Christmas reading on the beach, with the occasional discomforts caused by sand, water and sun requiring a break; interruptions from enthusiasts who encourage venturing into the cold sea or the lure of a trip to buy fish and chips, is best served by some easily read fiction. Some of the following novels have been provided to me by NetGalley, and they have been reviewed. Others are my quick reads in between the more serious non-fiction NetGalley sends me.

Two NetGalley reads are reviewed below. The beach reads comments appear after the Covid update. Other articles are: Covering the World: What does Anne mean to readers the world over?; Christophe Premat, Napoleon; and Benjamin Neimark, How to assess the carbon footprint of a war.

Amanda Prowse Swimming to Lundy Lake Union Publishing, August 2024.

Thank you, NetGalley, for providing me with this uncorrected proof for review.

Lundy is an island off the coast of Tawrie Gunn’s home. She views it through the lens of her father’s drowning twenty years before this part of her story begins. Despite her father’s death continuing to influence her life, she joins the swimming Peacocks, a rather misnamed group of two whose regular swim becomes Tawrie’s way of changing her life, while maintaining contact with her father through talking to him while she swims. Twenty years before, Harriet is also living in the coastal town in which Tawrie, her parents and grandmother live at Signal House. Harriet has no roots in the town, unlike Tawrie and her family for whom Signal House is a home passed down through the Gunns. Harriet is writing a diary which explains why she, her unfaithful husband Hugo, and ‘Bear’ and ‘Dilly’, their children, have moved from their comfortable family home in a village to the Corner Cottage on the Devon coast. See full review at Books: Reviews.

Kerry Wilkinson The Ones Who Are Hidden (A Whitecliff Bay Mystery Book 4) Bookouture, May 2023.

Kerry Wilkinson has once again combined appealing continuing characters, Millie (and her son Eric, and divorced husband and his new wife) and Guy (and his nephew), with a new mystery that they must solve. At the same time, their stories are given more substance with each interaction between them and their family members. Some continuing stories reach resolution, cleverly associated with issue brought to the fore through the investigation, while new questions arise – hopefully, another book in the series will be written to resolve these. In the meantime, Kerry Wilkinson has begun writing other material (the Sleepover series) so we might have to wait. For me, the manner in which Wilkinson raises issues, and uses the continuing characters’ development as well as the new investigations to resolve these, is worth the wait. See Books: Reviews for the complete review. Also, the earlier books in the series reviews appear in posts for May 3, May 31 and August 3, 2023.

Covid update for Canberra

On 8 December there were 418 new cases with 11 people hospitalised, and none in ICU or ventilated. Three lives were lost.

Beach Reads

Sally Hepworth’s The Younger Wife (2022, Hodder and Stoughton) is a domestic drama which features dementia, kleptomania, inability to form relationships, alcoholism and incipient alcoholism, gaslighting and violence. Perhaps not fun beach reading, but certainly worth a read. The prologue is written in the first person, beginning that she is ‘a woman of a certain age…bland and forgettable’, always cries at weddings, has a knowledge of the family involved in the wedding, but is not close enough to any of them to be an invited guest, and ends with a scream and thud…

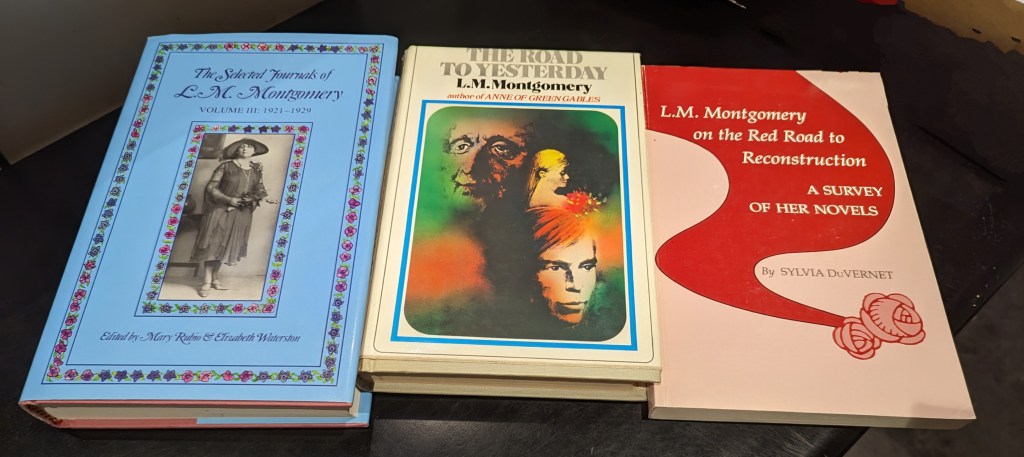

L.M. Montgomery’s birthday was celebrated on Facebook with some interesting discussions about her books. People of all ages commented on the books they love – and read and reread. Sylivia DuVernet (L.M. Montgomery on the Red Road to Reconstruction, 1993) makes the point that L.M. Montgomery writes for all ages. Most well-known is the Anne of Green Gables series, but many people preferred, as do I, the Emily of New Moon series. Standalone books that stood out in popularity were The Blue Castle (a study by Sylivia DuVernet, The Mystique of Muskoka, published in 1988 is referred to as a perceptive commentary of this novel, and one I would like to read) and Jane of Lantern Hill. Prince Edward Island was one of my dream destinations, and I was fortunate to be able to visit in the 1990s. Because of the recent posts I decided to indulge in childhood fantasies and reread some of her novels.

One of the features of the Anne books was the importance of retaining Green Gables, the farming property to which Anne arrived after time as a household help in unpleasant and often cruel, circumstances, and an unhappy period in an orphanage. As a young adult Anne puts aside her plans to ensure that Marilla can remain in her home. Jane of Lantern Hill and The Blue Castle also emphasise the value of property to women. Although couched in romantic language and ideas, L.M. Montgomery nevertheless has a serious regard for women’s attachment to particular houses, from the domestic role Jane wants to adopt, to the castle of Valancy’s dreams. Contrary to the women’s important role in the houses in the early Anne books and featured in Jane of Lantern Hill and The Blue Castle is Gilbert’s independent purchase of Ingleside in Anne of Ingleside. Here, the ideas associated with the traditional marriage between Anne and Gilbert replace the independence Montgomery gave young women in her other works.

Covering the World: What does Anne mean to readers the world over?

Excerpt from: L.M. Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables Manuscript is presented by the Confederation Centre of the Arts, the L.M. Montgomery Institute, and the University of Prince Edward Island’s Robertson Library. Funded by Digital Museums Canada.

Australia

Lisa Bennett and Kylie Cardell, Flinders University, South Australia

Before anything else, we both remember Anne wading thigh-deep through the snow. We live in Australia, but Lisa grew up in Canada. For her, snow was miserable and mundane; it was Anne’s heroism and magic that changed the wintry landscape forever. For Kylie, a girl from Brisbane, the romantic scenery of Anne of Green Gables, so lovingly rendered in Montgomery’s novel and pictured so unforgettably in Sullivan’s mini-series, was inconceivably fantastic—Anne’s desperate dash through the frozen landscape of a wintry night to act as nurse-hero to Diana’s baby sister might well have been a scene from science fiction for all its relevance to my reality. Reading through that scene, we are awash with nostalgia, hearts aglow. No matter where we are, Anne is there, different from how she was in our memories, but still doing the same thing she always did: wending her way through the Canadian landscape, unashamedly daydreaming, reciting lines from the literature that had changed her—and our—life.

Whenever—and wherever—we think of Anne, we are home. See Further Commentary and Articles about Authors and Books* for the whole article – for those who loved L.M. Montogomery books it is really worth reading.

Thank you to – The Anne of Green Gables Manuscript and Saved from L.M. Montgomery Literary Society’s post on Facebook for this wonderful contribution to knowledge about L.M. Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables.

Studies of L.M. Montgomery’s work make excellent reading, but perhaps not for the beach. Although, on second thoughts, I’m keen to reread Sylvia Du Vernet’s book pictured above.

Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Secret Garden is worth reading at any age.

But then, back to murder, domestic drama and mayhem in relationships, and social commentary in some Agatha Christie, Valerie Keogh, K.L. Slater, Lisa Unger, Kerry Fisher and Penny Bachelor. I can dip into a Barbara Pym novel any time that I want something just wonderful to read.

Photo: Agatha Christie’s library of various editions of her novels at Greenway.

Agatha Christies I pulled off the shelf include some of her less impressive works (although I could not possibly revisit Passenger to Frankfurt (1970) and Elephants Can Remember (1972)). Hallowe’en Party (1969) features Ariadne Oliver, portrayed as a slim American in the film purportedly based on this novel, A Haunting in Venice. Agatha Christie’s Oliver is of an age where she sits to rest her feet (even when probably clad in more sensible shoes than the recent film version), she dithers and ruminates, eats apples, is self-deprecating in her request for Poirot to assist in solving the murder of a schoolgirl at a party. The manner of her death, drowning in a bucket of apples which is part of the paraphernalia for the party games, makes a dramatic change to Oliver’s eating habits – she rejects apples forever. The story includes unpleasant manipulation of a young girl, a rather ugly love affair, and more deaths. Another that I shall not reread. Dead Man’s Folly (1960) is a smarter book, perhaps because it was written ten years before the novels referred to above. Ariadne Oliver and Hercule Poirot solve the mystery of the death of a young girl who is part of a murder mystery devised by Oliver, and the missing ‘lady of the manor’. The novel is set in Devon, at Agatha Christie’s home there, Greenway. Good reads are Towards Zero (1944) and A Murder is Announced (1950). Towards Zero features Superintendent Battle whose personal experience (a good story line in itself) helps him solve the murder of an elderly. wealthy woman in her large home while hosting her family and friends at a house party. The would-be suicide story line promotes a rather implausible romance, but indeed, why not? Perhaps Christie was keen to bring together both her personas (under Mary Westmacott she wrote works quite different from the murders she wrote). A satisfying read, with some good red herrings and interesting characters. A Murder is Announced is the cleverest of the novels I read in this period. Miss Marple solves this the murders that arise from an announcement that a murder will take place at Little Paddocks. Announced in the Chipping Cleghorn Gazette, various avid villagers with high expectations of drama, but surely not murder, at the given time. A man dies, but the assumption that the hostess was the proposed victim is adopted by the guests. She is determined not to be afraid and continues life as usual. Further deaths take place in this cunningly crafted novel. Worth rereading for its comic moments, portrayal of village life and characters, depiction of women’s friendships, and of course a difficult to solve murder (or two…).

The majority of K.L. Slater’s Husband and Wife (2023) is seen through the eyes of Nicola, wife of Cal, mother of Parker, grandmother of Barney. Her characterisation is so realistic that all the annoying features of the indulgent mother and wife, who offers assistance to the level of interference in her family’s life almost overcome her depiction as the sympathetic character at the heart of the novel. In the prologue Sarah, who has waited unsuccessfully for her date in the pub, leaves pondering whether she should use the short cut, does so and is murdered. The story then revolves around Parker and his wife Luna’s serious car accident, Nicola’s realisation that they are separating, a result of which could be she and Cal losing contact with their beloved grandson, and her finding an incriminating piece of evidence from the murder case. This is a fairly good beach read, with an unexpected resolution. K.L. Slater has written better novels, so is worth considering for this purpose. I recall being impressed with Blink (2017) and The Evidence (2021). The Bedroom Window, reviewed June 21, 2023, was disappointing, The Narrator, reviewed January 2023, is a satisfying read.

The Love Island (2015) is the second of Kerry Fisher’s published work. While it gives attention to the way in which two very different women are beguiled and controlled by their husbands, thereby giving it an element of social commentary, the novel is very much a romance. It has its funny moments as well as being a good study of relationships – between woman and men, women, and families. Kerry Fisher’s later novels, The Rome Apartment (2023) and Secrets at the Rome Apartment (2023) reviewed in the August 16, 2023, post are a better read and I look forward to the third in this series.

More beach reading will be covered in next week’s blog.

Napoleon

Christophe Premat’s article below is an excellent read, with its reflections on the role of historical accuracy in film, and legitimate concern with the value of looking closely at the narrative. This article is interesting reading also in conjunction with Eliot A. Cohen’s The Hollow Crown Shakespeare on How Leaders Rise, Rule, and Fall reviewed on August 30, 2023.

Republished under Creative Commons.

Published: December 9, 2023 1.55am AEDT

Christophe Premat Associate Professor in French Studies (cultural studies), head of the Centre for Canadian Studies, Stockholm University – Disclosure statement: Christophe Premat does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Napoleon: ignore the griping over historical details, Ridley Scott’s film is a meditation on the madness of power

While Ridley Scott’s Napoleon has been causing consternation among some historians, they are overlooking the fact that the historical record does actually support the film’s narrative in terms of one man taking power and shaping a new order during times of revolution and chaos.

Set against the bloody backdrop of the French revolution (1789-1799), Empress Josephine – a beautifully judged performance by Vanessa Kirby – who narrowly escaped Robespierre’s guillotine, loves Napoleon for his power and image.

In turn, the general (played by a much older Joaquin Phoenix – Napoleon at this point was 30, Phoenix is 49, but is so good it is easy to overlook this detail that had historians squawking), is obsessed with Josephine. The film unfolds in an unpredictable narrative, laying bare the poignant letters that expose the complex love/hate relationship they share.

But Napoleon’s Egyptian trip is interrupted by rumours of Josephine’s infidelity, compelling him to return home in secret. He justifies this with the need to monitor the turbulence that threatens the cohesion of France.

By illuminating Napoleon in different shades – sometimes as a passionate being devoted to his love for Josephine, and sometimes as a military genius leading his troops – Scott manages to bring us into the intimacy of power. This comes at a time when France faces the temptation to turn back the clock and deviate from its revolutionary ideals by restoring the ancien régime (the system of prior to the French Revolution).

Picking his moments

The film avoids descending into excessive carnage and instead maintains a fast pace with carefully chosen scenes. The intention is not to reproduce every detail of Napoleon’s life, but rather to present the powerful French general who captured the world’s attention for more than 15 years.

On the geopolitical front, the battle of Toulon was fought in 1793, where Napoleon surprised British troops by taking possession of their fleet. Then came the conquest of Egypt, whose scenes, no doubt exaggerated (such as the destruction of the pyramids and the opening of a sarcophagus), form part of Scott’s artistic interpretation.

When Napoleon’s hat rises above the corpse in the sarcophagus, it recalls Mozart’s Requiem – death slowly approaching in these carefully choreographed moments of destruction. The battle of Austerlitz is admirably rendered, with Napoleon’s memorable strategic manoeuvre outsmarting the enemy by making them think there was a weak point where he could attack.

By letting the enemy surround him on both flanks, Napoleon used the strategic advantage to fight superior opposing armies. He then meets Tsar Alexander I, portrayed by a young actor. Scott uses the age aspect to show the ambivalence of Napoleon’s relationship with power. Napoleon thinks he is dealing with a young tsar, less experienced and impressed by the large army.

The fact that they have a common enemy is not enough to unite them, and the director gives the viewer a powerful wink when Phoenix sits on the abandoned throne of Alexander I, a leader who preferred to burn his cities to starve the great army.

It is as if we have a second version of Scott’s Oscar-winning Gladiator here, with Napoleon as Emperor Commodus, unable to accept the rationality of reality and stubbornly stuck in a form of hubris that will claim the lives of more than 500,000 soldiers.

The “spirit of the world”, as the philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel called Napoleon, is now no more than a shadow of his former self, aware that death is never far away. Scott chooses to show us a man who, despite the exaggerations, is sincere and direct, capable of winning the respect of soldiers and leading them into difficult battles.

History and power

The film is rich in subtle nuances, alternating between the tragic, the farcical and the grotesque, as power often manifests itself in this paradoxical arena. Karl Marx, a keen observer of the upheavals in France, showed no hesitation in his book on Napoleon’s coup d’état in emphasising the tragic and comic recurrences in history.

A despot always creates successors, and history is found in parodic reincarnations. Napoleon III was, for instance, a pale replica of Napoleon I, losing most of his wars. In fact, Napoleon III tried to mimic the leadership style of Napoleon without being able to reconcile monarchist and republican forces. Although he succeeded in modernising the country, he never really established himself as a leading figure in the memory of the French people.

In Scott’s film, we can feel the postmodern hesitation between the old and the new world. Historically, Napoleon consolidated the gains of the Revolution, and the French are grateful to him for ending this phase. This prevented a complete return to the ancien régime, despite the illusions of the counter-revolutionary Restoration regime after the Congress of Vienna.

That is why this film is an absolute must-see. Through the fiction, sometimes surpassed by the brutal reality, the viewer is invited to immerse themselves in the madness of power and its irreversible impact on the fate of nations.

There is also an underlying appeal to not just read history to trace the past, but rather to understand the experience of power madness. Scott has undoubtedly created the film that Stanley Kubrick dreamed of making. Don’t miss it.

Jocelynne Scutt’s 10 December 2023 zoom meeting, BRILLIANT & BOLD – BOLD & BRILLIANT CONVERSATIONS WITH ‘ORDINARY’ & ‘EXTRAORDINARY’ WOMEN addressed the topic “Making Women’s Voices Heard – in Climate Change, Consent and Cooperating Globally”. The environmental impact of war was raised in the discussion. I was pleased to see the detailed discussion of the issue in the article below.

How to assess the carbon footprint of a war

Benjamin Neimark, Senior Lecturer, School of Business Management, Queen Mary University of London

Disclosure statement

Benjamin Neimark receives funding from UK Research and Innovation, Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) – Concrete Impacts Project.

Published: December 13, 2023 5.09am AEDT

Republished under Creative Commons.

We know that war is bad for the environment, with toxic chemicals left polluting the soil and water for decades after fighting ceases. Much less obvious are the carbon emissions from armed conflicts and their long-term impacts on the climate.

Colleagues and I have estimated that the US military alone contributes more greenhouse gas emissions than over 150 countries, but too often discussions of the links between militaries and climate change focus only on future risks to global security in climate-affected settings. There are many tepid attempts by militaries to green their war machines – developing electric tanks or navy ships run on biofuels – yet there is very little discussion of how they contribute to climate change, especially during war.

Militaries are not very transparent and it is extremely difficult to access the data needed to run comprehensive carbon emissions calculations, even in peacetime. Researchers are essentially left on their own. Using an array of methods, colleagues and I have been working to open this “black box” of wartime emissions and demand transparent reporting of military emissions to the UN’s climate body, the UNFCCC.

Here are some of the ways militaries create emissions, and how we go about estimating them.

Direct and indirect emissions

Some military emissions are not necessarily specific to wartime, but dramatically increase during combat. Among the largest sources are jet fuel for planes and diesel for tanks and naval ships.

Other sources include weapons and ammunition manufacturing, troop deployment, housing, and feeding armies. Then there is the havoc that militaries cause by dropping bombs, including fires, smoke and rubble from damage to homes and infrastructure – all amounting to a massive “carbon war bootprint”.

In order to account for all of this carbon, researchers must begin with basic data surrounding direct “tailpipe” emissions, known as Scope 1 emissions. This is the carbon emitted directly from burning fuel in the engine of a plane, for instance. If we know how much fuel is consumed per kilometre by a certain type of jet plane, we can begin to estimate how much carbon is emitted by a whole fleet of those planes over a certain amount of missions.

Then we have emissions from heating or electricity that are an indirect result of a particular activity – emissions from burning gas to produce electricity to light up an army barracks, for instance. These are Scope 2 emissions.

From there, we can try to account for the complex “long tail” of indirect or embodied emissions, known as Scope 3. These are found in extensive military supply chains and involve carbon emitted by anything from weapons manufacturing to IT and other logistics.

To understand combat emissions better, my colleagues have even proposed a new category, Scope 3 Plus, which includes everything from damage caused by war to post-conflict reconstruction. For example, the emissions involved in rebuilding Gaza or Mariupol in Ukraine will be enormous.

Concrete problems

Our most recent research, looking at the US military’s use of concrete in Iraq from 2003 to 2011, illustrates some of the calculations involved. During its occupation of Baghdad, the US military laid hundreds of miles of walls as part of its urban counterinsurgency strategy. These were used to protect against the damage caused by bombs planted by insurgents, and to manage civilian and insurgent movements within the city by channelling residents through authorised roads and checkpoints.

However, concrete also has a massive carbon footprint, accounting for almost 7% of global CO₂ emissions. And the concrete walls in Baghdad alone – 412km (256 miles) – were longer than the distance from London to Paris. Those walls caused the emission of an estimated 200,000 tonnes of CO₂ and its equivalent in other gases (CO₂e), which is roughly equivalent to the total annual car tailpipe emissions of the UK, or the entire emissions of a small island nation.

Ukraine war has the carbon footprint of Belgium

In Ukraine, colleagues have begun the colossal task of adding up all the above factors and more in order to calculate the carbon effects of Russia’s invasion. This work is revolutionary as it attempts to do the very difficult task of accounting for the emissions of war in almost real time.

These researchers estimate the carbon footprint of the first year of the war to be in the region of 120 million tonnes of CO₂e. That’s roughly the annual emissions of Belgium. Ammunition and explosives alone for around 2 million tonnes of CO₂e in that period – equal to almost 1 billion beef steaks (150g), or 13 billion kilometres of driving.

A focus on conflict emissions is particularly timely given the Ukraine and Israel-Gaza wars, but also because of draft legislation concerning the 27 legal principles on the protection of the environment in relation to armed conflicts (Perac) that was passed by the UN general assembly in December 2022. While Perac is a major step forward, it still has little to say about greenhouse gas emissions during conflict.

Governments should adhere to their obligations to transparent and accurate reporting of military emissions. People are beginning to link armed conflict, greenhouse gas emissions and environmental protection, but the topic remains under-reported and unresearched – it’s time to shine a spotlight on this hidden aspect of war.