Kerry Wilkinson The Call Bookouture, April 2024.

Thank you, NetGalley, for providing me with this uncorrected proof for review.

I have been an avid follower of Kerry Wilkinson’s work, the stand-alone novels and the absorbing Whitecliff Bay series. The Call, however, has been a great disappointment. Admittedly, I was intrigued by the premise and the first part of the novel. It begins with a scene between two sisters in a beautiful location. Their father’s walking off his back pain from the flight is his familiar reaction to any health issue. Familiar holiday activities on the lake break the silence. Even as the loneliness and difficulty in getting to the holiday house by the lake on Vancouver Island establishes the gradual fear that will grow as the narrative proceeds, a comfortable atmosphere has been established. With a child fast asleep after the flight from England, one husband in bed using his laptop and two sisters reminiscing and drinking happily together, what can go wrong? See Books: Reviews for the complete review.

.

Kerry Fisher Escape to the Rome Apartment Book 3 of The Italian Escape, Bookouture, April 2024.

Thank you, NetGalley, for providing me with this uncorrected proof for review.

Kerry Fisher’s Italian Escape series is a pleasant combination of romance, social commentary and the most engaging descriptions of Italian towns, culture and life. With its two main characters, Ronnie and Marina, friends in their seventies who live in the apartments, some continuing secondary characters and the introduction of new ones, the Italian Escape series is an engaging read. Although I found Books 1 and 2 more absorbing, Book 3 has a charm of its own, beginning with Sara’s escape from her life in England with a demanding husband and twin sons to a chance meeting on the plane with a woman whose joyous approach to life begins to work a change in Sara’s.

Sara, now in her fifties, is returning to Italy years after her romance with an Italian lover failed. Although this provides a background to her visit, most importantly she has returned to scatter the ashes of her best friend, Lainie, with whom she spent a summer in Italy. She has spent her life after this joyous time bowing to society’s expectations. However, even before she reaches the Rome apartment where Ronnie and Marina’s plans help women change their expectations of what life can offer them, Sara has rebelled. She has refused to bend to her tyrannical boss at the prestigious women’s magazine where she is lifestyle editor, giving her the opportunity to stay in Italy for as long as she wants. It will take her longer to change her wife and mothering mode, but this at least is a start. See Books: Reviews for the complete review.

The Saturday Read: Bright green light

Harry Lambert @harrytlambert1 link

Staff writer, New Statesman | Editor, The Saturday Read https://saturdayread.substack.com/

Remnants of a Legendary Typeface Have Been Rescued From the River Thames

Doves Type was thrown into the water a century ago, following a dispute between its creators.

by Holly Black May 5, 2024

The depths of the river Thames in London hold many unexpected stories, gleaned from the recovery of prehistoric tools, Roman pottery, medieval jewelry, and much more besides. Yet the tale of the lost (and since recovered) Doves typeface is surely one of the most peculiar.

A little over a century ago, the printer T.J. Cobden-Sanderson took it upon himself to surreptitiously dump every piece of this carefully honed metal letterpress type into the river. It was an act of retribution against his business partner, Emery Walker, whom he believed was attempting to swindle him.

The pair had conceived this idiosyncratic Arts and Crafts typeface when they founded the Doves Press in the London’s Hammersmith neighborhood, in 1900. They worked with draftsman Percy Tiffin and master punch-cutter Edward Prince to faithfully recall the Renaissance clarity of 15th-century Venetian fonts, designed by the revolutionary master typographer Nicolas Jensen.

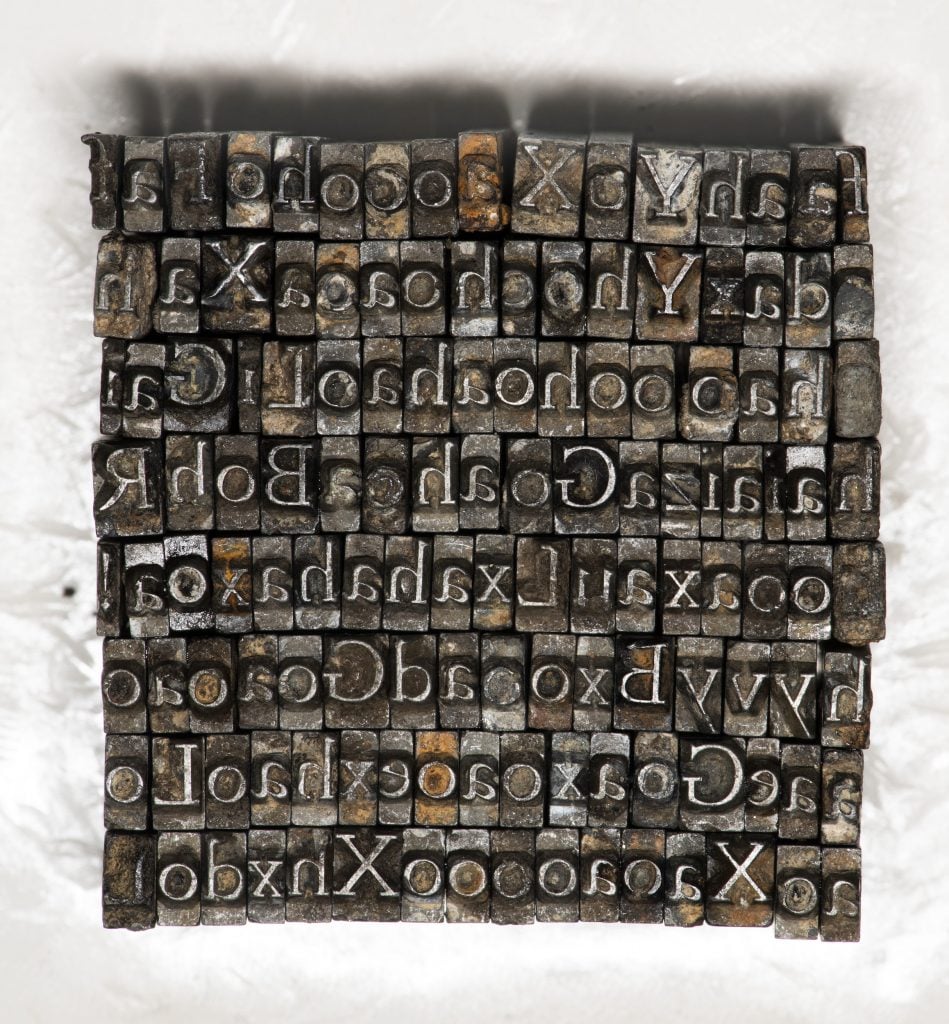

Doves Type recovered by Robert Green, 2014. Photo Matthew Williams Ellis

With its extra-wide capital letters, diamond shaped punctuation and unique off-kilter dots on the letter “i,” Doves Type became the press’s hallmark, surpassing fussier typographic attempts by their friend and sometime collaborator, William Morris.

The letterforms only existed as a unique 16pt edition, meaning that when Cobden-Sanderson decided to “bequeath” every single piece of molded lead to the Thames, he effectively destroyed any prospect of the typeface ever being printed again. That might well have been the case, were it not for several individuals and a particularly tenacious graphic designer.

Robert Green first became fascinated with Doves Type in the mid-2000s, scouring printed editions and online facsimiles, to try and faithfully redraw and digitize every line. In 2013, he released the first downloadable version on typespec, but remained dissatisfied. In October 2014, he decided to take to the river to see if he could find any of the original pieces.

Doves Type recovered and held here by Lukasz Orlinski at Emery Walker’s House. Photo: Lucinda MacPherson.

Using historical accounts and Cobden-Sanderson’s diaries, he pinpointed the exact spot where the printer had offloaded his wares, from a shadowy spot on Hammersmith bridge. “I’d only been down there 20 minutes and I found three pieces,” he said. “So, I got in touch with the Port of London Authority and they came down to search in a meticulous spiral.” The team of scuba divers used the rather low-tech tools of a bucket and a sieve to sift through the riverbed.

Green managed to recover a total of 151 sorts (the name for individual pieces of type) out of a possible 500,000. “It’s a tiny fraction, but when I was down by the river on my own, for one second it all felt very cosmic,” he said. “It was like Cobden-Sanderson had dropped the type from the bridge and straight into my hands. Time just collapsed.”

The finds have enabled him to further develop his digitized version and has also connected him with official mudlarks (people who search riverbanks for lost treasures, with special permits issued) who have uncovered even more of the type.

A mudlark by the Thames with Hammersmith Bridge in background. Photo: Lucinda MacPherson.

Jason Sandy, an architect, author and member of the Society of Thames Mudlarks, found 12 pieces, which he has donated to Emery Walker’s House at 7 Hammersmith Terrace. This private museum was once home to both business partners, and retains its stunning domestic Arts and Crafts interior.

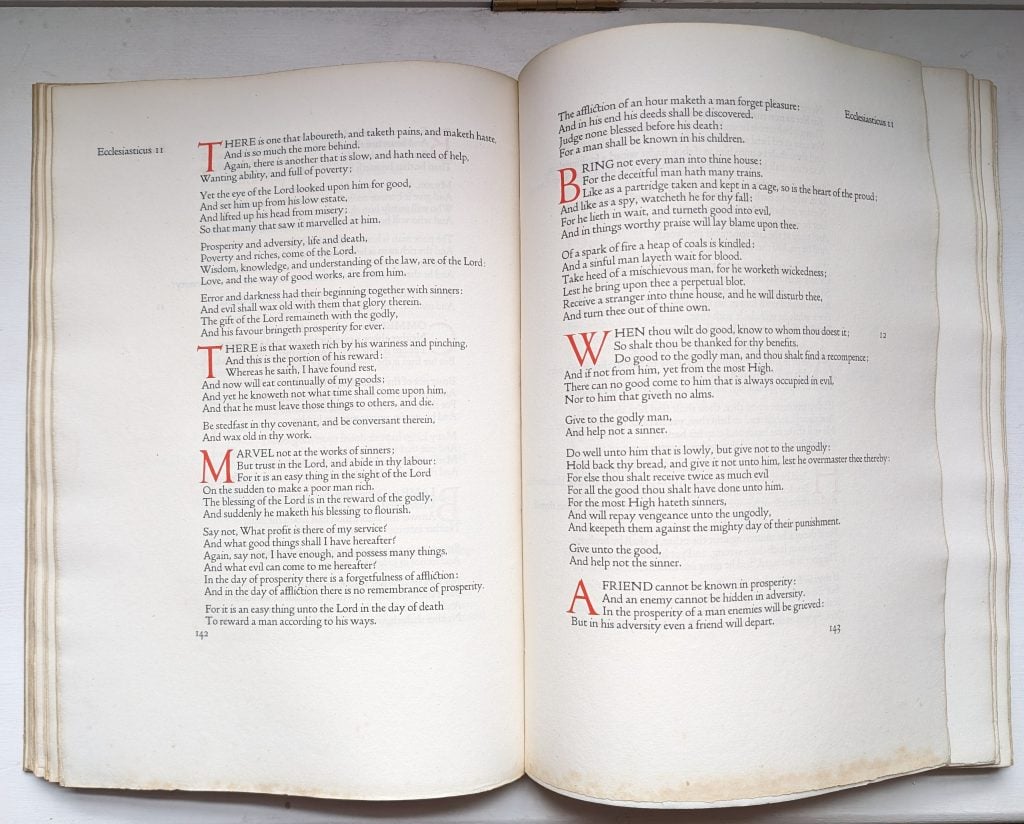

Much like Green, Sandy was captivated by the Doves Type story, and mounted an exhibition at the house that displays hundreds of these salvaged pieces, including those discovered by Green, as well as mudlarks Lucasz Orlinski and Angus McArthur. The show was supplemented by a whole host of Sandy’s other finds, including jewelry and tools. An extant copy of the Doves English Bible is also on display.

The Doves Bible returns to Emery Walker’s House. Photo: Lucinda MacPherson.

“It is not that unusual to find pieces of type in the river,” Sandy said. “Particularly around Fleet Street, where newspaper typesetters would throw pieces in the water when they couldn’t be bothered to put them back in their cases. But this is a legendary story and we mudlarks love a good challenge.” The community is naturally secretive about exactly where and how things are found. For example, Orlinski has worked under the cover of night with a head torch, to search for treasures at his own mysterious spot on the riverbank.

For Sandy, the thrill comes from the discovery of both rare and everyday artifacts, which can lead to an entirely new line of inquiry: “The Thames is very democratic. It gives you a clear picture of what people have been wearing or using over thousands of years. And it’s not carefully curated by a museum. The river gives up these objects randomly, and you experience these amazing stories of ordinary Londoners. It creates a very tangible connection to the past. Every object leads you down a rabbit hole.”

“Mudlarking: Unearthing London’s Past” is at Emery Walker’s House, 7 Hammersmith Terrace, London, through May 30.

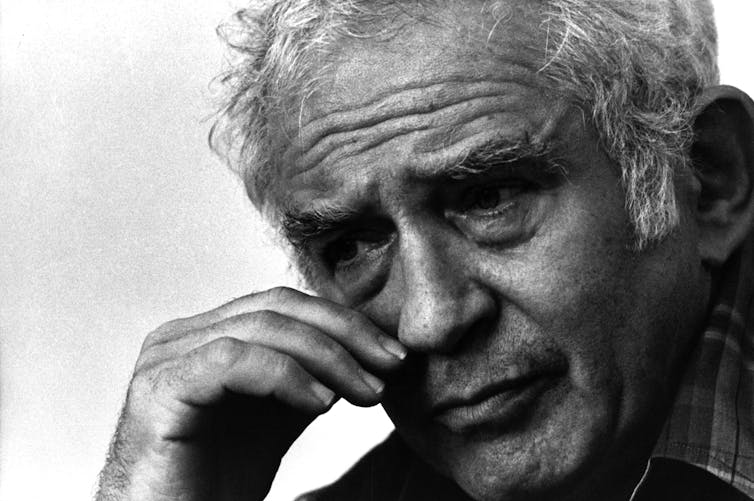

Kate Millett pioneered the term ‘sexual politics’ and explained the links between sex and power. Her book changed my life

Published: May 3, 2024 6.11am AEST

Barbara Caine

Professor of History

2011–2019 Professor of History and Head of the School of Philosophical and Historical Studies, University of Sydney

I am a historian interested in histories of feminism and in questions about history and the individual life. My publications include: Biography and History, Forthcoming April 2010, Palgrave Macmillan (History and Theory series)

“Destined to be Wives: The Sisters of Beatrice Webb”, Oxford University Press, 1986, “Victorian Feminists”, Oxford University Press, 1992,” English Feminism, c1780-1970, Oxford University Press”, 1997, Bombay to Bloomsbury: the Stracheys, c 1850-1950, Oxford University Press, 2005, Biography and History, Bloomsbury 2012, Women and the Autobiographical Impulse, Bloomsbury 2023. I was one of the editors of the Companion to Australian Feminism, Oxford 1998.

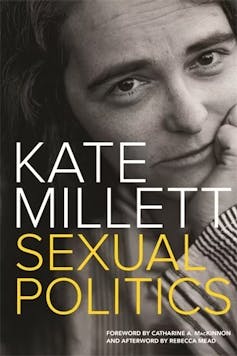

I still think of Kate Millett’s Sexual Politics as the book that changed my life. Its insistence on the importance of patriarchal structures and sexual hierarchies in literature and history, as well as in contemporary society, was eye-opening.

The 1970s saw the publication of several classic feminist texts, including Shulamith Firestone’s The Dialectic of Sex, Eva Figes’ Patriarchal Attitudes and Germaine Greer’s The Female Eunuch. For the most part, these books grew out of the discussions and consciousness-raising groups associated with the early stages of the Women’s Liberation movement.

Many women who became feminists in the 1970s still ask which of these books was most important to them. For me, the answer is unquestionably Sexual Politics.

I was a graduate student, just embarking on a PhD on a Victorian man of letters, when I first read Sexual Politics (or rather, a review of it that sent me racing for the book). It offered a whole new approach to history and to intellectual life.

Until I read it, I lacked the self-confidence – and even the language required – to address the history of the 19th century from the vantage point of a woman. I had believed in the notions of scholarly impartiality and “objectivity” that were dominant in the 1960s – and would come to be seen as expressing views reflecting the position of privileged white men.

Armed with a new critical stance, I went on to become a feminist historian, teaching and researching women’s lives and the history of feminism.

The term “sexual politics”, very widely used now, was then quite new. Millett was the first person to use it in print. Aware it was not only new, but controversial (and to some, incomprehensible), she explained at some length why she saw sexual relationships – and indeed the act of sex itself – as political.

She explained why we needed to move beyond using the term “political” just to refer to a narrow world of parties, chairmen and meetings. Its use, she argued, should be extended to describe “power-structured relationships, to all arrangements whereby one group of persons is controlled by another”.

Power, sex, Miller and Mailer

To emphasise the power structure in sexual relationships, Millet began the book with an extended passage from Henry Miller’s Sexus, which graphically depicts a cruel sexual conquest. It reads in part:

It happened so quickly that she didn’t have time to rebel or even to pretend to rebel. In a moment I had her in the tub, stockings and all […] I lay back and pulled her on top of me. She was just like a bitch in heat, biting me all over, panting, gasping, wriggling like a worm on the hook.

The brutal misogyny evident in Miller’s laudatory depiction of the way his hero, Val, sexually dominates and subdues Ida, the wife of his erstwhile friend, Bill Woodruff, is as shocking to read now as it was in 1970.

Back then, Millett’s insistence on discussing the misogyny in this widely admired text was striking. So was her refusal to privilege the book’s freedom and sexual explicitness as the topic of discussion. The “almost supernatural sense of power” and dominance a male reader might experience, she argued, was very different from what a female reader might experience.

In a chapter titled “Instances of Sexual Politics”, Millett turned from Miller to another iconic mid-20th-century male novelist, Norman Mailer, and his book, An American Dream. Her discussion underlined the extreme violence towards women the kind of sexual domination in Miller and Mailer’s work could encompass. (Ironically, perhaps, the current cover of the Modern Classics edition of Sexus carries a rave from Mailer.)

On hearing the wife he had separated from had engaged in sex with others (something he had done even during their marriage), Rojack, Mailer’s hero, first sodomises and then kills her. Both Rojack and his creator seem to feel this act is entirely justified. There is little motive for this killing, Millett notes, “beyond the fact that he is unable to master her in any other way”. Rojack is exhausted when he finishes – though he now feels triumphant and follows this act of mastery by buggering her maid.

At a time when there is so much awareness of the link between gender hierarchies and disrespect for women with rape and domestic violence, it is quite shocking to see how recent our consciousness of these connections are.

Both Miller and Mailer, as Millett shows, depict their violent, controlling men as heroes. They are entitled to project their masculinity and demand its recognition in ways that would be unthinkable in ostensibly serious literature now.

Her feminist critique of these immensely influential male novelists was unprecedented. The fact she began and ended her book with this critique illustrates how seriously she took literature and ideas. She saw them as the basis of political consciousness and conduct.

But not all literary depictions of sexual cruelty take this triumphalist tone, Millett argues. She cites the example of French writer Jean Genet, who was abandoned by his mother, spent part of his adolescence at a reform school and spent time as a homeless male prostitute. Drawing on his own painful personal experiences, Millett argues, Genet depicts sexual violence and brutality from the vantage point of those subjected to it.

Operating in a homosexual world, he sometimes chooses drag queen prostitutes brutalised by pimps, clients and lovers for this purpose. The abject drag queens at the bottom of this hierarchy show what it is to be female, in this “mirror society of heterosexuality”. Genet also wrote about women, in his play The Maids and other works, using them, too, to show that brutal sexual hierarchies both reflect and provide the foundations for other social hierarchies and structures.

For Genet, Millet argues approvingly, sex and the power structure around it is “the most pernicious of the systems of oppression”.

Naming and defining ‘patriarchy’

As she moved from discussing “instances of sexual politics” to articulating its theory, Millett, like many other feminists of the 1970s, framed her discussion in terms of the patriarchy. The naming and defining of “patriarchy” as a system “whereby that half of the populace which is female is controlled by that half which is male”, was seen at the time as a major step in understanding the nature of women’s oppression.

It offered a framework for showing how widespread the oppression of women was – and the many ways it was reinforced. It was not only a system of government, but an ideology that conditioned both men and women to accept a particular form of sexual hierarchy and to develop an appropriate understanding of their role, status and temperament within it.

The concept of patriarchy also offered a way of understanding the consequences of the biological differences between the sexes. It could be seen in sociological terms in the constitution of the family. There was an anthropological dimension, too, as it was reinforced through myth and religion.

Psychologically, it was reinforced through the infantilisation of women and in their internalised sense of inferiority and self-hatred. Patriarchy could also be seen in economic and educational systems that perpetuate women’s inferiority and economic dependence – and in the many ways force has been used in legal and cultural systems.

Intellectual courage and imaginative power

Millett’s discussion of sexual politics was extraordinarily wide-ranging. After introducing some of her key literary texts, she provided an extended historical discussion of the 19th and early 20th centuries, as historical background to the present.

Broadly linking Britain and America, she explored what she saw as the “first sexual revolution”: the 19th-century feminist campaigns for women’s education and political rights, and the texts, like John Stuart Mill’s essay The Subjection of Women, that delineated and critiqued the inferior position occupied by women.

In Millett’s historical sweep, the 19th-century sexual revolution was followed by a counterrevolution, comprising the attacks on women’s rights evident in Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union under Stalin, on one hand, and the impact on American women of Freudian psychoanalysis and the ideas of some of the post-Freudians, on the other.

The concept of “penis envy” was a particular target, showing so clearly how women’s inferiority was internalised. The counterrevolution provides the context for the more detailed discussion of the male novelists who are dealt with in more detail in the book’s final section – where D.H. Lawrence is added to Miller and Mailer. These three iconic male writers, who both reflect and shape cultural attitudes, are described by Millett as “counter-revolutionary sexual politicians”.

The scope of Millett’s discussion is impressive. Its breadth speaks both to her own intellectual courage and imaginative power, and to the limited state of scholarship on women at the time she was writing.

This book began as a PhD at Columbia University. While Millett was allowed extraordinary latitude, she had to make do with very limited resources. If one were attempting to cover the historical span she dealt with now, one would be overwhelmed by the vast scholarship on gender in the history, literature and sociology of the 19th and 20th centuries that she addresses. But all of this was in the future, and she had to make do with a very small number of works, as her own bibliography makes clear.

‘A revelation’ or ‘like homework’?

It was the combination of this broad scope and her incredible intellectual freedom and independence that were most important to me when I first read her book.

Millett was a revelation, with her sharp (and sometimes funny) feminist critique of canonical texts and her critical reading of history that placed women at the centre. I was also struck by her endorsement of some historical figures, like John Stuart Mill, and ridiculing of others, like art critic John Ruskin or Tennyson.

Her analysis of the Victorian period was particularly appealing to me, but so too was her literary analysis. All these things would become central in feminist scholarship in the subsequent decades. But her work linked this scholarly dimension to a contemporary political critique and program.

For Millett, this critical reading of these canonical male texts was in itself a political act, demolishing a canon and allowing a new space for women to read. I found it exhilarating – though it did mean I ultimately abandoned that PhD.

Some found Sexual Politics hard to read and too abstract to be of use to contemporaries concerned about women. In the Guardian, Emily Wilson suggested it could feel “at times, just a wee bit like homework”. But its energy and sweep appealed to many – and Wilson herself concluded “you will undoubtedly be a better woman for it”. Sexual Politics was a sensation, an instant bestseller, and for a couple of years Millett found herself constantly giving university talks and lectures, and appearing in the media.

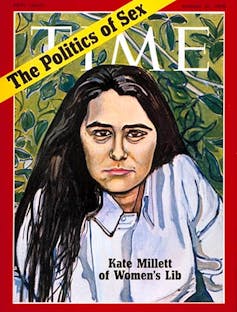

She was seen by some as the central intellectual figure in the women’s movement – not a status she ever sought or claimed. Shortly after the book was published, she featured on the cover of Time Magazine in August 1970, an extended and rather curious essay titled: “Who’s come a long way, baby?”.

The essay is curious because the author seems to have not quite decided whether to praise Millett or condemn her. Sexual Politics had then sold more than 15,000 copies and was in its fourth edition – despite being, as the essay noted, “a polemic suspended awkwardly in academic traction”. Alongside its presentation of Millett’s views, the essay offered facts and figures to confirm the subordinate status of women in the United States and an account of the lengthy battle waged for women’s rights.

At times, it seemed almost admiring – and to seek to support her overall argument. But it made the discomfort of some of her male readers very clear, quoting one of her thesis examiners, who said reading the book “is like sitting with your testicles in a nutcracker”. The sting was there from the start, however. Millett was described not only as an “ideologue”, but as “the Mao Tse-tung of Women’s Liberation” – which didn’t reflect her sense of intellectual freedom.

The essay also quoted several male anthropologists and medical specialists who questioned her scholarship in their particular area and deplored her lack of concern about motherhood. Some, like Canadian anthropologist Lionel Tiger, then became the subject of feminist criticism. But in the essay, their expertise is unquestioned.

Whatever admiration there was disappeared six months later, when Time published another article: Women’s Lib: a Second Look. This piece consisted entirely of criticisms of Millett’s views and “lack of intellectual sophistication”: from Irving Howe, Tiger (again), and some women, including Janet Malcolm.

In the earlier article, questions about lesbianism as a source of division within the women’s movement had been raised. Here, to seal Time’s disapproval – and make sure she was no longer acceptable – the magazine outed her as “bisexual”. The discomfort Millett caused male readers became evident in other publications too, especially from literary men. She was subjected to a vicious critique from Irving Howe in Harper’s Magazine and became the central target of Norman Mailer’s extraordinary satirical outpouring of male woe, The Prisoner of Sex.

A forgotten feminist?

Millett’s initial popularity did not endure. She faced hostility from within the women’s movement, too. Some demanded a closer identification with lesbian women, both publicly and in print. Others felt no one should be allowed to occupy the position of intellectual leader in a movement so hostile to hierarchy and structure.

Much has been made of the fact that, by the mid-1990s, Sexual Politics was no longer in print. At this time, Millett was describing herself as “the feminist time forgot”. Sexual Politics continued to be read, however, and extracted for collections and anthologies.

The question of Millett’s continuing influence is a complex one and its form sometimes amorphous. Although it is academics who write most often about her, she did not – and indeed did not intend to – set a research agenda. Some of her ideas and approaches were directly challenged by the new feminist scholarship across the humanities and social sciences that developed in the 1970s and ‘80s. Her antipathy to Freud, for example, was rejected by feminists who saw psychoanalysis as offering important insights into femininity and how women understood and experienced it.

The concept of patriarchy, too, was being questioned by feminist scholars like Veronica Beechey and Joan Acker, who felt this notion of a global and almost universal system of male domination was unhelpful. It lacked specificity. On one hand, it made it hard to analyse the different kinds of sexual hierarchies that existed in different times and places. On the other, it seemed to deny women any kind of agency in negotiating the structures they lived under, or in determining their own lives.

For many of those involved in feminist scholarship from the 1970s onwards, it was studying women’s lives and activities, their contribution to literature, history and society that seemed important – rather than focusing only on their oppression.

Quite apart from these specific issues, however, There is a very strong sense among many academics, journalists and feminist activists of the later 20th century that Millett who opened their eyes to the sexist world around them. “The world was sleeping,” Andrea Dworkin wrote, “and Millett woke it up.”

Sexual Politics may have been out of print in the 1990s, but it reappeared in 2000. And it was republished again, to much more acclaim, in 2016, with a foreword by noted feminist Catharine A. MacKinnon and an afterword by New Yorker writer Rebecca Mead. This time, it received serious attention from some of the mainstream liberal press (including The New Yorker and The New Republic) that had ignored it the first time round.

There is a strong sense in these articles that Sexual Politics was a product of its time. That emphasis on the importance of critical reading, its linking of cultural criticism with radical politics and its optimism about the possibility of a sexual revolution that would bring about a complete reordering of the sexual hierarchy all belong to the 1970s.

Millett’s death in 2017 led to more discussion of her importance to a whole generation of feminists. Her sense of the importance of ideas and her optimism now seem utopian. But for many of us who read Millett in the 1970s, these very qualities helped give us the courage to challenge the intellectual and political worlds we lived in. For some of us, it changed our lives.

Kate Millett as a source in Chapter 6, “Seventies Success”, The Reality behind Barbara Pym’s Excellent Women The Troublesome Woman Revealed, Robin R. Joyce, Cambridge Scholars publishing 2023.

The cultural atmosphere of the 1970s was also more hospitable to the bolder language which was adopted by Weldon. Modern feminist debate provided the background to Weldon and Fairbairns’ first, and Pym’s last, novels. While the debate began with Friedan, whose 1960s work provided much of the impetus for the sort of ideas expressed in Pym’s early work, she wrote An Academic Question when a plethora of writers from Britain, America, Australia, and New Zealand began articulating feminist concerns. The 1970s theorists also concerned themselves with marriage, paid work, and economics. These writers included women such as Robin Morgan,[i] Juliet Mitchell,[ii] Germaine Greer,[iii] Kate Millett,[iv] and Sheila Rowbotham.[v] Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex, first published in 1949, was reprinted in 1972. Some men were also interested in feminist topics, for example, Ross Davies published Women and Work[vi]in 1975 and Richard J. Evans[vii] produced a wide-ranging history of women’s movements, The Feminists in 1977.

[i] Robin Morgan, Sisterhood is Powerful (New York: Random House, A vintage Book, 1979).

[ii] Juliet Mitchell, Woman’s Estate (New York: Pantheon, 1971).

[iii] Germaine Greer, The Female Eunuch, (London: Paladin Press,1971).

[iv] Kate Millett, Sexual Politics, (New York: Doubleday, 1979).

[v] Sheila Rowbotham, Women, Resistance and Revolution, 1972, and Hidden from History, 1975.

[vi] Ross Davies, Women and Work (Beverly Hills: Sage Publications, 1975).

[vii] Richard J. Evans, The Feminists: Women’s Emancipation Movements in Europe, America and Australasia 1840-1920 (London: Helm, 1977).

Briefly Noted, from The New Yorker*

“Shakespeare’s Sisters,” [“Limitarianism,” “Rough Trade,” and “Leaving” – not included here.]

May 6, 2024

Shakespeare’s Sisters by Ramie Targoff (Knopf). In this thoughtful study, Targoff, a literary scholar, highlights four female contemporaries of Shakespeare, women who “weren’t encouraged” and rarely received “even a shred of acclaim,” but managed to write nonetheless. Mary Sidney (the sister of the poet Sir Philip Sidney) produced a noteworthy translation of the Book of Psalms. Elizabeth Cary wrote “The Tragedy of Mariam,” the first original play published by a woman in England. Aemilia Lanyer was the first published English female poet of the seventeenth century, thanks to her “Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum,” which mounted a “defense of women’s rights.” Anne Clifford, a voracious reader born to aristocrats, wrote a detailed journal; by “treating herself as a historical subject living an important life,” Targoff argues, she became the “most important female diarist” of her time.

See also, my review of Shakespeare’s Sisters in my blog, January 31, 2024.