This week I review Paul Kendall’s Queen Elizabeth I Life and Legacy of the Virgin Queen which fits nicely into thinking about the article by Jenny Hyde on the way in which news about the death of Queen Elizabeth 1 compares with news coverage of the death of Queen Elizabeth 11.

Paul Kendall Queen Elizabeth I Life and Legacy of the Virgin Queen Pen & Sword Frontline Books, 2022.

Thank you NetGalley, for providing me with this uncorrected proof for review.

Paul Kendall’s prose misses the vivacity to which I have become accustomed in publications by Pen & Sword. Rather, he has written a book that outlines methodically the material he is investigating, while bringing it to the wider audience to whom the accessibility offered by these publications is important. Where Kendall has excelled is in the approach that he has taken to the material. Where other writers use photographs, artifacts documents and illustrations to enhance the text, Kendall has used them as the focus of the text – they are the ‘jumping off ‘ point for the information he has garnered about this fascinating period and figure. Books: Reviews

Covid Canberra

The new cases recorded on 23 September, for the period Thursday 15 September to 4pm Thursday 22 September, were 730. There are 69 people in hospital suffering from Covid, and none in ICU or ventilated. No lives were lost this week.

Jenny Hyde

Lecturer in Early Modern History, Lancaster University

The Conversation

In 2022 TV news rather than ballads communicate the details of a monarch’s death, but the challenge of communicating the royal succession draws on lessons from 400 years ago

How news of the death of Elizabeth I in the 17th century was communicated in ballads and proclamations

Published: September 17, 2022 1.17am AEST

When Queen Elizabeth II passed away on September 8, 2022, there can’t have been many people in the UK who hadn’t heard about it within hours of her death. The media was on high alert from around midday, when an announcement from Buckingham Palace made clear that the monarch’s health was under threat.

The BBC replaced normal programming with rolling news coverage. And as soon as the announcement of the Queen’s death was posted on the gates of Buckingham Palace, just before 6.30pm, news presenters interrupted programmes across the board to inform the public. The news, after all, is at our fingertips 24/7.

By contrast, when Queen Elizabeth I died in Richmond Palace, near London, on March 24, 1603, the news didn’t arrive in Berwick-upon-Tweed in Northumberland, around 550km away, until two days later. The proclamation that brought news of her death and of James I’s accession took almost two weeks to reach Ireland.

In the days before mass media and high levels of literacy, news travelled slowly. Like our current press, however, early tools for communicating this kind of momentous event trod the same tricky path of celebrating the late queen’s reign, mourning her passing and heralding the new king’s arrival. Striking the right tone to reflect the nation’s grief and commemorate a distinguished life has always been crucial.

How news spread in the 17th century

When Elizabeth I died in 1603, James VI of Scotland became James I King of England and Ireland as well. We know that many people across England, Wales and Ireland found out about this through proclamations, songs and other forms of oral communication.

Research shows how even pamphlets were often designed to be read aloud, for example, by using punctuation to instruct readers when to pause or breathe. They recognised that printed texts were shared socially among groups of family and friends.

These items could be described as the social media of their day. The simple, popular songs known as ballads could be composed and printed within a matter of days. They were easy to distribute and cheap to buy. Above all, they were based on face-to-face communication and public performance.

Fanfares of drums and trumpets of the kind that preceded the principal proclamation of King Charles III at St James Court on September 10, 2022 were also often used to grab people’s attention for the proclamations which were heard in Tudor and Stuart marketplaces.

Ballads were ideal for disseminating this sort of news and information too. Like proclamations, they were performed in marketplaces, but they could also be heard at fairs and in taverns – anywhere where an audience could gather. Though the lyrics were often printed, they mostly spread by word of mouth. And they deliberately used techniques that made them easy to remember, including rhyme, rhythm and repetition.

The chorus of one ballad about Elizabeth I’s death, called A Mournful Ditty, combined repetition, alliteration and rhyme with a melody. It was perfectly crafted for singers to join in:

Lament, lament, lament you English peers, Lament your loss possessed so many years.

A dual focus

These days, of course, it would be rare to learn about a major news event from a song. But the lyrics of that ballad show how the fundamental problems facing the media today on the death of a sovereign were the same 400 years ago.

The immediate focus is on grief. For there to be mourning, there also needs to be a sense that something cherished has been lost. So even while celebrating the peace and stability of her impressive 44-year reign, the ditty praised Elizabeth I as “the paragon of time” and urged its listeners to:

Weep, wring your hands, all clad in mourning

But the death of one monarch marks the accession of another. And the focus of the cheapest print – ballads – quickly shifted to the new monarch. This is probably because James I faced one issue that Charles III does not.

In contrast to Charles III – who is a familiar figure from his many years as the heir apparent – James was, to the English, Welsh and Irish, king of a foreign state. What is more, Elizabeth I had refused to name him as her successor. There were any number of rival claims to her throne.

Several ballads combined mourning the Queen’s passing with introducing the Scottish king to his new subjects. They highlighted continuities, including James’s English ancestry as great-great-grandson of Henry VII.

Pamphlets described his journey from Edinburgh and ceremonial entry into London in detail. One song even went so far as to falsely claim that Elizabeth I had “assigned all her state to our Noble King James”. Presumably this was part of a narrative that smoothed his accession by setting him up as the rightful heir to the throne.

One printed sheet, Weep with Joy, described Elizabeth as an example of piety, humility and mercy whose loss should be lamented. It also noted that James’s accession was a cause for celebration. His proclamation, the pamphlet states, was “read and received with great applause of the people”.

How true this was is debatable. One diarist noted that the proclamation was heard with “silent joy”, though this was in part down to relief that James had succeeded peacefully.

This narrative of continuity can now be seen in the way Charles III’s speeches and statements draw on his mother’s reputation. Although a succession crisis was never on the cards, his accession has been greeted with misgivings by some. Maybe even in the 21st century, the dual focus of news helps to strengthen the bond between the new monarch and the old, smoothing the transition of power even as it creates tensions for the media.

Republished from The Conversation under Creative Commons licence.

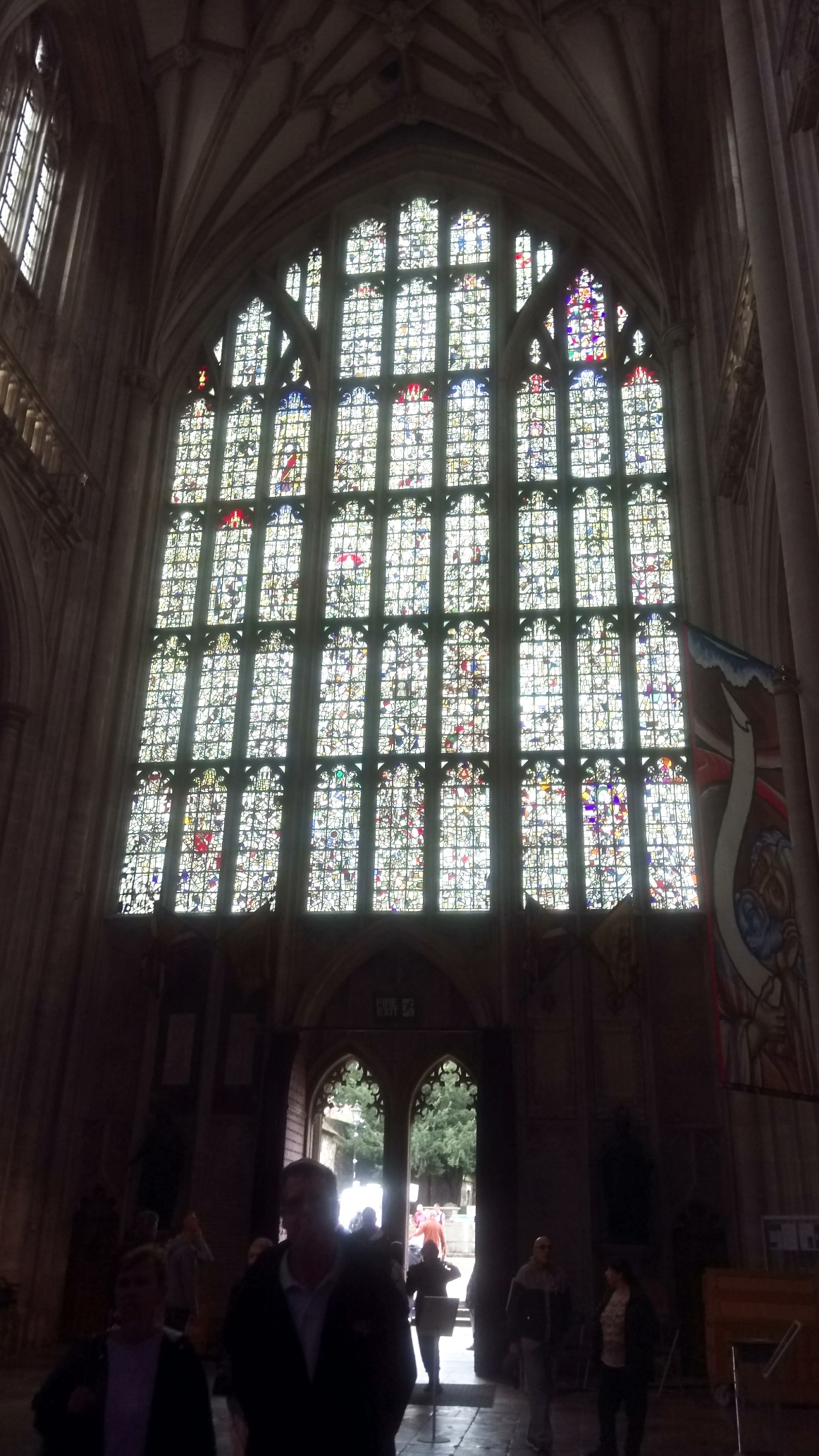

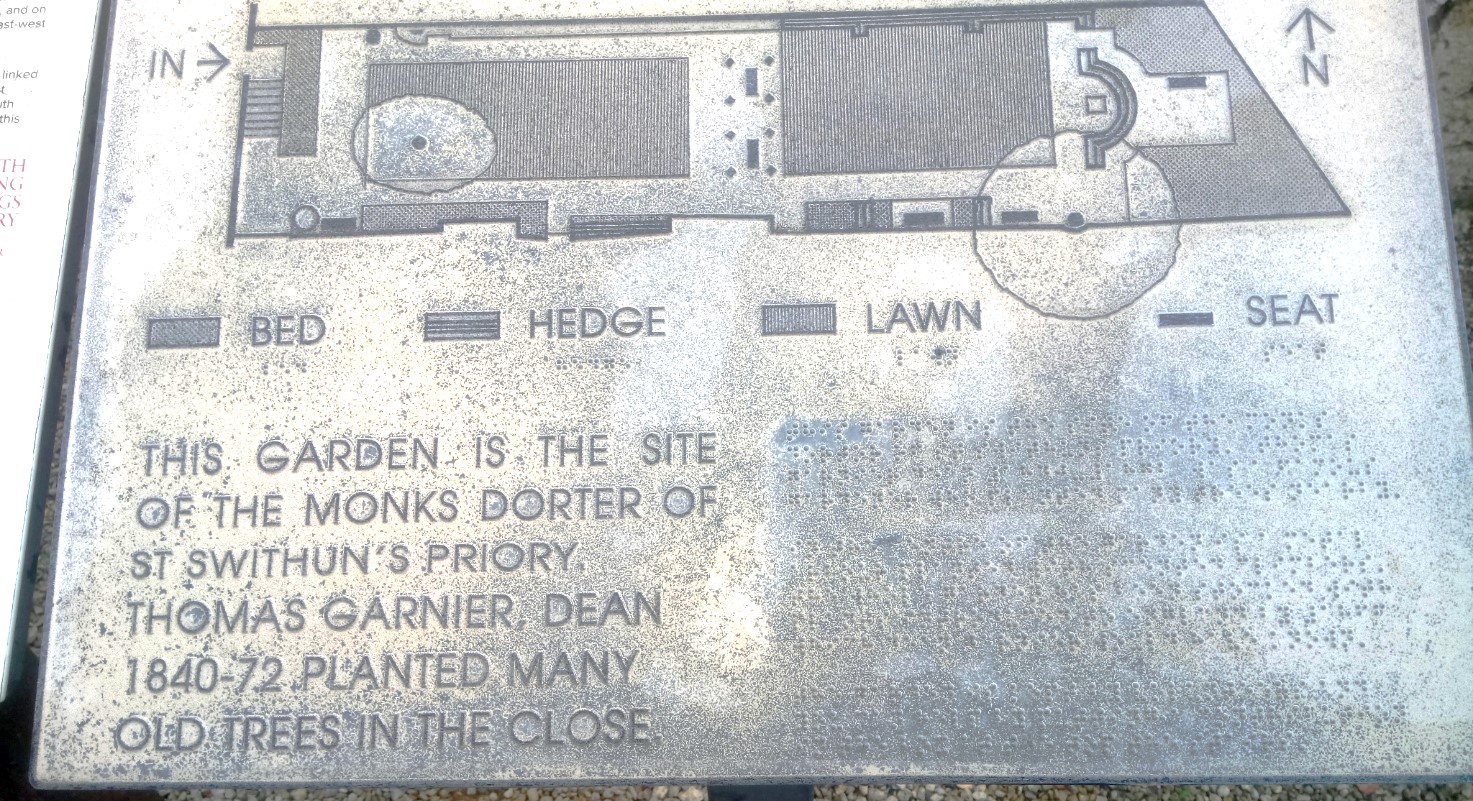

Visit to Winchester Cathedral

I did not know about the wedding chair used by Queen Mary 1 in her marriage to Philip of Spain (mentioned in the review of Queen Elizabeth I Life and Legacy of the Virgin Queen) so did not look for it on my visit to Winchester Cathedral. My focus was on Jane Austen and her burial there, and the memorials were worth the visit. They will feature next week , together with the review of a book about her.

Winchester is about an hour’s train trip from London, and again I wish I had read Kendall’s book before my visit. On the way back I could have imagined the arduous trip made by Mary and Philip, in comparison with mine on a smoothly running train, comfortable seating, a coffee bought on the platform in my hand, and upon arrival at Paddington, a short walk to my hotel. Best of all, no crowds of mixed intent along the wayside.

Hilary Mantel, Prize-Winning Author of Historical Fiction, Dies at 70

The two-time Booker Prize-winning author was known for “Wolf Hall” and two other novels based on the life of Thomas Cromwell.

Sept. 23, 2022, 6:51 a.m. ET

Hilary Mantel, the British author of “Wolf Hall,” “Bring Up the Bodies” and “The Mirror and the Light,” her trilogy based on the life of Thomas Cromwell, died on Thursday at a hospital in Exeter, England. She was 70.

Her death, from a stroke, was confirmed by Bill Hamilton, her longtime literary agent. “She had so many great novels ahead of her,” Mr. Hamilton said, adding that Ms. Mantel had been working on one at the time of her death. “It’s just an enormous loss to literature,” he added.

Ms. Mantel was one of Britain’s most decorated novelists. She twice won the Booker Prize, the country’s prestigious literary award, for “Wolf Hall” and “Bring Up the Bodies,” both of which went on to sell millions of copies. In 2020, she was also longlisted for the same prize for “The Mirror and the Light.”

American support for unions

| Union approval highest in 57 years |

Data: Gallup. Chart: Madison Dong/Axios Visuals71% of Americans approve of labor unions — the highest reading since 1965, according to Gallup.Approval is 89% for Ds … 56% for Rs.Why it matters: Retail, warehouse and fast-food workers — empowered by the tight labor market — have made union inroads at Starbucks, Amazon and Chipotle. Data: Gallup. Chart: Madison Dong/Axios Visuals71% of Americans approve of labor unions — the highest reading since 1965, according to Gallup.Approval is 89% for Ds … 56% for Rs.Why it matters: Retail, warehouse and fast-food workers — empowered by the tight labor market — have made union inroads at Starbucks, Amazon and Chipotle. |

Cressida Campbell exhibition at National Gallery of Australia cements underrated Australian artist’s place in the canon

A mural-like painting of an intricately adorned kitchen shelf wraps the entrance to the National Gallery of Australia’s newest exhibition.

In it, an array of household objects are celebrated with exceptional precision: a leek is propped against a blue and white ceramic vessel, black kitchen scissors protrude from a white milk jug, a sprig of lavender rests idly.

The more you look, the more you see.

The mural is an enlarged version of Australian contemporary artist Cressida Campbell’s 2009 woodblock painting The Kitchen Shelf — here, lovingly recreated by her husband Warren Macris, who is a fine art and photographic printer and took more than 100 photographs of the original to make the mural.

Opening Saturday, the exhibition is a major retrospective of Campbell’s work, featuring more than 140 of her woodblock paintings and woodcut prints.

At 62, Campbell has been making art for more than 40 years, and in sales alone, she’s one of Australia’s most successful and sought-after artists (her commercial shows typically sell out, often before opening) — but this is the first time a retrospective of this scale has been mounted by a major Australian gallery.

It’s also the first time the National Gallery of Australia (NGA) has programmed a living Australian artist for their summer ‘blockbuster’ exhibition — a spot usually reserved for broadly recognisable international artists (think: Picasso).

“[Campbell] is a very well-established artist and we believe that she’s contributed something very unique to the cultural tapestry of Australian art,” NGA director Nick Mitzevich tells ABC Arts.

“She’s at the peak of her powers and we want to celebrate that.”

Curated thematically across six rooms, the exhibition is autobiographical, featuring intimate domestic scenes, city- and landscapes from the places Campbell has lived, and even childhood drawings.

“It’s a bit like a documentary, but in paint,” the artist told ABC News.

Mitzevich says: “The exhibition reveals itself slowly to you and seduces you in because of the build-up of colour, the nuance of the way she models a form, or a shape, or a shadow, and how she captures beauty.

“For me, this exhibition is a journey of beauty.”

Working from her backyard studio in Sydney (Warrang), Campbell draws inspiration from her surroundings, including her garden and household objects.

There is an unexpected beauty in the mundanity of the scenes and objects she depicts: kitchen scraps in a plastic ice cream container; nasturtium cuttings cascading from a wine glass; a shock of grey fur (Campbell’s previous cat Otto) tucked behind a staircase railing.

The domesticity of her subjects is deeply intimate.

“[They’re things] people wouldn’t normally relate to as interesting subjects, but they actually look interesting to me,” Campbell says.

“So it’s a way of encouraging people to re-see things.”

Making the everyday extraordinary

Campbell’s creative process is highly unusual for a contemporary painter.

She first draws then etches scenes onto a block of plywood, before applying multiple layers of watercolour paint using fine sable brushes. She then mists the block with water and lays paper over the top, pressing and rolling the block by hand to create a mirror print.

There is a reverence in this approach, which draws on Ukiyo-e — a Japanese woodblock printing style that Campbell studied while living in Tokyo in the 80s.

She also cites Australian painter and printmaker Margaret Preston as a key stylistic influence. Campbell was particularly taken with Preston’s woodcuts after discovering them at an Art Gallery of NSW (AGNSW) exhibition in the late 70s, while studying art at East Sydney Technical College (now the National Art School).

Campbell takes several months to make each woodblock and single-edition print, producing roughly five to six works per year.

“I actually spend a lot of time retouching and hand-painting the print because there’s often quite a lot of it that needs work,” she told her sister, the actor Nell Campbell, earlier this year.

It’s a painstaking process to capture what are, for the most part, everyday objects and scenes. (Piles of used paint tubes and brushes on display as part of the exhibition attest to the labour.)

But Campbell’s deliberateness and astonishing attention to detail render the everyday extraordinary.

Dr Sarina Noordhuis-Fairfax, the NGA’s curator of Australian prints and drawings, says Campbell, who is not particularly comfortable in the limelight, lets her work speak for itself.

“Her work finds its way out into the world without having to do any sort of banging of the drums about it.

“I think lots of people will recognise her work, but not realise who made it. And I think that’s the beauty of doing a show like this: people will begin to know the name Cressida Campbell.”

Noordhuis-Fairfax collaborated with Campbell on the retrospective, which includes several of the artist’s childhood artworks. (Campbell has been drawing since she was six years old.)

“She’s an artist that just never stopped drawing,” Noordhuis-Fairfax says.

“They’re quite exceptional drawings, and you can see that real interest in the natural world and that [her] attention to detail started really young.”

Course correction

While Campbell may not be a household name, Mitzevich says he hopes the exhibition will help to change that.

“What I’m really heartened about is that the work and her practice will certainly take a big step in recognition through this major exhibition,” he says.

“We hope that hundreds of thousands of Australians will have the opportunity to see [Campbell’s] work and appreciate how unique her practice is.”

The NGA has acquired a new work, Bedroom Nocturne (2022), from the exhibition, bringing the total number of Campbell’s works held by the gallery to five.

Of the major Australian galleries, the Art Gallery of NSW (AGNSW) has collected nine of Campbell’s works (including four donated by Olley, an early champion of the artist), while Queensland Art Gallery and Gallery of Modern Art (QAGOMA) holds one.

Major Australian galleries such as the National Gallery of Victoria, Museum of Contemporary Art and the state galleries of Western Australia and South Australia do not currently hold any of Campbell’s work in their permanent collections.

Meanwhile, Mitzevich says, she is one of the most privately collected Australian artists.

The exhibition features the highest number of private loans the NGA has included in a single exhibition — 111 in total, representing 80 per cent of the works exhibited.

Having worked consistently over the past four decades, it’s fitting that Campbell’s retrospective has been programmed in the NGA’s 40th year. (Serendipitously, she attended the NGA’s opening in October 1982 as the plus-one of artist Martin Sharp.)

Her exhibition is one of 18 projects announced to date that have been commissioned as part of the NGA’s Know My Name gender equity initiative, which was established in response to findings that only one-quarter of the gallery’s Australian collection and one-third of its Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander collection is by women artists.

Mitzevich says of Know My Name: “It’s not about being ‘woke’ or politically correct. It’s about acknowledging that, in our culture, the playing fields for various things are uneven … and it’s important to elevate the parts that haven’t been given a fair go.

“And we are unapologetic about that,” Mitzevich adds.

The exhibition is not just a significant professional milestone for Campbell but a personal one too. In August 2020, she developed a life-threatening brain abscess that paralysed one side of her body and required multiple operations.

She has spoken previously about the horrible moment, in the aftermath, when she realised she might never be able to paint again.

Those operations restored Campbell’s use of her right arm and leg, which in turn allowed her to complete the new work that features in the NGA exhibition.

Campbell told ABC News that being able to have a survey exhibition at NGA was an “amazing compliment”.

“I couldn’t feel more honoured. It’s incredible.”

Cressida Campbell runs until February 19, 2023 at the National Gallery of Australia.