The book I review this week is, in my opinion, somewhat of a throwback to a different age. Of course, the attitudes of the time were of a different age, but their perpetuation in the 2020s is an interesting phenomenon. To be fair, the title is modern – no ‘air hostesses’ here! Despite this proviso, comparing this book with one I reviewed last year, which I refer to briefly below, demonstrates the way in which reflection on the past does not need to perpetuate the sexism of an earlier era.

The covers are a bit of a giveaway!

Another connection with a previous book I reviewed is in a letter by Heather Cox Richardson, see below. I reviewed Fearless Women by Elizabeth Cobbs in the 17th January blog. I questioned the inclusion of Phyllis Schlafly. Now my queries have been justified by a reference to in a story about the US Supreme Court’s overturn of Roe vs Wade. See below, Letters from an American, Heather Cox Richardson.

NetGalley provided me the following uncorrected proof for review.

True Tales of TWA Flight Attendants Telemarchus Press, 2022.

Kathy Kompare and Stephanie Johnson have assembled a variety of short stories about the early years of TWA, concentrating on their impact on the flight attendants. Reading these stories is like having a conversation with a bubbly flight attendant, with a dash of seriousness thrown in to keep the central the light-hearted approach realistic. Although the stories concentrate on the pleasure of being a TWA flight attendant, there are serious moments as well, adding to the value of the record. That being said, this book was not for me. Books: Reviews

After the Covid Report: Elizabeth Cobbs and reference to Phyllis Schlafly; Come Fly the World in reference to True Tales of TWA Flight Attendants; Heather Cox Richardson – childcare (Congressional Dad’s Caucus) and National Database of Childcare Prices – childcare costs in America; Cressida Campbell exhibition at the NGA; and Letters from an American – Roe vs Wade.

Covid Report Canberra since lockdown ended

New cases this week number 528, with 22 in hospital, 1 in ICU and 1 ventilated. Four lives were lost this week.

Elizabeth Cobbs, Fearless Women Feminist Patriots from Abigail Adams to Beyoncé Harvard University Press, Belknap Press, March 2023.

Elizabeth Cobbs expands the way in which feminism is used to investigate women who call themselves feminists, and some who do not, worked to improve ‘their country’… However, rather than let the broadness of Cobb’s view limit the way in which this book is read, I found it an energising read, with a lot with which I could identify, some that left me questioning (Phyllis Schlafly a feminist?), engrossing stories of marvellous women, horrendous stories of the treatment of women and the beliefs that underlie such treatment, and a veritable wellspring of information. Books: Reviews for 17th January and see Letters from an American below.

Julia Cooke Come Fly The World The Jet-Age Story of the Women of Pan Am was given to me by NetGalley as an uncorrected copy for review. I thought that True Tales of TWA Flight Attendants might be similar, although related to a different airline. I was wrong, as can be seen from my review.

Selections from the review for Come Fly the World provide examples of how stories from a past gendered era and profession can be brought into the 2020s.

The journey Julia Cooke describes through the stewardesses (as they were during most of the period Cooke covers, the gender-neutral title ‘flight attendant’ being adopted only at the end of this era) recognises the value of reflecting upon the past from a 2020s perspective.

There are three sections: THE WRONG KIND OF GIRL; YOU CAN’T FLY WITH ME; and WOMEN’S WORK. WOMEN’S WORK identifies the range of events for which the flight attendants had trained: Everything flyable, War Comes Aboard, The Most Incredible Scene and The Only Lonely Place Was on the Moon…Cooke combines personal stories with events such as the Vietnam War and its impact on American politics, soldiers, stewardesses and Vietnamese.

The complete review is at Books: Reviews, to be found on the pages relating to the post of 17 March, 2022.

Heather Cox Richardson

January 28, 2023 (Saturday)

Two relatively small things happened this week that strike me as being important, and I am worried that they, and the larger story they tell, might get lost in the midst of this week’s terrible news. So ignore this at will, and I will put down a marker.

At a press conference on Thursday, Representatives Jimmy Gomez (D-CA), Rashida Tlaib (D-MI), Daniel Goldman (D-NY), Andy Kim (D-NJ), Joaquin Castro (D-TX), Jamaal Bowman (D-NY), Joe Neguse (D-CO), Eric Swalwell (D-CA), Ruben Gallego (D-AZ), Colin Allred (D-TX), Mike Levin (D-CA), Josh Harder (D-CA), and Raul Ruiz (D-CA), and Senator Rob Menendez (D-NJ), announced they have formed the Congressional Dads Caucus.

Ironically, the push to create the caucus came from the Republicans’ long fight over electing a House speaker, as Gomez and Castro, for example, were photographed taking care of their small children for days as they waited to vote. That illustration of men having to adjust to a rapidly changing work environment while caring for their kids “brought visibility to the role of working dads across the country, but it also shined a light on the double standard that exists,” Gomez said. “Why am I, a father, getting praised for doing what mothers do every single day, which is care for their children?”

He explained that caucus “is rooted in a simple idea: Dads need to do our part advancing policies that will make a difference in the lives of so many parents across the country. We’re fighting for a national paid family and medical leave program, affordable and high-quality childcare, and the expanded Child Tax Credit that cut child poverty by nearly half. This is how we set an equitable path forward for the next generation and build a brighter future for our children.”

The new Dads Caucus will work with an already existing caucus of mothers, represented on Thursday by Tlaib.

Two days before, on Tuesday, January 24, the Women’s Bureau of the U.S. Department of Labor released its initial findings from the new National Database of Childcare Prices. The brief “shows that childcare expenses are untenable for families throughout the country and highlights the urgent need for greater federal investments.”

The findings note that higher childcare costs have a direct impact on maternal employment that continues even after children leave home, and that the U.S. spends significantly less than other high-wage countries on early childcare and education. We rank 35th out of 37 countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) made up of high-wage democracies, with the government spending only about 0.3% of gross domestic product (GDP) compared to the OECD average of 0.7%.

These two stories coming at almost the same time struck me as perhaps an important signal. The “Moms in the House” caucus formed in 2019 after a record number of women were elected to Congress, but in the midst of the Trump years they had little opportunity to shift public discussion. This moment, though, feels like a marker in a much larger pattern in the expansion of the role of the government in protecting individuals.

When the Framers wrote the U.S. Constitution, they had come around to the idea of a centralized government after the weak Articles of Confederation had almost caused the country to crash and burn, but many of them were still concerned that a strong state would crush individuals. So they amended the Constitution immediately with the Bill of Rights, ten amendments that restricted what the government could do. It could not force people to practice a certain religion, restrict what newspapers wrote or people said, stop people from congregating peacefully, and so on. And that was the opening gambit in the attempt to use the United States government to protect individuals.

But by the middle of the nineteenth century, it seemed clear that a government that did nothing but keep its hands to itself had almost failed. It had allowed a small minority to take over the country, threatening to crush individuals entirely by monopolizing the country’s wealth. So, under Presidents Abraham Lincoln and Ulysses S. Grant, Americans expanded their understanding of what the government should do. Believing it must guarantee all men equal rights before the law and equal access to resources, they added to the Constitution the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments, all of which expanded, rather than restricted, government action.

The crisis of industrialization at the turn of the twentieth century made Americans expand the role of the government yet again. Just making sure that the government protected legal rights and access to resources clearly couldn’t protect individual rights in the United States when the owners of giant corporations had no limits on either their wealth or their treatment of workers. It seemed the government must rein in industrialists, regulating the ways in which they did business, to hold the economic playing field level. Protecting individuals now required an active government, not the small, inactive one the Framers imagined.

In the 1930s, Americans expanded the job of the government once again. Regulating business had not been enough to protect the American people from economic catastrophe, so to combat the Depression, Democrats under President Franklin Delano Roosevelt began to use the government to provide a basic social safety net.

Although the reality of these expansions has rarely lived up to expectations, the protection of equal rights, a level economic playing field, and a social safety net have become, for most of us, accepted roles for the federal government.

But all of those changes in the government’s role focused on men who were imagined to be the head of a household, responsible for the women and children in those households. That is, in all the stages of its expansion, the government rested on the expectation that society would continue to be patriarchal.

The successful pieces of Biden’s legislation have echoed that history, building on the pattern that FDR laid down.

But, in the second half of his Build Back Better plan—the “soft” infrastructure plan that Congress did not pass—Biden also suggested a major shift in our understanding of the role of government. He called for significant investment in childcare and eldercare, early education, training for caregivers, and so on. Investing in these areas puts children and caregivers, rather than male heads of households, at the center of the government’s responsibility.

Calls for the government to address issues of childcare reach back at least to World War II. But Congress, dominated by men, has usually seen childcare not as a societal issue so much as a women’s issue, and as such, has not seen it as an imperative national need. That congressional fathers are adding their voices to the mix suggests a shift in that perception and that another reworking of the role of the government might be underway.

This particular effort might well not result in anything in the short term—caucuses form at the start of every Congress, and many disappear without a trace—but that some of Congress’s men for the first time ever are organizing to fight for parental needs just as the Department of Labor says childcare costs are “untenable” strikes me as a conjunction worth noting.

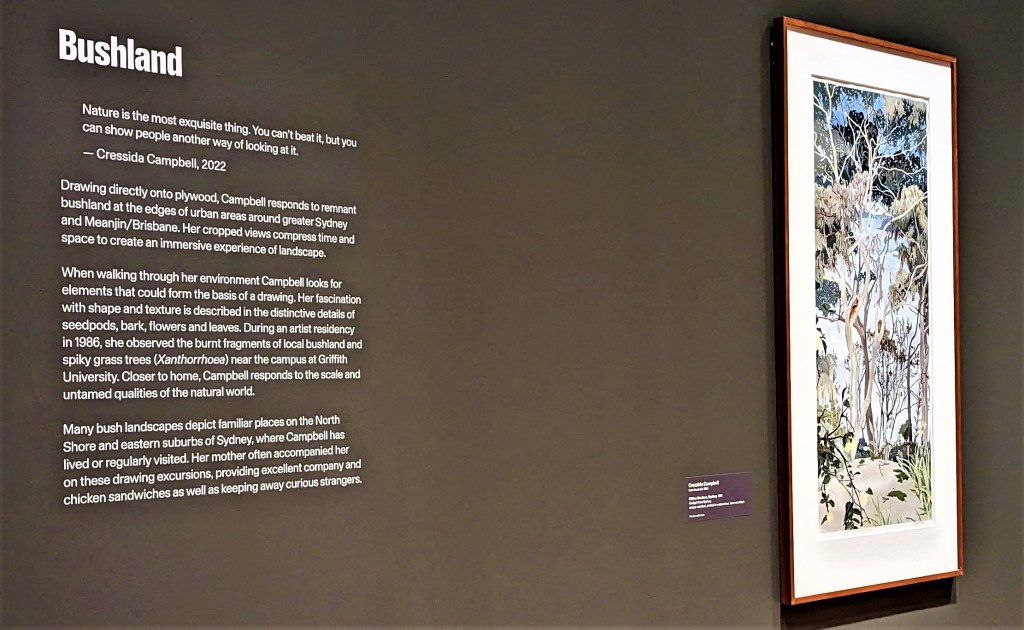

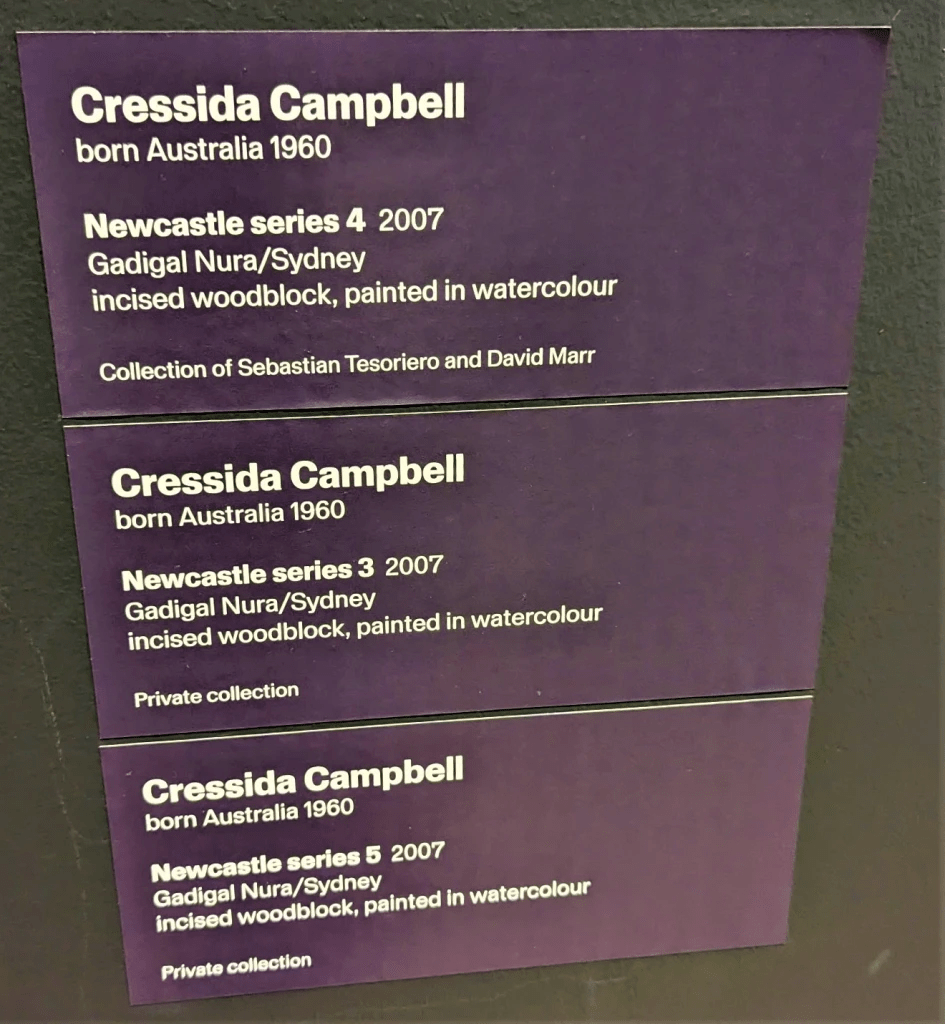

Cressida Campbell Exhibition at the National Gallery of Australia

A feature that provided a pleasant interlude while waiting to enter the timed exhibition, or afterwards, was the provision on sketch pads, pencils and displays to create one’s own artwork.

The exhibition was immense – with so many of Campbell’s works, ranging from self-portraits, interiors, flowers, the wonderful Australian veranda, and delightful Otto, a grey cat.

Otto on the Staircase, Cressida Campbell

Otto again – in a mirrored room

Self portraits

The Letter from America below refers to Phyllis Schlafly’s contribution to the original debate on Roe vs Wade.

Heather Cox Richardson Letters from an American

Tomorrow marks the fiftieth anniversary of the Roe v. Wade decision. On January 22, 1973, the Supreme Court decided that for the first trimester of a pregnancy, “the attending physician, in consultation with his patient, is free to determine, without regulation by the State, that, in his medical judgment, the patient’s pregnancy should be terminated. If that decision is reached, the judgment may be effectuated by an abortion free of interference by the State.”

It went on: “With respect to the State’s important and legitimate interest in potential life, the ‘compelling’ point is at viability. This is so because the fetus then presumably has the capability of meaningful life outside the mother’s womb. State regulation protective of fetal life after viability thus has both logical and biological justifications. If the State is interested in protecting fetal life after viability, it may go so far as to [prohibit] abortion during that period, except when it is necessary to preserve the life or health of the mother.”

The wording of that decision, giving power to physicians—who were presumed to be male—to determine with a patient whether the patient’s pregnancy should be terminated, shows the roots of the Roe v. Wade decision in a public health crisis.

Abortion had been a part of American life since its inception, but states began to criminalize abortion in the 1870s. By 1960, an observer estimated, there were between 200,000 and 1.2 million illegal U.S. abortions a year, endangering women, primarily poor ones who could not afford a workaround.

To stem this public health crisis, doctors wanted to decriminalize abortion and keep it between a woman and her doctor. In the 1960s, states began to decriminalize abortion on this medical model, and support for abortion rights grew.

The rising women’s movement wanted women to have control over their lives. Its leaders were latecomers to the reproductive rights movement, but they came to see reproductive rights as key to self-determination. In 1969, activist Betty Friedan told a medical abortion meeting: “[M]y only claim to be here, is our belated recognition, if you will, that there is no freedom, no equality, no full human dignity and personhood possible for women until we assert and demand the control over our own bodies, over our own reproductive process….”

In 1971, even the evangelical Southern Baptist Convention agreed that abortion should be legal in some cases, and vowed to work for modernization. Their convention that year reiterated the “belief that society has a responsibility to affirm through the laws of the state a high view of the sanctity of human life, including fetal life, in order to protect those who cannot protect themselves” but also called on “Southern Baptists to work for legislation that will allow the possibility of abortion under such conditions as rape, incest, clear evidence of severe fetal deformity, and carefully ascertained evidence of the likelihood of damage to the emotional, mental, and physical health of the mother.”

By 1972, Gallup pollsters reported that 64% of Americans agreed that abortion should be between a woman and her doctor. Sixty-eight percent of Republicans, who had always liked family planning, agreed, as did 59% of Democrats.

In keeping with that sentiment, in 1973 the Supreme Court, under Republican Chief Justice Warren Burger, in a decision written by Republican Harry Blackmun, decided Roe v. Wade, legalizing first-trimester abortion.

The common story is that Roe sparked a backlash. But legal scholars Linda Greenhouse and Reva Siegel showed that opposition to the eventual Roe v. Wade decision began in 1972—the year before the decision—and that it was a deliberate attempt to polarize American politics.

In 1972, President Richard Nixon was up for reelection, and he and his people were paranoid that he would lose. His adviser Pat Buchanan was a Goldwater man who wanted to destroy the popular New Deal state that regulated the economy and protected social welfare and civil rights. To that end, he believed Democrats and traditional Republicans must be kept from power and Nixon must win reelection.

Catholics, who opposed abortion and believed that “the right of innocent human beings to life is sacred,” tended to vote for Democratic candidates. Buchanan, who was a Catholic himself, urged Nixon to woo Catholic Democrats before the 1972 election over the issue of abortion. In 1970, Nixon had directed U.S. military hospitals to perform abortions regardless of state law, but in 1971, using Catholic language, he reversed course to split the Democrats, citing his personal belief “in the sanctity of human life—including the life of the yet unborn.”

Although Nixon and Democratic nominee George McGovern had similar stances on abortion, Nixon and Buchanan defined McGovern as the candidate of “Acid, Amnesty, and Abortion,” a radical framing designed to alienate traditionalists.

As Nixon split the U.S. in two to rally voters, his supporters used abortion to stand in for women’s rights in general. Railing against the Equal Rights Amendment, in her first statement on abortion in 1972, activist Phyllis Schlafly did not talk about fetuses: “Women’s lib is a total assault on the role of the American woman as wife and mother and on the family as the basic unit of society. Women’s libbers are trying to make wives and mothers unhappy with their career, make them feel that they are ‘second-class citizens’ and ‘abject slaves.’ Women’s libbers are promoting free sex instead of the ‘slavery’ of marriage. They are promoting Federal ‘day-care centers’ for babies instead of homes. They are promoting abortions instead of families.”

A dozen years later, sociologist Kristin Luker discovered that “pro-life” activists believed that selfish “pro-choice” women were denigrating the roles of wife and mother. They wanted an active government to give them rights they didn’t need or deserve.

By 1988, radio provocateur Rush Limbaugh demonized women’s rights advocates as “feminazis” for whom “the most important thing in life is ensuring that as many abortions as possible occur.” The complicated issue of abortion had become a proxy for a way to denigrate the political opponents of the radicalizing Republican Party.

Such threats turned out Republican voters, especially the evangelical base. But support for safe and legal abortion has always been strong. Today, notwithstanding that it was overturned in June 2022 by a Supreme Court radicalized under Republican presidents since Nixon, about 62% of Americans support the guidelines laid down in Roe v. Wade, about the same percentage that supported it fifty years ago, when it became law.

—

Notes:

https://news.gallup.com/poll/350804/americans-opposed-overturning-roe-wade.aspx

Linda Greenhouse and Reva B. Siegel, “Before (and After) Roe v. Wade: New Questions About Backlash,” The Yale Law Journal, 120 (June 2011): 2028–2087, at https://www.jstor.org/stable/41149586

https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/410/113

https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2022/05/15/abortion-history-founders-alito/