Two books are reviewed this week, The Artist’s Wife, fiction, and the non-fiction, Miss Dior. The latter ties into an article about a new television drama, The New Look, about Christian Dior.

Clare Flynn The Artist’s Wife (Hearts of Glass Book 2) Storm Publishing February 2024.

Thank you, NetGalley, for providing me with this uncorrected proof for review.

The Artist’s Wife reintroduces the story of several British families whose behaviour and activities continue to raise the social issues of the time. Although in the early part of the book domestic and romantic issues largely push out the intense and varied social commentary that was an excellent feature of Hearts of Glass Book 1, The Artist’s Apprentice, there is enough to ensure that this novel retains what I found appealing in the first, the social history of the time.

Two families are at the heart of the novel: Alice’s father, mother and brother, Lord and Lady Dalton and Victor, and Edmund’s father, Herbert Cutler. Connected to him is Dora, and her and Edmund’s daughter, Charlotte. Peripheral continuing characters are Christopher Whall, the stained-glass artist and Dora’s friend, Stanley Spinedellman. Alice’s aunt Eleanor and her husband, the Reverend Walter Hargreaves have continued to befriend the couple. Harriet and Lord Wallingford, the former Alice’s childhood friend also feature. As a background to the family dramas, young men leave for war, are mourned, and return needing nursing care in requisitioned accommodation. See Books: Reviews for the full review.

Justine Picardie Miss Dior Farrar, Straus and Giroux, NY, 2021

Thank you, NetGalley, for providing me with this uncorrected proof for review.

Justine Picardie suggests that this is the story of Catherine Dior, a ghost who would not let her be free, and thus becoming the focus of the book, Miss Dior. Although there are gripping allusions to some of the turmoil and horror of the life Catherine Dior must have led as a member of the French Resistance, and prisoner in Ravensbruk; her intermittent appearances in Christian Dior’s personal and fashion world; and reflections on her own post war world as she gathered together her ideas, fortitude and determination to follow her earlier interest in flowers and gardens it is difficult to do more than see glimpses of a woman whose life was so markedly different from that of her much older and public brother, Christian.

Some of the writing is wonderfully evocative, the garden with which the narrative begins is beautifully envisioned, and this beauty appears when appropriate throughout the work. There is little doubt that Picardie wanted to evoke Catherine rather than Christian, but it is all too easy to write of fashion, success, the powerful and socially important people who adored Christian and his fashions, and I feel that this is what has happened in this book. See Books: Reviews for the complete review.

After book reviews: Marion Halligan by Gillian Dooley; Apple TV Drama about Christian Dior; Docklands Film Studio – Green policy; Forgetting – Alexander Easton; Review of Merle Thornton’s autobiography; Cindy Lou; Labour by-election wins; research project on some reading during the 1950s.

The Conversation

Published: February 21, 2024 11.40am AEDT

Article below republished under Creative Commons Licence.

Gillian Dooley is an Honorary Senior Research Fellow in the Department of English at Flinders University. She was founding general editor of the Flinders Humanities Research Centre’s electronic journal Transnational Literature and founding co-editor of Writers in Conversation. She is a regular book reviewer for various journals and magazines, including Australian Book Review (edited from The Conversation).

Marion Halligan was a woman of great warmth and generosity, and a consummate novelist

Marion Halligan, who died on February 19 at the age of 83, was one of Australia’s finest authors. She has more than 20 books to her credit, including novels, short story collections and non-fiction. Her novels are compulsively readable and full of ideas.

Halligan was born and raised in Newcastle, but for most of her life she lived in and wrote about Canberra. She conveyed a strong sense of the place, with Lake Burley Griffin at the centre, “cool and severe and beautiful” as she described it in her 2003 novel The Point.

I interviewed Halligan about The Point for Radio Adelaide and later published the interview in Antipodes. She was audibly taken aback when I likened her work to that of the great British novelist Iris Murdoch. Although she admitted being an admirer of Murdoch, she had not thought of her as an influence.

But for me the resemblance was striking. What I saw was not imitation, but a shared attitude to the capacity of novels to explore the big questions of life, without sacrificing their readability. In our interview, Halligan said:

It seems to me that novels are very much about this question of how shall we live, not answering it but asking it, and what novelists do is look at people who live different sorts of lives, and often people who live rather badly are a good way of asking the question.

Another attribute Halligan shared with Murdoch was the richness of her web of allusions. In Halligan’s case, this was formed from the multitude of cultures and histories that make up Australian life in the 21st century. Her characters are embedded in their worlds. She said that she believed in giving her readers

a whole lot of concrete things to hang on to. […] Lakes and trees and food and maybe buildings. […] Then when you’ve done that you can come in with the ideas and abstract things, the unconcrete things, the emotions, and people will trust you.

Halligan never wrote the same novel twice. The Point is particularly Murdochian in its structure and tone. Lovers’ Knots (1992) is a historical novel, covering a century of family stories. The Apricot Colonel (2006) and its sequel Murder on the Apricot Coast (2008) are witty novels in the “whodunit” vein, playing with the familiar formula in clever ways.

Unlike many novelists, Halligan also wrote excellent short stories, publishing five collections. Intriguing and mordant, always intelligent, the stories in collections such as The Hanged Man in the Garden (1989) and Shooting the Fox (2011) are well worth revisiting.

Halligan suffered much heartache in her personal life and wrote about it directly in fiction and memoir. Her novel The Fog Garden (2001) was written after the death of her first husband. It is a moving tribute to a beloved partner, and a searching and honest account of adjusting to life without him.

I recall her telling me that it was a novel she needed to write, so she put her other projects on hold until it was done.

Halligan’s last book, Words for Lucy, published in 2022, was written for her daughter, who died in 2004.

A unique contribution

A consummate novelist and a brilliant wordsmith, Halligan was also a woman of great warmth and generosity. I met her several times. I visited her home in Canberra and partook of her hospitality. That she was an advocate for “slow food” – not necessarily complicated food, but “food with attention paid” – was obvious.

Her kitchen was large and welcoming, replete with wonderful aromas. Her non-fiction book The Taste of Memory (2004) celebrated food and its part in our lives and networks of love and memory.

Reviewing The Apricot Colonel in 2006, I wrote that “in Marion Halligan’s world, a male character who bottles apricots, chargrills vegetables, and speculates about the derivation of the word ‘idyll’ is never going to be a villain”.

There are not many generalisations that could be made about her, but I stand by this one.

Marion Halligan was a unique contributor to Australian literature and culture. She served as chair of the Literature Board of the Australia Council and received numerous awards for her writing, including the ACT Book of the Year, which she won three times. In 2022, the ACT Writers Centre was renamed Marion in recognition of her literary achievements and active support of local writers.

She was made a Member of the Order of Australia (AM) in 2006 “for service to literature as an author, to the promotion of Australian writers and to support for literary events and professional organisations”, Halligan has nevertheless not yet been the subject of a book-length study, unlike many novelists of her generation.

I commented in our interview that readability seems somewhat disreputable among literary scholars, and we agreed that was strange – and regrettable.

Halligan wrote movingly about death and dying, about loving and losing. She suffered the loss that we now suffer, losing her. She will be missed.

The New Look: Apple TV drama shows how Dior brought optimism to a war-weary world

Published: February 15, 2024 1.13am AEDT

Author Elizabeth Kealy-Morris

Senior Lecturer and Researcher in Dress and Belonging, Manchester Fashion Institute, Manchester Metropolitan University

Elizabeth Kealy-Morris does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Republished under – Creative Commons Licence.

Christian Dior’s 1947 “new look” – a collection of extravagantly brimmed hats, wide full skirts and cinched waists that drew attention to the female silhouette – signalled a new post-war era of optimism, pleasure and a sense of life returning to normal.

Dior’s haute couture collection remains a historical moment for post-war fashion, and lends its name to Apple’s new ten-part series. The drama explores the state of Parisian couture in the final year of the second world war and the years that followed through the lives of important designers. This includes Dior and his contemporaries Coco Chanel, Pierre Balmain, Cristóbal Balenciaga, Lucien Lelong, Hubert de Givenchy and Pierre Cardin.

Inspired by true events, the series stars Ben Mendelsohn as Dior, Maisie Williams as his younger sister Catherine, Juliette Binoche as Chanel, John Malkovich as Lelong and Glenn Close as the US Harper’s Bazaar fashion editor Carmel Snow.

The series begins in the wake of Dior’s huge success with the launch of his new look collection in 1947 with a Q&A at Sorbonne University in Paris. After a riotous welcome from an audience of fashion students, the Frenchman explains: “For those who lived through the chaos of war, creation was survival.”

This is the theme of the series, revealed in flashback: how the destruction and horror of war affected the world-renowned Parisian fashion market – its designers, design houses, those who worked within the industry and the people of France themselves.

A central character on and off screen is Dior’s courageous sister Catherine, who is little known and rarely mentioned in the history of Dior’s life, beyond the naming of his perfume Miss Dior in her honour in 1947. Throughout the series her fate is emblematic of the French population’s experience of occupation, and is depicted as the driving force of Dior’s dedication to couture.

French fashion during wartime

In June 1940, Nazi forces took control of northern and western France and its textile industry. By November 1942 the remainder of southern and eastern France fell to the German army.

Prior to the occupation, many non-French designers, such as Elsa Schiaparelli, left the country for London, New York and Los Angeles in anticipation of war. Once Nazi forces invaded, Paris and its international fashion markets were effectively cut off from the rest of the world.

The couturier Lucien Lelong occupies an important place in the series as Dior’s supportive employer – although much more could have been made of the key role he played in keeping Parisian couture open for business. “Creation cannot stop the bullets but creation is our way forward”, the character states. True to his word, as war raged, Lelong employed some of the most successful post-war designers in his atelier including Dior, Pierre Balmain and Hubert de Givenchy.

Lelong was elected president of the prestigious Chambre Syndicale de la Couture in 1937, and faced down threats from the Nazis to move the entire couture industry to Berlin and Vienna. He negotiated, persuaded and outmanoeuvred the Germans throughout the war by insisting that couture – and the domestic textile industry it depended on – was uniquely French and therefore could not be replicated elsewhere.

The couture industry experienced severe rationing of fabric. But the series successfully demonstrates that Paris fashion continued with determination and innovation. As fashion designers were forced to limit the amount of material they used, unnecessary decorative additions such as ruffles and pockets became expendable. Instead, wartime couturiers turned to embroidery and beading for decoration – trends that continue to characterise haute couture today.

The rival ‘American look’

With the end of the war and freedom from Nazi occupation, Paris fashion was in a fight for its life. Its biggest rival was the American ready-to-wear apparel industry, an aspect of the story this new series dramatises to great effect.

Though the American industry also faced fabric rationing during the second world war, it was not occupied, and the restrictions weren’t as debilitating. While Asian silks and Italian wools were no longer available, good American cotton was plentiful.

A new generation of American designers came into their own with a homegrown design aesthetic. In 1945 Dorothy Shaver, vice-president of the luxury retailer Lord & Taylor, developed a marketing campaign around the phrase “the American look”. This successfully encouraged American women to remember their roots and not return to the collections of the newly liberated Paris fashion houses.

Dior’s beacon of hope

Dior’s 1947 Carolle collection, was renamed the “new look” at first viewing by American fashion editor Carmel Snow. Snow claimed it represented the creation of a new femininity – which Dior would later call “the golden age of couture”.

It stood in stark contrast to the austerity wardrobes of wartime Europe and America – wardrobes millions of women around the world would continue to wear in everyday creative adaptations and alterations for years to come.

In my view, leaving the proper substance of the new look story until episode eight of a ten-part series suggests a lack of balance, and makes the title of the drama feel a little misleading. Despite the voice-over in the trailer saying so, Dior’s new look did not reinvent fashion. Rather, it celebrated the end of the grim years of wartime trauma, misery and lack.

What Dior did through his collection was usher in a sense of optimism that women could once again enjoy the pleasure of pretty, feminine clothing that reflected individuality and joy. While the rationing of food, fabric and everyday essentials continued into the 1950s, this new look offered an exhausted Europe the sense that life would begin once more.

| If magazine |

| Docklands Studios Melbourne is proud to be Australia’s first major film studio powered entirely by renewable electricity. We’ve made the switch to leading government–accredited GreenPower to support the global screen industry’s push to reduce its environmental impact. All our six sounds stages, production offices, mess halls, workshops and administration buildings are now powered by 100% renewable electricity sources such as solar, wind, hydro and biofuel. To discuss stage hire contact us on info@dsmelbourne.com or +61 3 8327 2000 Visit our website https://www.dsmelbourne.com/ |

Good News!!

Why forgetting is a normal function of memory – and when to worry

Published: February 15, 2024 2.20am AEDT and republished under Creative Commons Licence.

Author Alexander Easton Professor of Psychology, Durham University

Disclosure statement – Alexander Easton does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Forgetting in our day to day lives may feel annoying or, as we get older, a little frightening. But it is an entirely normal part of memory – enabling us to move on or make space for new information.

In fact, our memories aren’t as reliable as we may think. But what level of forgetting is actually normal? Is it OK to mix up the names of countries, as US president Joe Biden recently did? Let’s take a look at the evidence.

When we remember something, our brains need to learn it (encode), keep it safe (store) and recover it when needed (retrieve). Forgetting can occur at any point in this process.

When sensory information first comes in to the brain we can’t process it all. We instead use our attention to filter the information so that what’s important can be identified and processed. That process means that when we are encoding our experiences we are mostly encoding the things we are paying attention to.

If someone introduces themselves at a dinner party at the same time as we’re paying attention to something else, we never encode their name. It’s a failure of memory (forgetting), but it’s entirely normal and very common.

Habits and structure, such as always putting our keys in the same place so we don’t have to encode their location, can help us get around this problem.

Rehearsal is also important for memory. If we don’t use it, we lose it. Memories that last the longest are the ones we’ve rehearsed and retold many times (although we often adapt the memory with every retelling, and likely remember the last rehearsal rather than the actual event itself).

In the 1880s, German psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus taught people nonsense syllables they had never heard before, and looked at how much they remembered over time. He showed that, without rehearsal, most of our memory fades within a day or two.

However, if people rehearsed the syllables by having them repeated at regular intervals, this drastically increased the number of syllables that could be remembered for more than just a day.

This need for rehearsal can be another cause of every day forgetting, however. When we go to the supermarket we might encode where we park the car, but when we enter the shop we are busy rehearsing other things we need to remember (our shopping list). As a result, we may forget the location of the car.

However, this shows us another feature of forgetting. We can forget specific information, but remember the gist.

When we walk out of the shop and realise that we don’t remember where we parked the car, we can probably remember whether it was to the left or right of the shop door, on the edge of the car park or towards the centre though. So rather than having to walk round the entire car park to find it, we can search a relatively defined area.

The impact of ageing

As people get older, they worry about their memory more. It’s true that our forgetting becomes more pronounced, but that doesn’t always mean there’s a problem.

The longer we live, the more experiences we have, and the more we have to remember. Not only that, but the experiences have much in common, meaning it can become tricky to separate these events in our memory.

If you’ve only ever experienced a holiday on a beach in Spain once you will remember it with great clarity. However, if you’ve been on many holidays to Spain, in different cities at different times, then remembering whether something happened in the first holiday you took to Barcelona or the second, or whether your brother came with you on the holiday to Majorca or Ibiza, becomes more challenging.

Overlap between memories, or interference, gets in the way of retrieving information. Imagine filing documents on your computer. As you start the process, you have a clear filing system where you can easily place each document so you know where to find it.

But as more and more documents come in, it gets hard to decide which of the folders it belongs to. You may also start putting lots of documents in one folder because they all relate to that item.

This means that, over time, it becomes hard to retrieve the right document when you need it either because you can’t work out where you put it, or because you know where it should be but there are lots of other things there to search through.

It can be disruptive to not forget. Post traumatic stress disorder is an example of a situation in which people can not forget. The memory is persistent, doesn’t fade and often interrupts daily life.

There can be similar experiences with persistent memories in grief or depression, conditions which can make it harder to forget negative information. Here, forgetting would be extremely useful.

Forgetting doesn’t always impair decision making

So forgetting things is common, and as we get older it becomes more common. But forgetting names or dates, as Biden has, doesn’t necessarily impair decision making. Older people can have deep knowledge and good intuition, which can help counteract such memory lapses.

Of course, at times forgetting can be a sign of a bigger problem and might suggest you need to speak to the doctor. Asking the same questions over and over again is a sign that forgetting is more than just a problem of being distracted when you tried to encode it.

Similarly, forgetting your way round very familiar areas is another sign that you are struggling to use cues in the environment to remind you of how to get around. And while forgetting the name of someone at dinner is normal, forgetting how to use your fork and knife isn’t.

Ultimately, forgetting isn’t something to fear – in ourselves or others. It is usually extreme when it’s a sign things are going wrong.

Inside Story

Adventures in feminism

Books | We know a lot about Germaine Greer, but not so much about another trailblazer, Merle Thornton

ZORA SIMIC 20 MAY

Not too much, not too little: Merle Thornton back at the Regatta Hotel in 2015. Michelle Smith/Fairfax

Bringing the Fight: A Firebrand Feminist’s Life of Defiance and Determination

By Merle Thornton, with Melanie Ostell | HarperCollins | $29.99 | 288 pages

Merle Thornton, a true icon of Australian feminism, has published her memoir at the age of ninety and what a delight it is. The pleasure starts with the cover — it’s bright yellow with the title, Bringing the Fight, in bold pink. Right in the middle is a captivating photograph of a youthful, beaming Merle, striding purposefully, dressed in a fetching ensemble with a sturdy bag in her hand and sensibly stylish buckled shoes on her feet.

The photo is dated “c. 1950,” when she was twenty-year-old Merle Wilson and a student at the University of Sydney, a period she describes as “the happiest time of my life.” It was there that she met her future husband, a bookish returned soldier named Neil Thornton; together, they would raise a family and have many adventures. Around 1950, the adventures included discovering sex, being in thrall to the philosopher John Anderson and mixing with the Libertarians who eventually morphed into the Sydney Push, the bohemian scene that incubated Germaine Greer, Clive James, Robert Hughes and other notables.

The Sydney Push would become notorious for its sexism, but by then Merle had moved on to the public service, where she quickly developed strategies to combat boredom and land the better gigs. “Before Germaine, there was Merle,” declares the cover blurb, and indeed there was. We’re very fortunate that Germaine Greer and Merle Thornton are both still with us, but while we know a lot about Greer — too much, perhaps — how much do even the most dedicated students of Australian feminism know about Thornton, other than the 1965 Regatta Hotel protest she is best known for, and perhaps the fact that she’s the mother of actor Sigrid Thornton? Until now, not nearly enough.

What Merle Thornton tells us about her life and times is, on any measure, the right amount — not too much, not too little, coy in parts but candid elsewhere, and vivid throughout. It’s a fast, breezy read, written with the assistance of Melanie Ostell, and grew out of a stage show, Frank and Fearless, commissioned by the Queensland Music Festival, in which Thornton shared stories with her daughter.

It’s a memoir that also wants to inspire and instruct, with life lessons and maxims peppered throughout. The narrative is chronological, peaking in the 1970s, with occasional pauses to showcase “indelible moments” and “bookish influences.” These features sometimes tip over into whimsy, but the overall effect is endearing. As a narrator, Thornton is consistently good company. Crucially, she knows she is a historically significant figure but doesn’t over-inflate her importance. And even without the better-known parts, the nine-decade span of her life makes for fascinating social history.

Thornton was born during the Great Depression and attended Fort Street Girl’s High in Sydney in the 1940s, at a time when the majority of her classmates left school at fifteen. In one memorable observation, she contrasts the femininities of university-bound young women like herself (“dowdy matrons in our black cotton stockings”) and the contemporaries who left school to enter the world of work and romance “dressed in fashionable pencil skirts” with “proper hairdos,” who were like “colourful birds.” “It’s an interesting paradox,” she notes, “that we would learn many different things that these women would never know about, and yet we remained children for so much longer.”

By contemporary standards, Thornton’s life path might be the more common one — she graduated from university, got married, had children and continued to work, study and travel — but some of the most fascinating sections of the book evoke how different Australia was in the 1950s and 1960s, especially for women.

As a university student, she was an anomaly; as a public servant she had to hide her marriage (and for as long as she was able, her first pregnancy) in order to keep her job. In the first decade of her marriage she used a cap and spermicide for contraception, and she recalls that “preparing for sex could be a slow, at times embarrassing and potentially shaming learning experience subject to trial and error.” The arrival of the contraceptive pill in the early 1960s is duly recognised for the seismic event that it was, even if the initial batch gave her migraines.

The 1960s became her decade. At the University of Queensland, where her husband took up a lecturing post in 1960, Thornton threw herself into campus life. In her first direct action, she stormed down the corridor from the dull women’s staffroom to the male common room and sat down, “heart thumping.” Never a fan of single-sex organisations or segregated socialising, she wanted the right to be where the conversation was, regardless of her sex.

In this spirit, Thornton and her friend Rosalie Bogner staged her next direct action, this time on a much more ambitious scale. They chained themselves to the front bar of the Regatta Hotel on 31 March 1965 to protest against liquor laws that excluded women from drinking there. With the press tipped off, their novel action made headlines around the world and inspired a wave of similar protests. For all of its spectacular qualities, however, it’s the quotidian details of the protest that stand out, including the large kilt pin she used to cinch the waist of her skirt, and the performance of deep conversation with Bogner as the action played out. “I have no recollection of what we said to each other,” Thornton recalls, “and wouldn’t be surprised if it was ‘rhubarb, rhubarb, rhubarb.’”

After the Regatta protest, which comes around three-quarters of the way through, the memoir’s energy dissipates somewhat. Riding on the protest’s momentum, Thornton became a “go-to person on the issue of equal rights” and established the Equal Opportunities for Women Association, which successfully lobbied for the removal of the “marriage bar” from the Public Service Act in 1966.

But while Thornton has remained a dedicated feminist, including as a foundational figure in women’s studies at the University of Queensland, women’s liberation was never quite to her taste. Hers is a politics of like-minded people working together for a common cause, whether it’s libertarianism and free thought, Aboriginal rights or equal opportunities for men and women. If at times these principles strike the reader as old-fashioned, this book also provides plenty of reminders — including the groovy cover — that Merle Thornton was a genuine trailblazer. •

Zora Simic is a Senior Lecturer in History and Gender Studies in the School of Humanities and Languages at the University of New South Wales.

Topics: biography | books | history | women

Cindy Lou at coffee in South Canberra

I have been frequenting coffee shops in Deakin, Garran and Hughes as a change from my North Canberra haunts.

Garran Bakery

The photos are from the Garran Bakery site. I visited and had one of their excellent coffees while sitting under the trees. This is a dog friendly cafe with indoor and outdoor seating. The pastries look wonderful, and well worth another visit. Even more important, the staff are friendly and marvelously efficient.

Deakin & Me is a friendly cafe, with indoor and outdoor seating. The coffee is excellent, the pastries very tempting, while the luxurious fruit salad cups add another dimension, as do the generous cooked meals.

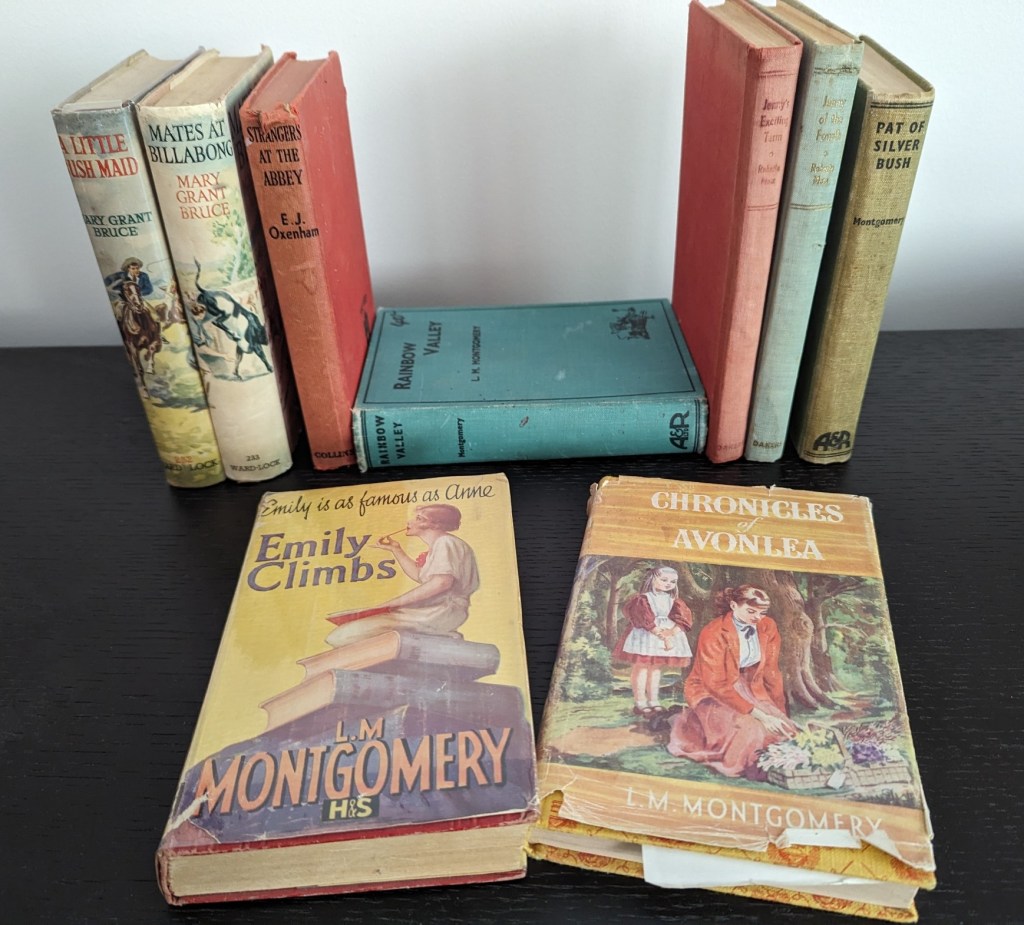

Research Project

Did anyone read these books: the Billabong series by Mary Grant Bruce; L.M. Montgomery’s series, such as Anne of Green Gables, Emily of New Moon, Pat of Silver Bush or standalone novels such as Jane of Lantern Hill; the Abbey books by Elsie J. Oxenham; or Roberta Moss’s Jenny books? I am interested in whether other people can remember reading them in the 1950s and 1960s or can remember them being in their school library.

If so, could you comment in the comments section? Or use messenger if we are connected?

Gen Kitchen, left, won the by-election for Labour in Wellingborough while Damien Egan overturned the Conservative majority in Kingswood © FT Montage/Getty/Reuters

See also Bob McMullan’s article in the blog Week beginning 14 February 2024, (also published in Pearls and Irritations) UK election prospects 2024.