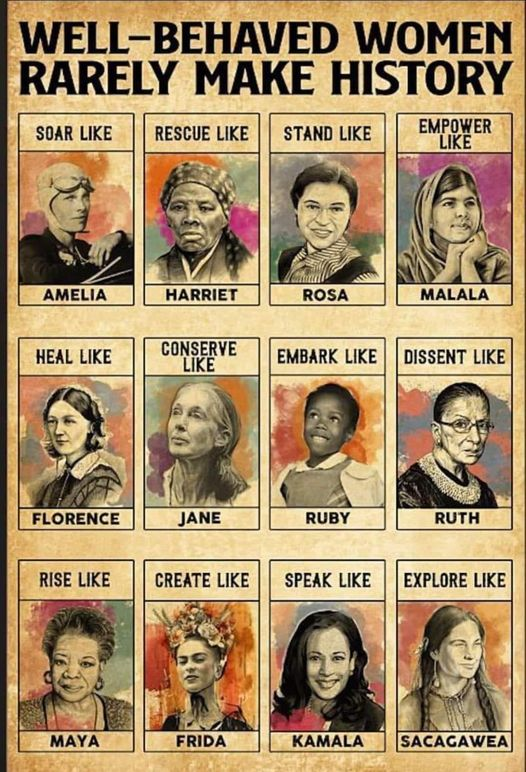

Articles and comments after the Canberra Covid information – follow up to the Dr No review, James Bond film comments; Lawrence O’Donnell Followers Facebook comment on well behaved women; ‘Hermettes’ – women choosing to be alone; Cindy Lou breakfast and a dog bowl; women directors.

Covid in Canberra after lockdown ended and after the influx of new variants

21 July – 1,407 new cases reported; 165 people in hospital; 3 people in ICU.

22 July – 891 new cases reported; 152 people in hospital; 4 people in ICU.

23 July – 1,044 new cases recorded; 145 people in hospital; and 2 people in ICU.

24 July – 712 new cases recorded; 155 people in hospital; 1 person in ICU.

25 July -790 new cases recorded; 162 people in hospital; 1 person in ICU.

26 July – 949 new cases recorded; 151 people in hospital; 1 person in ICU.

27 July – 1,104 new cases recorded; 141 people in hospital; 1 person in ICU.

Vaccination records now included better figure for ‘winter doses’ with 42.7% of people over fifty having had four doses. People over sixteen who have had 3 doses is 77.2%. More people are wearing masks at indoor shopping centres and in shops. Four people died from Covid 19 over this week.

For those readers who are interested in James bond movies beyond the review above, the following short commentary on the films might be of interest.

Every James Bond Movie Ranked From Worst to Best (Including No Time to Die)

With the release of No Time to Die, it’s time to rank the James Bond films from worst to best, from Goldfinger to Skyfall, Thunderball to Spectre.

BY KYLE WILSON PUBLISHED ONLINE OCT 02, 2021

After a long delay James Bond is back in No Time to Die, so there’s no time like the present to rank his cinematic outings from worst to best. Through six Bond actors, 60 years and 25 movies, Ian Fleming’s “blunt instrument” has punched, quipped, and slept his way through a wide variety of adventures in one of the highest-grossing media franchises of all time. Blaring horns, smoking guns, and martinis (shaken, not stirred) have woven themselves into the fabric of cinematic iconography, with the promise “James Bond will return” a constant for multiple generations.

SCREENRANT VIDEO OF THE DAY

The character first appeared in Fleming’s 1953 novel, Casino Royale, which became a hot property for radio and television adaptations. Less than a decade and exactly nine Fleming novels later, Eon Productions (owned by Harry Saltzman and Albert R. “Cubby” Broccoli), acquired the rights to 007 and released the first film in the series, Dr. No. From the moment Sean Connery introduced himself as “Bond, James Bond,” a legend was born, and the Scottish actor would go on to reprise the role in five entries before launching the tradition of passing the torch to the next 007. George Lazenby, Roger Moore, Timothy Dalton, Pierce Brosnan, and Daniel Craig have all followed, each giving their own spin on the British secret agent. See the edited article at Further Commentary and Articles about Authors and Books*

An excellent contribution to the audience of Lawrence O’Donnell’s Last Word site on Facebook.

An interesting article appears below – but I wonder whether a fairly normal (in my opinion) desire to have space, and ‘alone’ time needs an organised approach? The article raises some interesting issues as well as provoking my query.

A secret society of ‘Hermettes’ is reclaiming and celebrating female aloneness ABC RN

By Nick Baker and Julian Morrow for Sunday Extra

Posted Mon 11 Jul 2022 at 5:00amMonday 11 Jul 2022 at 5:00am, updated Mon 11 Jul 2022 at 6:07amMonday 11 Jul 2022 at 6:07am

Risa Mickenberg lives in a stylish New York City apartment, but she prefers to call the dwelling something else: Her “cave”.

Despite being in close proximity to around eight million other people, Ms Mickenberg shuns many social connections and relationships. Instead, she enjoys time in her cave or experiencing the world outside alone.

And she’s not the only one living like this. Ms Mickenberg is the founder of “Hermettes”, a secret society of like-minded women who are reclaiming and celebrating female aloneness.

“Female aloneness is such a taboo … [But] I think this lifestyle needs to be idealised,” she tells ABC RN’s Sunday Extra.

‘Nothing more precious’

For much of her life, Ms Mickenberg was very sociable. She’s an accomplished writer and director, working in film, TV, theatre and advertising.

Also on her CV: Being the lead singer of an eight-piece power pop band called Jesus H Christ and the Four Hornsmen of the Apocalypse (with songs including ‘Connecticut’s For F**king’).

But Ms Mickenberg’s outlook about the world and her place in it changed as she got older.

“I was afraid of being alone. I wanted to be married and I wanted to have children,” she says.

“[Then] I had a few different experiences where I realised how much I loved to be alone … These experiences made me realise that there was nothing more precious than the time I spent with myself.”

So Ms Mickenberg decided she’d become a hermit.

The hermit lifestyle, or living in total seclusion, stretches back thousands of years. It’s played a role in different religions, seen as a road to spiritual betterment. In more modern times, it’s been a way to leave the social and economic structures of a community.

“Hermits have always had a place in society [but] it’s usually a male ideal … [So] the idea was to feminise the word,” she says.

Ms Mickenberg says she “summoned a bunch of people who I thought were fellow Hermettes” and launched the group — or what she proudly sums up as a secret society of antisocial, deep thinkers. With that, the group went their separate ways and the Hermettes were born.

“I’ve [since] seen, there are so many women who really love being alone,” Ms Mickenberg says.

“Instead of it being a shameful or embarrassing thing, or a secret, I think it should be something that we really want to do.”

The life of a Hermette

So what does the life of a Hermette involve?

The way Ms Mickenberg describes it, it’s not about entirely severing yourself from the rest of the world, but rather a choice to experience it alone, on your own terms.

Ms Mickenberg says the lifestyle can involve, “going into your shell and deciding how you really feel about things, what you really want, what you really want to say”.

When experiencing the outside world alone, “it actually makes you connect in a deeper way to other places … you find things, you run into things, when you’re not trying to continually connect to the same old four people [for example]”.

And Hermettes don’t have to be confined to one town or city.

“I think part of the Hermette lifestyle is travelling all over the world, and being alone in new places, because you connect with people and places differently when you travel alone.”

But it’s not all serious: Hermettes also get creative, even subversive, in their aloneness.

Wooden phones and an (occasional) magazine

Some Hermettes choose to be less reliant on certain technologies than the rest of the population.

In this vein, Ms Mickenberg developed special Hermette mobile phones, which are described as “phone-shaped hunks of wood that get zero reception no matter where you are”.

According to material from (not-an-actual-telco) “Hermette Wireless”: “Your phone does not get Twitter, Facebook, Instagram or Parler. You won’t get texts, calls or emails. No meditation apps. No productivity apps. No apps at all. No podcasts. No maps. No games. No camera. Nothing.”

What, at first glance, seems totally useless, these wooden faux-phones are a symbol of the movement — a proud disconnection from the social networks many of us rely on.

And although it may sound like a contradiction, there’s a thriving Hermette network, connected through Ms Mickenberg’s Hermette Magazine.

It’s described as “a publication that only comes out when it feels like it”.

“I think magazines come out much too often. I don’t know what this [every] month thing is, or this weekly thing, or the daily thing … So why not publish a magazine

when you really feel like you have something to say?” Ms Mickenberg says.

Only a handful of issues have come out, with articles including “News for the modern recluse” and “Why the post office Is even more awesome than you think it is”.

Not just women

Since launching, the Hermettes have expanded beyond New York City and now have dozens of members all around the world.

While much of the group’s philosophy is centred around women’s experiences, Ms Mickenberg insists anyone can be a Hermette.

“People of all genders can be Hermettes,” she says, adding that even a family can adopt a Hermette lifestyle.

“It’s aloneness for people who may have felt a bigger obligation to connect with other people … [And] people who give their lives over to other people too easily — it’s even more important for them to treasure their aloneness.”

Ms Mickenberg hopes one day societies can become more accommodating of aloneness, for example, “having restaurants where everybody sits individually, even if you go there as a group”.

“You might meet other people,” she says.

“There are a lot of successful things that could happen in the world if we treat everybody as an individual,” she says.

And whether the Hermette lifestyle is for you or not, Ms Mickenberg says we could all benefit from rethinking aloneness.

“I think that [we can all] connect to our aloneness in a good way and know that people don’t need to be with each other all the time,” she says.

Cindy Lou breakfasts at Kopiku in O’connor

Kopiku is an interesting venue as the new owners began trading during the pandemic and eventual lockdown. They are still there , and thriving. Kopiku was the first successful iteration of this formerly very popular cafe, 39 Steps. As 39 Steps it had quite a bohemian atmosphere, dog drinking dishes, and the staff were unfailingly friendly. The food was excellent. Alas, with a couple of changes of ownership, the tables became emptier and emptier. Dislike of dogs and unfriendliness were the keys to these owners’ lack of success. And then, Kopiku arrived – and the tables were filled again, with people sighing with relief that a friendly atmosphere had returned (and the dog bowl). A welcome addition to the usual breakfast fare of eggs with extras, toast, cereal and pastries, has been the Indonesian food. Indonesian dishes are served at breakfast and lunch, and there are some dinner sessions (Thursday and Friday) as well. They are an excellent addition to the pizzas as a lunch or dinner meal, as well as breakfast.

8 Women Directors from Around the World You Should Be Watching

David Jenkins on Ava DuVernay, Isabel Sandoval, and More July, 21 2022.

If you type the words “Great Film Directors” into Google, you have to scroll past 45 portraits of male filmmakers before you read the first woman: Kathryn Bigelow. Many of the great books which survey the important film directors of our time are tethered to an old guard canon where it pays to be a man.

With Filmmakers on Film, we set out to disrupt the conventional thinking about who gets to make films and who should be celebrated for that fact—and the aim of this was not just in the name of enforced diversity, but to actually acknowledge the expanded richness of a film culture where work is being made by a mix of genders, and not just by people with white skin.

*

Vera Chytilová

Born: 1929 / Nationality: Czech

The brilliant Czech filmmaker Věra Chytilová wore the description “abrasiveness” as a stylistic badge of honor, and she addressed her audience in a thrillingly confrontational manner.

Take, for example, her 1979 film Panelstory, which seeks to recreate the experience of life in a hideous Soviet housing conurbation, with camerawork that teeters just on the right side of the queasily voyeuristic, and shrill sound design that makes you want to bury your head in a pillow. And yet she taps into essential truths about the dynamics of community and the irritating aspect of close quarters living.The brilliant Czech filmmaker Věra Chytilová wore the description “abrasiveness” as a stylistic badge of honor, and she addressed her audience in a thrillingly confrontational manner.

The film she is best known for, however, is 1966’s Daisies, a non-narrative exploration into rebellion and political anarchism in which two young women casually reject the timeworn precepts of feminine politesse and proceed blithely to destroy everything and everyone around them.

Even though Chytilová worked with symbolism and allegory to articulate her strident political convictions, she was blackballed from making films in communist Czechoslovakia for perceived seditious activity, and she often found it hard to keep working. Yet this seam of abrasiveness is cut through with sincere passion and a tremendous eye for striking juxtapositions—both visual and thematic. Her outrageous revenge film Traps (1998) sets its male-genital-slashing agenda with scenes of piglets being neutered, while her more wistful and reflective debut feature, Something Different (1963), sets dueling tales of a modern ballet dancer and a harried housewife side by side to present the crushing toils of womanhood.

Joanna Hogg

Born: 1960 / Nationality: British

Since its earliest days, the movie star has been a valuable marketing asset for those in the business of selling dreams. Yet seeing these faces over and over, being made aware of a person’s celebrity status, makes it more difficult for an audience member to fully suspend disbelief. British director Joanna Hogg has, across a small but impressive body of work, prized the thrill of the new and has cast her films against the grain of name recognition. What she omits when acknowledging the pleasure she gleans from bringing new souls to the screen is that her films are all deeply personal and self-reflective—filmmaking as a concave mirror that offers a lightly warped but always discernible impression of messy reality.British director Joanna Hogg has, across a small but impressive body of work, prized the thrill of the new and has cast her films against the grain of name recognition.

Her feature debut, 2007’s Unrelated, presents itself as a satire on the elegant slumming of upper-middle-class English dandies, but is slowly revealed to be a painful rumination on the psychological effects of the menopause, seen largely in the awkwardly flirtatious relationship between timorous 40-something Anna (Kathryn Worth) and braying posh boy Oakley (Tom Hiddleston, in his feature debut). It appears to be cinematic biography, though one fashioned from private impulses and interior reflection. The Souvenir (2019) is Hogg’s most openly autobiographical film, and in this instance she counteracts the rawness of the memories as they come to her by casting her first major movie star, Tilda Swinton—though it’s Swinton’s real-life daughter who is the film’s focal point and a proxy for the director herself.

Cheryl Dunye

Born: 1966 / Nationality: Liberian–American

Justine is the name of the 1990 debut short feature by filmmaker Cheryl Dunye, and it contains the thematic DNA for all of her work up to and including her feature breakout—1996’s The Watermelon Woman. Dunye’s radical film work explores Black sexuality, interracial relationships, depictions of sex and the insidious racism and class bias within lesbian social cliques. The director herself often appears on screen, usually addressing the camera and spinning a yarn that come across as an erotically inclined diary entry. Her tone oscillates between the casually flip and the perpetually irritated, and we often see comic recreations of her words. A little like Spike Lee, Dunye articulates weighty ideas but both leavens and empowers them with humor and an intuitive feel for Black subcultures.Dunye’s radical film work explores Black sexuality, interracial relationships, depictions of sex and the insidious racism and class bias within lesbian social cliques.

While 1993’s The Potluck and the Passion and 1995’s Greetings from Africa are both dating comedies that pack a considerable political punch, The Watermelon Woman is revelatory in how it places all of Dunye’s prior concerns in a historical context—in this case, the presence of a mysterious silent film actress who is credited as “Watermelon Woman” and with whom the director, played by Dunye, becomes fixated. Her search for this enigmatic screen presence runs parallel to her romance with a white woman, and the film concludes that Black people—in art and life—exist only to appease the fragile, do-gooding egos of their white counterparts.

Lucrecia Martel

Born: 1966 / Nationality: Argentinian

María Onetto, star of Lucrecia Martel’s 2008 film The Headless Woman, plays Vero, a bourgeois housewife who, while driving along a country road, glances down at her mobile phone momentarily and feels something roll underneath her tires. Convincing herself it’s a dog, she carries on with the trivialities of family life. Yet the uncertainty of this moment—of why she rejected the impulse to find out exactly what happened, an impulse perhaps born of societal duty—weighs heavily on her. Aspects of her life unravel. The incident is illustrative of a moment of realization and possible regret. The film offers a moral quandary, but also places us there on the path of warped perception. Could this all just be a nightmare? Martel’s four feature films all zero in on protagonists who are largely blind to the world in which they are cocooned—suffering, exploitation, political corruption, religious zealotry, you name it.Martel’s four feature films all zero in on protagonists who are largely blind to the world in which they are cocooned.

From the elegantly slumming middle-class wastrels in 2001’s The Swamp, to a preening 18th-century government administrator desperate to save his own hide in 2018’s Zama, Martel’s films are woozy, quixotic, and disorientating. She lures us into a sensibility of experimentation but ends up articulating her thesis of innate human selfishness with daunting clarity.

Ava DuVernay

Born: 1972 / Nationality: American

It’s hard to consider Ava DuVernay’s 2014 film Selma without thinking about the relentless thud of marching boots. It is the sound of an inexorable march towards progress, an unbreakable rhythm that cannot and will not be interrupted. Her film tells of a peaceful protest staged by Martin Luther King Jr. (David Oyelowo) in response to racially motivated violence and discrimination in the state of Alabama. A symbolic journey must be made between Selma and Montgomery, the sites of twin atrocities, and DuVernay stages this historical happening with a surface-level cool that barely masks the strident urgency of her all-too-prescient story.

As a filmmaker, DuVernay displays a selflessness that is fitting of Dr, King himself, in that, since the success of Selma, she has parlayed her considerable industry clout into amplifying an ethnically diverse range of voices through her ARRAY production and distribution outfit. Her abiding interest in America’s dismal history of institutionalized Black oppression surfaced again in the 2016 documentary 13th, which convincingly demonstrated how the prison industrial complex is an example of modern slavery, a practice supposedly outlawed by the 13th Amendment of the US Constitution.DuVernay is emblematic of the idea that every choice you make as a director is loaded with social relevance, even if you don’t mean it to be.

Even her intriguing 2018 children’s fantasy film, A Wrinkle in Time, challenged tired Hollywood notions of screen representation by being centered on a Black teenage girl traveling through a fluorescent fantasia in search of her lost father. DuVernay is emblematic of the idea that every choice you make as a director is loaded with social relevance, even if you don’t mean it to be.

Mia Hansen-Løve

Born: 1981 / Nationality: French

Autobiography tends to fillet the most dramatically pertinent events from any given timeline and place them at the forefront of a narrative. French director Mia Hansen-Løve does things a little differently. She somehow manages to see through the episodic minutiae of life and visualize grand emotional arcs that pivot around a single transformative moment. The way in which she unselfconsciously presents and frames the notable incidents of her own life with such candor and peculiar detail is moving in and of itself. And she does so in a way that recognizes the malformed and often ill-timed nature of life’s high dramas, that personal histories can encompass the timespan of an existential awakening rather than just a bunch of interesting events.She somehow manages to see through the episodic minutiae of life and visualize grand emotional arcs that pivot around a single transformative moment.

Two of her greatest works concern characters jack-knifed out of a state of idle comfort. Goodbye First Love (2011) appears initially to be a star-crossed teenage romance, until it’s eventually revealed to be a film concerning the death of love and the slow grieving process that comes in the wake of that death.

Then there’s Eden (2014), which furtively charts the evolution of Euro house music in the 1990s as filtered through the life of the director’s own brother. He spent his early years as an aspiring DJ until he reached a point where continuing in the profession he loved became impossible. An epiphany ensues. On that note, all of Hansen-Løve’s philosophically rich films reflect on the affirmative or educational aspects of tragedy.

Isabel Sandoval

Born: 1982 / Nationality: Philippines

The cinema of Isabel Sandoval presents life as a compound of sensuality and crippling unease. She sculpts characters whose lives are dictated by the inexorable ebb and flow of political power structures. In 2019’s Lingua Franca, Sandoval plays Olivia, an undocumented trans immigrant living in Brooklyn who works as a caregiver. She enters into a sexual relationship with her client’s foolhardy son while doing her best to evade the authorities who seem, from every angle, to be closing in on her.

Sandoval’s cinema is pathfinding in its progressive depiction of trans characters, as they are more than the sum total of their sexual hang-ups and gender dysmorphia. Her films ask, how can we amply explore the sensuality of our souls and the nature of our identity when the walls are constantly closing in on us?

In her remarkable debut feature, Señorita (2011) which was made in the Philippines, she plays a trans escort who, by a twist of fate, suddenly finds herself in the parochial world of local politics. Again, her character passes back and forth between two bisecting worlds: one of sexual danger; another of paranoia and small-town government conspiracies.Sandoval’s cinema is pathfinding in its progressive depiction of trans characters, as they are more than the sum total of their sexual hang-ups and gender dysmorphia.

Perhaps her pièce de résistance as a filmmaker, however, is an audacious sex scene in Lingua Franca which holds the camera firmly on Olivia’s face as she experiences pleasure—according to Sandoval, an example of something elusive so far in the annals of cinema: the “trans female gaze.” The sequence also suggests something utopian about sexual desire—the communion of bodies as the only respite we have from the dismal world outside.

Jane Campion

Born: 1954 / Nationality: New Zealander

In Jane Campion’s multi-award-winning 1993 feature The Piano, Holly Hunter’s mute waif conducts a series of erotic relationships with her husband, another man, her daughter, and the instrument referenced in the film’s title. The power of The Piano derives from the way the writer–director minutely calibrates (and differentiates) the emotional tenor of each relationship: through framing and performance, and also by ushering the dramatic contours of the landscape—a sodden beachside settlement in 19th-century New Zealand—into the heart of her tragic heroine. Indeed, bodies and landscapes are one and the same in this film: both are to be explored, sometimes with tenderness, sometimes with brutality.Campion’s films are notable for their rhapsodic artistry, as well as for the centering of female desire that, in its intensity, traverses the full spectrum of emotions.

Campion has long been interested in cautious, reticent women and how they navigate a terrain of suppressed sexual longing, interpersonal dysfunction, artistic fulfillment and professional fortitude. Her 1990 masterpiece An Angel at My Table chronicles the formative years of poet and author Janet Frame, rejecting a conventional narrative arc in favor of presenting life as a meandering stream of confusion and indignity. Meanwhile, 2009’s Bright Star details an intense love affair between the Romantic poet John Keats and his neighbor Fanny Brawne that withers before it has a chance to fully blossom. The relationship is scuppered—as it so often is—by the fragility of the human body. Campion’s films are notable for their rhapsodic artistry, as well as for the centering of female desire that, in its intensity, traverses the full spectrum of emotions.

________________________________