In this week’s blog I review two books, The Artist’s Apprentice, historical fiction, and Tudor Feminists Ten Renaissance Women Ahead of Their Time, an account of ten noteworthy women in the Tudor period.

Rebecca Wilson Tudor Feminists Ten Renaissance Women Ahead of their Time Pen & Sword, Pen & Sword History, January 2024.

Rebecca Wilson’s Tudor Feminists Ten Renaissance Women Ahead of their Time does not display the lively writing which is one of the enduring features of Pen & Sword publications. However, this more densely written work certainly provides a fascinating read and is well worth Pen & Sword readers adapting to a different style. The description ‘feminist’ to introduce these ten women is something to think about. Were they feminist? Is feminism a broad or narrow term to be used in describing women and their behaviour? What behaviour is feminist? Could the period in which the women acted impact an understanding of whether that action was feminist or not?

All of these questions influenced my reading, making the book come alive as I read and pondered, not only the women’s behaviour and the period, but how I feel about what makes a woman’s behaviour feminist. Wilson’s reference to Well behaved women seldom make history by Laurel Thatcher Ulrich provides a valuable clue to how to read the book as a tribute to feminism and feminist behaviour in the Renaissance period, so well-known through the Tudors. She also clarifies in the introduction suggesting that her description of the women in her book as feminist rests on their challenge to the patriarchal world in which they lived, surviving in that world while remaining out of step with it and, of course, their being remembered. The latter is essential to recognising that because we know something about them they must have stood out over and above their being associated with the Tudors, however popular that period is as historical fare for fiction and non-fiction authors. See Books: Reviews for the complete review.

Clare Flynn The Artist’s Apprentice Storm Publishing, February 2024.

Thank you, NetGalley, for this uncorrected proof for review.

This is the first of Clare Flynn’s novels that I have read. There is a lot to admire, for example the range of political and feminist issues that are covered in this essentially romantic novel. However, although I found the novel a good read, engaging, with interesting characters, I cannot give the writing an entirely positive response. Despite that, I am pleased to have had the opportunity to read this example of this popular author’s work and would like to know what happens to the main protagonists in the follow up, The Artist’s Wife.

The novel begins in January 1908 at Alice’s home, Dalton Hall, in Surrey. Alice is sketching in the frost on her window and must take diversionary action so that her lateness to breakfast goes unnoticed. Taking in the mail to effect this, Alice is confronted with an envelope addressed in writing with that makes her uneasy. It is an invitation from the American born wife of a newly rich neighbour, Cutler, inviting them to tea. Lord Dalton is pleased; his wife, unaware of the financial reason for her husband’s enthusiasm, is not. Alice is wary. Her brother, Victor, supports his father – he has prospects of joining the profitable Cutler firm of stockbrokers. See Books: Reviews for the complete review.

Covid update: Australia

Governments have been steadily dismantling the COVID surveillance system, but is that a backward step?

By Casey Briggs

If you’ve tried to look up the number of COVID cases in your area recently, you may have found it a frustrating exercise.

The reporting frequency in states and territories has been slowing down, from daily to weekly, and now fortnightly or monthly.

On top of that, what do the numbers even mean now? And how many are being missed?

It’s been a long time since we were asked to get a PCR test at the slightest sign of a tickly throat.

Now, the vast majority of cases are going undiagnosed or unreported.

That degradation in data quality is visible for everyone to see, and it’s no surprise: it would’ve been a big ask for us to keep up the COVID surveillance effort of 2020 and 2021 forever.

Likewise, behind the scenes governments have been steadily dismantling many other elements of a surveillance system that we were so reliant on in the emergency period of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Some public health experts think it’s a shame that we’re apparently returning back to the pre-pandemic ways we handled respiratory disease, after we’ve learned so much.

Weekly forecasting of COVID-19 has ended

The most recent thing to be discontinued is a weekly series of forecasts and “situational assessment reports” for federal and state officials.

The federal government had been contracting a group of mathematical modellers across multiple institutions to produce it, and it was one of the key regular pieces of advice they received.

How scientists are protecting themselves from COVID

The forecasts gave assessments of the COVID situation, including estimates for the effective reproduction number and transmission potential in each state and territory.

But the government has decided not to continue with that work, and in December, the contract ended.

The health department says the forecasting was in place for the emergency response phase, and has been ended given that COVID-19 is no longer a “Communicable Disease Incident of National Significance”.

Professor James Wood from the UNSW school of population health was one of the researchers involved in the work. “I’m not surprised,” he says. “For some time, the government hasn’t been changing its decisions based on the epidemiological or modelling reports.

“Whether or not cases were going up might be of interest in terms of planning to some extent but … hospital capacity wasn’t being continuously strained and so on, so I think the value of it in the short term was less for government.”

It’s a return toward our pre-pandemic approach to respiratory disease, and that’s precisely the strategy: ministers and health officers have been saying for a long time that COVID is now being managed consistent with other communicable diseases like flu.

But some experts argue that we could use the lessons from COVID to do a much better job of tracking and managing flu than we did before.

“It does leave a gap in terms of epidemic intelligence … and what’s happening not only with COVID, but flu and RSV and probably in the next year or two, whooping cough as well will be one we’ll want to watch,” Professor Wood says.

In 2022 the US went through a “tripledemic“, where COVID, the flu and RSV all circulated simultaneously in high numbers.

The reality now is that when respiratory diseases are putting pressure on health systems, it won’t be because of a single pathogen. It could be several at once.

Have we missed an opportunity to make the most of what we’ve learned?

In the journal Emerging Infectious Diseases this month, a group of public health experts called it a “critical time” to review disease surveillance practices, suggesting an “integrated model of surveillance” that considers multiple respiratory viruses.

“Resuming pathogen-specific surveillance approaches, such as those for monitoring influenza, would represent a missed opportunity to build on learnings from emergency response efforts,” the authors wrote.

And ongoing surveillance is important if you want to catch emerging waves, new variants of concern, and entirely new pandemics early.

In order to monitor trends you have to monitor the inter-epidemic period as well the emergency period.

If you only stand things up when concerns arise overseas, you run the risk of acting too late.

The illness straining marriages until they crack

Professor Wood states it more clearly: “We don’t have a clear forward plan.”

“We’ve missed a little bit of an opportunity while COVID was in front of everyone’s minds to initiate more changes.”

The government says something is in the works, and that a National Surveillance Plan for COVID-19, influenza, and RSV is being developed.

“As part of this development process, a comprehensive review of national viral respiratory infection surveillance is being undertaken, including an assessment of current gaps in surveillance, potential novel and/or enhanced surveillance systems and data sources to fill these gaps, and the benefits and limitations of each,” the health department says.

“This will include an assessment of the cost-effectiveness and sustainability of population prevalence surveys within the Australian surveillance context.”

Professor Wood says this is all happening while COVID-19 continues to have a significant impact.

“Obviously, we’re very glad that it’s dropped from being something where we were worried about losing 100,000 lives a year in the initial phase, to 15,000 in the Omicron year to maybe 5,000 last year,” he says.

“It’s a lot better, but that’s still worse than flu, right?”

“I do think we have an opportunity here to take that a bit more seriously in terms of how we view it, how we measure it, and how we advise the community on how to deal with it.”

Other governments are investing heavily in disease forecasting. What’s Australia doing?

Outside Australia, governments have clearly recognised the value of forecasting in public health.

In the US, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention announced more than US$250 million over five years to establish a network of infectious disease forecasting centres.

That’s one of the actions of the CDC’s Center for Forecasting and Outbreak Analytics.

It was launched in 2022, directly in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The European Union’s equivalent to the American CDC, the ECDC, also launched a respiratory forecasting program late last year.

It shows how other countries are investing in the intelligence that they saw had value through the pandemic, and seemingly prioritising it more than Australia.

The Australian government is in the process of setting up a CDC here. It exists in interim form right now, with staff recruitment expected to happen this year.

That body may have some role in respiratory forecasting, but it is still in its infancy.

The health department says it is now focusing on “the adoption of novel and cost-effective surveillance strategies, with a reduced focus on case notifications”.

“The use of sentinel surveillance, healthcare utilisation data, genomic sequencing, and wastewater analysis will allow us to shift our surveillance approach to a more sustainable and integrated system that is more appropriate to the current epidemiological situation,” the department said in response to the ABC’s questions.

Wastewater analysis was one of the big new developments of the COVID pandemic, but Professor Wood says there’s a bit of work to do before we can rely more heavily on it.

“Tools like wastewater or some of the surveys like flu tracking may be promising ways to do this, but they haven’t been validated,” he says.

“And until we invest in doing some actual prevalence surveys and comparing with a known technique where we know the percentage positive and so on, we’re not really confident that this is actually consistently a good measure.

“We don’t know. There’s been some slightly weird results to wastewater in Europe in the most recent wave.”

In the meantime, modellers and public health experts plan to continue some of their work.

“Myself and others in Australia are going to continue to do some forecasting this year,” Wood says.

“But we have to set up new data agreements with state carriers, we have to rely on them being interested, and we’ll have to find some way to make this something we can continue to fund.”

Posted 4 February 2024, ABC website.

From: The New Yorker January, 2024.

Illustration by Katharina Kulenkampff

Trials of the Witchy Women

Across seven centuries, women have been accused of witchcraft—but what that means often differs wildly, revealing the anxieties of each particular society.

By Rivka Galchen January 15, 2024

King James—he of the Bible—thought that drowning was the best test of witchcraft.

In 1532, when the Constitutio Criminalis Carolina became the law of the Holy Roman Empire, it specified that witchcraft was a serious crime, punishable by execution by fire. The Carolina was often cited in the European witch trials that followed, with crazes peaking in the second half of the sixteenth century, and again in the early decades of the seventeenth century. In Germany alone, twenty-five thousand people were executed. The Carolina is sometimes called the basis for these witch hunts, but it can also be seen as an attempt to tame them. Previously, trials could proceed on the allegations of only one accuser; the new set of laws required two. The accusers had to be deemed credible, and they could not be paid or of evil repute. There also had to be sufficient indication of sorcery for the accused to be tortured.

The Carolina was an improvement over trial by ordeal, which for centuries had been a fairly standard practice. In one common example, a suspected witch was forced to hold a burning iron; how quickly God healed the wound was the measure by which the accused was declared innocent or guilty. In 1597, King James VI of Scotland (he later became King James I of England—and of the Bible) wrote “Daemonologie,” in which he enthusiastically embraced witch-hunting. His ideas were not aligned with those behind the Carolina. He remained faithful to the floating ordeal—tossing suspects into the sea, where only the innocent, presumably, would sink. He described it as “perfect,” because “water shall refuse to receive them in her bosom, that have shaken off them the sacred Water of Baptisme.” Drowning was reserved for the saved. Compared with such ordeals, the Carolina begins to look progressive. It connects to the dream that the law, if written well, can save us from our worst selves, that it can temper passion with reason and reduce violence rather than codify it. Though things don’t always work out that way.

Marion Gibson, a professor of Renaissance and magical literature at the University of Exeter, has now written eight books on the subject of witches, including “Witchcraft Myths in American Culture” and “Witchcraft: The Basics.” Her eighth book, “Witchcraft: A History in Thirteen Trials” (Scribner), traverses seven centuries and several continents. There’s the trial of a Sámi woman, Kari, in seventeenth-century Finnmark; of a young religious zealot named Marie-Catherine Cadière, in eighteenth-century France; and of a twentieth-century politician, Bereng Lerotholi, in Basutoland, in present-day Lesotho. The experiences of the accused women (and a few accused men) are foregrounded, through novelistic descriptions of their lives before and after their persecution. Gibson describes, for example, Joan Wright working in the “cold hush” of her employer’s dairy, churning milk so that “fat globules rupture and coalesce” in the “near-magical transformation of cream into butter.” The inevitable charisma of villainy makes the accusers vivid as well. The character that I found myself following most attentively, however, is also the book’s through line: the trial.

“The Return of Martin Guerre,” by Natalie Zemon Davis, is built around the historical trial of Arnaud du Tilh, who for years successfully pretended to be the peasant Martin Guerre. “The peasants, more than ninety percent of whom could not write in the sixteenth century, have left us few documents of self-revelation,” Davis writes. “But there exists another set of sources in which peasants are found in many predicaments”—it is in court cases that we can catch sight of the hopes and emotions and fears of those who leave no other written record. The trials of the accused people in “Witchcraft” return to us, in detail, lives about which we might otherwise know nothing.

In what ways have varying legal codes and trial procedures altered the destinies of those accused of witchcraft? Although thirteen trials can’t decide the question, the book does put it on the stand. Gibson shows us church courts, state courts, colonial courts, assize courts, and improvised court systems used in the chaos of a civil war, and there are judging panels of three and judging panels of twenty-five. (And historically there were no judges or jurors who were women.) There are also the kinds of trial that happen outside a courtroom: trials by poison, and King James’s favored trial by “swim.” To wager on the outcome of these various trials is not as easy as you might think. They always seem to be hurrying to doom, but they occasionally don’t get there.

In 1645, in Manningtree, England, a tailor goes to a diviner, because his wife is having violent fits that are, he says, “more than merely natural.” The diviner confirms the man’s fears: two women have bewitched his wife. This is how Bess Clarke, a one-legged unmarried woman, came to be arrested and tried. Clarke’s mother had also been tried as a witch, years earlier, and executed. At the time of Clarke’s trial, the English Civil War had left the court system in disarray. Rather than being tried in an assize court, whose judges tended not to be very religious, Clarke was tried by a presiding judge who was a strict Puritan, a slave-trafficker, and a notoriously cruel admiral. Clarke faced a procedure called “watching and walking”: she was made to walk continuously around in her cell for four days, while observers noted whether any of her animal “familiars” or other devilish alliances come by to consult with her.

After Clarke became exhausted, she told her watchers that, if they would sit down with her, she would introduce them to her spirit animals. The watchers reported seeing several familiars, including a short-legged and plump “imp like unto a dog” that was white with sandy spots. One watcher said that this dog was the first spirit animal to appear, while another said that the first was a white cat named Hoult. There was also a long-legged greyhound named Vinegar Tom, a black rabbit called Sacke and Sugar, and a polecat. The animals were seen vanishing and transforming, and Clarke, in supplying her persecutors with the story of her seduction by Satan, said that they had been born from a fall into sin. Clarke is said to have referred to all the spirit animals as her “children”—and she did have a child at home, Jane, whom she had had baptized, and whose father had not married her.

In the ensuing trial, Clarke was not allowed representation, and her accusers were not cross-examined. The jury delivered a guilty verdict within minutes. She was sent to the gallows. Another convicted woman died while waiting in line to be hanged, perhaps from a heart attack. This did not stop the proceedings, and Clarke was killed that day.

What kinds of crime did people need to ascribe to witches? The Carolina punished only crimes that had caused others damage, but many women were charged with less tangible evils, such as attending a witches’ Sabbath or changing form. Some witches were said to have cursed brides, some to have caused storms to sink ships, some to have sailed to sea in a sieve, and quite a few to have effected the death of a baby. In a 1591 treatise, Johann Georg Gödelmann, a legal scholar who favored the regulations of the Carolina—and thus can be seen as relatively progressive for a witch expert of that time—argued that controlling the weather was not a real phenomenon, and therefore could not be the basis for legal questioning. He worked to separate people who had delusions—but were not actually witches—from what he saw as a quite small number of people who really did perpetrate evil, who really had made pacts with the Devil.

Torture produced wild tales of evil, of course. But even the monstrous and incredible forced confessions were often still personal; the accused sometimes told of what had really happened to them, indirectly. Kari, the Sámi woman, who was tried in Finnmark in a Danish colonial court, described the Devil taking the form not of a local animal, such as a reindeer, but of a goat, a non-native animal associated with the colonizer. When Bess Clarke confessed to having sex with the Devil, her description of him was reminiscent of the man who had impregnated her. Tatabe, an enslaved woman in Salem, Massachusetts (depicted in “The Crucible,” by Arthur Miller), was accused of bewitching two young girls. When pressed under torture to name her collaborators, she described one as “a tall man of Boston” in fancy clothes. She also said the other witches told her that, if she didn’t do what they said, they would hurt her, or even that her head would be cut off. Tatabe had most likely been sold into slavery as a child and sent to a plantation before spending a decade in Boston—she populated her confession with descriptions of people and situations we assume she encountered in her real life.

See also: Review of John Callow The Last Witches of England A Tragedy of Sorcery and Superstition Bloomsbury Academic 2022, published in my blog of October 26, 2023.

Anthony Albanese

Post to Facebook, 4 February 2024.

Lowitja O’Donoghue was one of the most remarkable leaders this country has ever known. As we mourn her passing, we give thanks for the better Australia she helped make possible.

Dr O’Donoghue had an abiding faith in the possibility of a more united and reconciled Australia. It was a faith she embodied with her own unceasing efforts to improve the lives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, and to bring about meaningful and lasting reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australia.

Life threw significant challenges at her – not least a childhood in which she was separated from her family, her language, and even her own name. From the earliest days of her life, Dr O’Donoghue endured discrimination that would have given her every reason to lose faith in her country. Yet she never did.

Dr O’Donoghue was a figure of grace, moral clarity, and extraordinary inner strength.

She was like a rock that stood firm in the storm – sometimes even staring down the storm. More than anything, she was one of the great rocks around which the river of our history gently bent, persuaded to flow along a better course.

With an unwavering instinct for justice and a profound desire to bring the country she loved closer together, Dr O’Donoghue was at the heart of some of the moments that carried Australia closer to the better future she knew was possible for us, among them the Apology to the Stolen Generation and the 1967 referendum.

She provided courageous leadership during the Mabo debates and as chair of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission.

Dr O’Donoghue knew that our best future was a shared one built on the strong, broad foundations of reconciliation. As she put it when she was made Australian of the Year, “Together we can build a remarkable country, the envy of the rest of the world.”

Throughout her time in this world, Dr O’Donoghue walked tall – and her example and inspiration made us all walk taller.

Now she walks in another place. Yet thanks to all she did throughout her long and remarkable life, she will always be around us.

Revered Australian Aboriginal rights activist Lowitja O’Donoghue dies aged 91

Story by Maroosha Muzaffar • 21h THE INDEPENDENT

GettyImages-79728914.jpg© AFP via Getty Images

Revered aboriginal rights activist Lowitja O’Donoghue – described as “one of the most remarkable leaders” Australia has ever seen – has died in Adelaide. She was 91.

In a statement, her family said: “Our Aunty and Nana was the Matriarch of our family, whom we have loved and looked up to our entire lives.“We adored and admired her when we were young and have grown up full of never-ending pride as she became one of the most respected and influential Aboriginal leaders this country has ever known,” Deb Edwards, O’Donoghue’s niece, said in the statement.

Her family said that she died in the Kaurna Country in Adelaide.

A Yankunytjatjara leader and activist, O’Donoghue was much loved for her remarkable contributions to the rights and well-being of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Australia.

Prime minister Anthony Albanese paid tribute to her lifelong dedication to advocating for indigenous rights. He said O’Donoghue was “one of the most remarkable leaders this country has ever known”.

“With an unwavering instinct for justice and a profound desire to bring the country she loved closer together, Dr O’Donoghue was at the heart of some of the moments that carried Australia closer to the better future she knew was possible for us, among them the Apology to the Stolen Generation and the 1967 referendum,” he added.

“She provided courageous leadership during the Mabo debates and as chair of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission.”

Former Senator Pat Dodson also remembered her and noted that “her leadership in the battle for justice was legendary.

“Her intelligent navigation for our rightful place in a resistant society resulted in many of the privileges we enjoy today.”

O’Donoghue’s family said her legacy would continue through the Lowitja O’Donoghue Foundation, which was created on her 90th birthday.

“Aunty Lowitja dedicated her entire lifetime of work to the rights, health, and wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples,” they said.

“We thank and honour her for all that she has done — for all the pathways she created, for all the doors she opened, for all the issues she tackled head-on, for all the tables she sat at and for all the arguments she fought and won.”

Lowitja Institute’s patron Pat Anderson AO described her as an outstanding leader and visionary whose story is one of great courage, integrity and determination.

“Lowitja was a national treasure,” Ms Anderson said. “She lived a remarkable life and made an enormous contribution to public life in pursuit of justice and equity for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and Indigenous people across the globe.

“Courageous and fearless in leading change, Lowitja was continually striving for better outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. She will remain in my heart as a true friend and an inspiration to Australians for years to come.”

O’Donoghue was the founding chairperson of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC) and played a key role in drafting the Native Title legislation that arose from the High Court’s historic Mabo decision, according to the foundation website.

She was named 1984 Australian of the Year and was the ï¬rst Aboriginal person to address the United Nations General Assembly and the ï¬rst Aboriginal woman to be appointed as a Member of the Order of Australia (AM).

Minister for Indigenous Australians Linda Burney also paid tribute to her “remarkable legacy”, and described her as a “fearless and passionate advocate” for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians.

“She was a truly extraordinary leader. Lowitja was not just a giant for those of us who knew her, but a giant for our country,” the minister said. “My thoughts and sincere condolences to her family.”

O’Donoghue, born to an Indigenous mother and a pastoralist father in South Australia, faced early childhood trauma when she and her sisters were removed from their mother at age two, growing up in Colebrook Children’s Home without reuniting with their mother for thirty years.

She became the first Aboriginal trainee nurse at Royal Adelaide Hospital, and later a pioneering leader as the first Aboriginal woman to hold significant positions including a regional director in an Australian federal department, the founding chairperson of the National Aboriginal Conference, and the first Aboriginal woman awarded the Order of Australia in 1977.

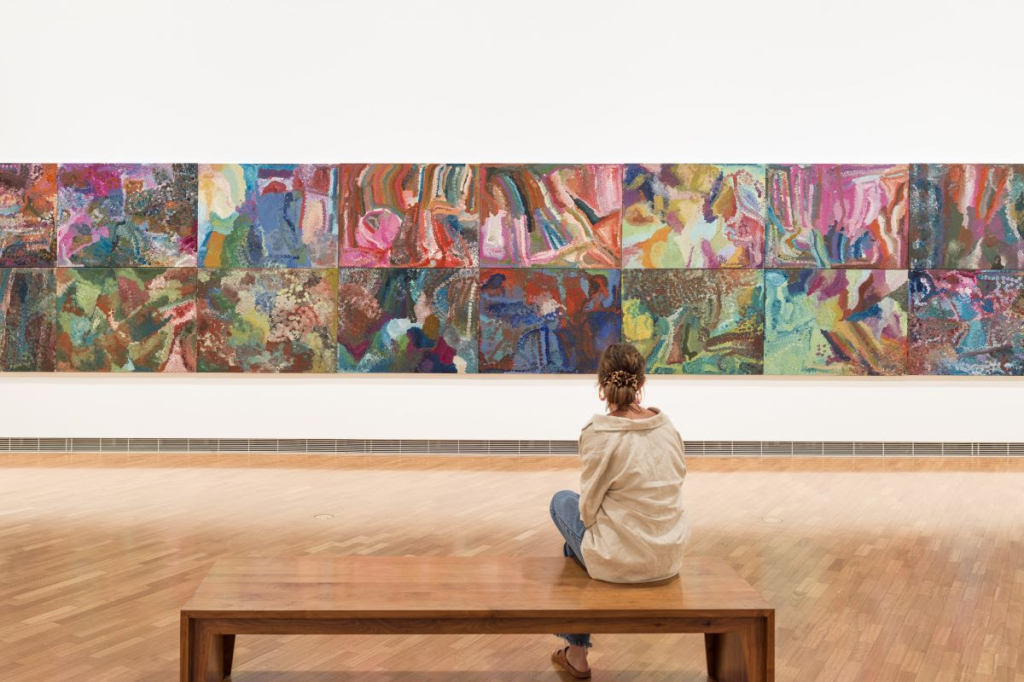

EMILY KAM KNGWARRAY

Until 28 Apr | Ticketed

As the sun sets on summer holidays, let Emily Kam Kngwarray’s vibrant art and deep cultural connections transport you to Country. The feeling of inspiration will stay with you long after you leave the Gallery.

‘Kngwarray’s work transcends time, inviting audiences to explore the spiritual landscapes and ancestral narratives woven intricately within each stroke.’

Dr Nick Mitzevich, National Gallery Director

Guided exhibition tours daily at 11.30am and 1pm. Free with exhibition ticket.

Access our free audio guide for a deeper understanding of Kngwarray’s works (simply bring your own device and headphones).

Specially designed for kids, our free art trail brings the exhibition to life with fun and playful activities.

Kids & Families

For Kids & Families: Emily Kam Kngwarray

At the Gallery

Sat and Sun

6 Jan – 28 Apr 2024

Temporary Exhibition Gallery, Gallery 12 (Level 1)

Wheelchair Accessible

ART CART: LEAF GAME

Sat 2 Dec 2024, 11am – 4pm (Special Opening Weekend Event)

Sat and Sun, 6 Jan – 28 Apr 2024, 10am – 2pm

Daily during school holidays, 15–29 Jan 2024 and 13–28 Apr 2024

Join National Gallery staff in the exhibition foyer to learn about Emily Kam Kngwarray’s art and Country through stories, play, creative activities, and games such as the Leaf Game, a storytelling game using sand and leaves, which is played by members of the Utopia community and was played by Emily Kam Kngwarray as a child.

Children must be accompanied by a parent/carer. This program is designed for children up to 8 years.

Located in the exhibition foyer

Free, drop-in, limited capacity

KIDS & FAMILIES ART TRAIL

Collect a free Kids & Families Art Trail when you visit the Emily Kam Kngwarray exhibition.

Inspired by Emily Kam Kngwarray’s life on Alhalker Country, the art trail invites children and their families to look at Emily Kam Kngwarray’s art together in the exhibition.

For more information about Kids & Families programs visit our dedicated Kids & Families page

The children’s art programs described above are such a change from the immediate past at the NGA. I am so pleased that the NGA is again catering for children’s artistic needs.