Susan Smocer Platt Love, Politics, and Other Scary Things A Memoir Bold Story Press|Independent Book Publishers Association (IBPA), Members’ Titles, December 2024.

Thank you, NetGalley, for providing me with this uncorrected proof for review.

Susan Smocer Platt was unknown to me. However, with Senator Amy Klobuchar’s endorsement of her book I decided it could be well worth reading. Senator Klobuchur was a candidate for the American presidency when eventually the man who was to become president in 2020, Senator Joe Biden, was endorsed. She withdrew with grace, and supported him with warmth, a combination that has remained throughout the Biden/Harris presidency, and since. My feeling that her endorsement provided a good reason to read this book was justified. It begins with gentle and warm stories about the love for each other, and for a political life of decent endeavour, of two American political figures, Susan Smocer Platt, and her husband, Ron Platt.

The first chapter explains, with a colourful title, ‘Fried Okra and Halsuki or Chicken Fried Steak and Hoagies? the differences between the couple, Susan from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania and Ron from Ada, Wyoming. The introduction to the couple is lively, descriptive and while short, not lacking in the detail that makes them into a couple about whom you would like to know more. This follows into Chapter 2, where Washington D.C. is presented as a capital worth knowing and appealing. One which the couple obviously loved, housing an ideal of government that they also clearly endorsed. This positive attitude permeates the book, giving life to the political process, depicting it as worthwhile, its values worth thoughtful consideration and its representatives worth evaluating with care. See Books: Reviews for the complete review.

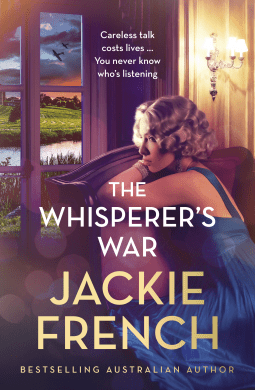

Jackie French The Whisperer’s War Harlequin Australia, HQ (Fiction, Non Fiction, YA) & MIRA, March 2025.

Thank you, NetGalley, for providing me with this uncorrected proof for review.

The Whisperer’s War begins with revelations that, while startling, are demonstrated to be a possible scenario as the supporting material at the end of the book suggests. What is even more important is the underlying philosophy that gives the claims gravitas. Jackie French is writing about more than World War 2 as it was experienced in Britian, and in less detail, in Australia. She bravely puts class, race, the environment, the causes of war and the secrets that are endemic, with cruelty a predominant feature as the foundation to that secrecy, at the forefront of her novel. At the same time, she introduces engaging characters, a storyline that goes beyond the allied victory, and a pleasing, but with complexities intact, resolution.

Lady Deanna of Claverton Castle is a spy, providing information about fascist sympathisers for British intelligence. She is also an inveterate farmer of potatoes, enmeshed in digging manure and doing her best to avoid becoming a recipient of child evacuees. When she cannot evade the three homeless, voiceless sisters who emerge as leftovers after the careful planning and housing of all the other children, Deanna takes them home. Thus, she begins a life coming to terms with the mystery of the girls’ identities and past, the secrecy that she must continue to assume, the mystery around an Australian pilot, Sam, whom they befriend, and the return of her cousin and his clandestine activities. See Books: Reviews for the complete review.

Despite some key milestones since 2000, Australia still has a long way to go on gender equality

Published: March 24, 2025 6.10am AEDT

Janeen Baxter. Director, ARC Life Course Centre and ARC Kathleen Fitzpatrick Laureate Fellow, The University of Queensland

The Conversation, article republished under

Australia has a gender problem. Despite social, economic and political reform aimed at improving opportunities for women, gender gaps are increasing and Australia is falling behind other countries.

The World Economic Forum currently places Australia 24th among 146 countries, down from 15th in 2006. At the current rate of change, the forum suggests it will take more than 130 years to achieve gender equality globally.

Australia has taken important steps forward in some areas, while progress in other areas remains painfully slow. So how far have we come since 2000, and how much further do we have to go?

The good stuff

There are now more women in the labour market, in parliament, and leading large companies than at any other time.

Over the past 25 years, there have been major social and political milestones that indicate progress.

These include the appointment of Australia’s first female governor-general in 2008 and prime minister in 2010, the introduction of universal paid parental leave in 2011, a high-profile inquiry into workplace sexual harassment in 2020, and new legislation requiring the public reporting of gender pay gaps in 2023.

Timeline of equality milestones

- 2000Child Care Benefit introduced, subsidising cost of children for eligible families

- 2008First female Governor-General (Dame Quentin Bryce)

- 2010First female Prime Minister elected (Julia Gillard)

First Aboriginal woman from Australia elected to UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (Megan Davis)

Australia’s first national paid parental leave scheme - 2012Julia Gillard misogyny speech

Workplace Gender Equality Act becomes law, Workplace Gender Equality Agency established - 2013Dad or Partner Pay Leave commenced

- 2016First Indigenous woman elected to House of Representatives (Linda Burney)

- 2017Launch of Women’s Australian Football League

#metoo movement spreads globally to draw attention to sexual harassment and assault - 2020Respect@Work National Inquiry into sexual harassment in the Australian workplace chaired by Kate Jenkins released.

- 2021Grace Tame named Australian of the Year for her advocacy in sexual violence/harassment campaigns

Independent review into Commonwealth parliamentary workplaces launched - 2022National plan to end violence against women is finalised

- 2023Closing the Gender Pay Gap Bill passes parliament

- 2024Superannuation on government-funded paid parental leave from July 1, 2025

Parental leave to be increased to 26 weeks from July 2026.

There are, however, other areas where progress is agonisingly slow.

Violence and financial insecurity

Women are more likely to be in casual and part-time employment than men. This is part of the reason women retire with about half the superannuation savings of men.

This is also linked to financial insecurity later in life. Older women are among the fastest-growing groups of people experiencing homelessness.

The situation for First Nations women is even more severe. The most recent Closing the Gap report indicates First Nations women and children are 33 times more likely to be hospitalised due to violence compared with non-Indigenous women.

They are also seven times more likely to die from family violence.

Improving outcomes for Indigenous women and children requires tackling the long-term effects of colonisation, removal from Country, the Stolen Generations, incarceration and intergenerational trauma. This means challenging not only gender inequality but also racism, discrimination and violence.

At work, the latest data from the Workplace Gender Equality Agency suggests the gender pay gap is narrowing, with 56% of organisations reporting improvements.

On average, though, the pay gap is still substantial at 21.8% with women earning only 78 cents for every $1 earned by men. This totals an average yearly shortfall of $28,425.

There are also some notable organisations where the gender pay gap has widened.

The burden of unpaid work

Another measure of inequality that has proved stubbornly slow to change is women’s unequal responsibilities for unpaid domestic and care work.

Without real change in gender divisions of time spent on unpaid housework and care, our capacity to move towards equality in pay gaps and employment is very limited.

Australian women undertake almost 70% of unpaid household labour. The latest Australian Bureau of Statistics time use data show that of those who participate in domestic labour, women spend an average of 4.13 hours per day on unpaid domestic and care work, compared with men’s 2.14 hours.

This gap equates to more than a third of a full-time job. If we add up all work (domestic, care and paid), mothers have the longest working week by about 10 hours. This has changed very little over time.

These charts, based on analyses of data from the Households, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) study, show what drives this gap.

Women respond to increased demand for care and domestic work by doing more, while men do not. Parenthood significantly increases the time women spend on unpaid care and housework, while also reducing their time in employment.

Men increase their time in unpaid care after a birth, but the jump is minor compared with women, and there is no change to men’s employment hours.

Not surprisingly given these patterns, parenthood is associated with substantial declines in women’s employment hours, earnings, career progression, and mental health and wellbeing.

The way forward

Current policy priorities primarily incentivise women to remain in employment, while continuing to undertake a disproportionate share of unpaid family work, through moving to part-time employment or making use of other forms of workplace flexibility. This approach focuses on “fixing” women rather than on the structural roots of the problem.

There is limited financial or cultural encouragement for men to step out of employment for care work, or reduce their hours, despite the introduction of a two-week Dad and Partner Pay scheme in 2013 and more recent changes to expand support and access.

Fathers who wish to be more actively involved in care and family life face significant financial barriers, with current schemes only covering a basic wage. If one member of the family has to take time out or reduce their hours, it usually makes financial sense for this to be a woman, given the gender earning gap.

The benefits of enabling men to share care work will not only be improvements for women, but will also improve family relationships and outcomes for children.

Research shows relationship conflict declines when men do more at home. Time spent with fathers has been found to be especially beneficial for children’s cognitive development.

Fixing the gender problem is not just about helping women. It’s good for everyone.

Gender inequality costs the Australian economy $225 billion annually, or 12% of gross domestic product.

Globally, the World Bank estimates gender inequality costs US$160.2 trillion. We can’t afford to slip further behind or to take more than a century to fix the problem.

This piece is part of a series on how Australia has changed since the year 2000. You can read other pieces in the series here.

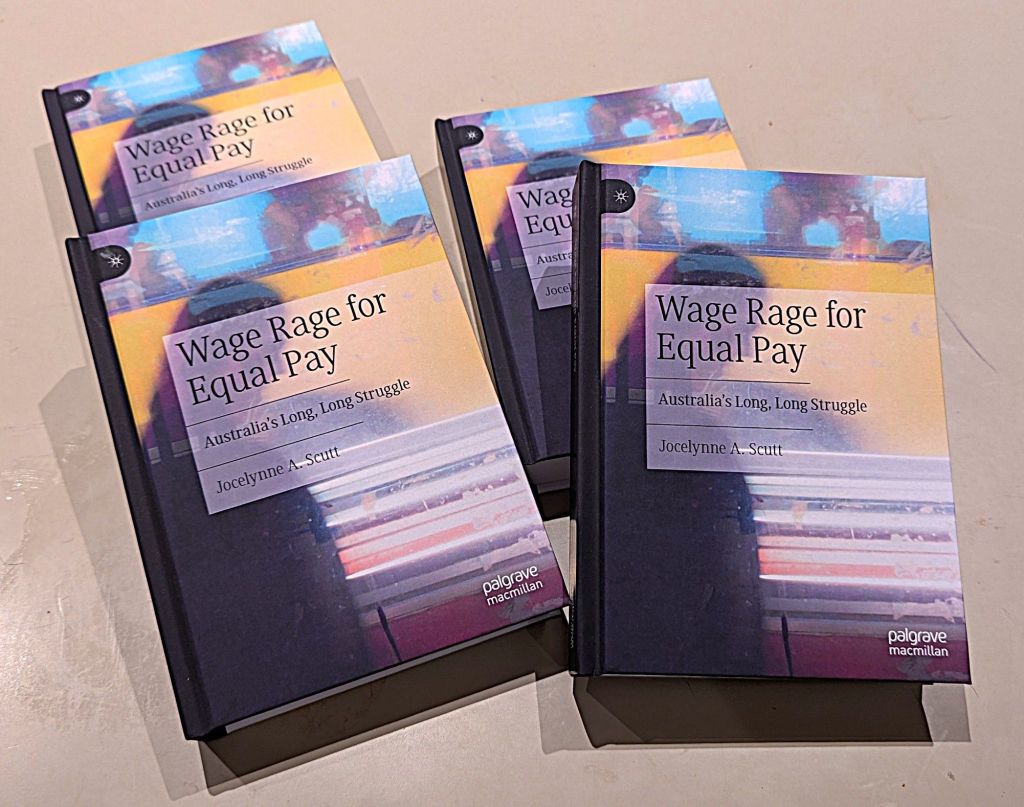

Wage Rage for Equal Pay – new publication from Jocelynne A. Scutt

From the back cover:

This book makes a major contribution to the continuing legal and historical struggle for equal pay in Australia, with international references, including Canada, the UK and the US. It takes law, history and women’s and gender studies to analyses and recount campaigns, cases and debates. Industrial bodies federally and around Australia have grappled with this issue from the late nineteenth to early twentieth century onwards. This book traces the struggle through the decades, looking at women’s organisations activism and demands, union ‘pro’ and ‘against’ activity, and the ‘official’ approach in tribunals, boards and courts.

Chapter 16, Alarums and Excursions: Fictions, Fallacies and Fancies, covers just the type of material I love. Beginning with quotes from Ruth Parks’ Missus and Dorothy Hewitt’s Bobin Up, this chapter is a delightful read – as well as almost a horror story. After all, when Park writes:

Knowing she had no means of support and was desperate for work, the manager offered her less than the single girls, who were receiving only half the male rate anyway. The pittance was enough for food, but not for lodging. Josie set her teeth and accepted it.

And as if this were not enough, Hewitt’s stark comment: There’s a name for men who live off women.

Mary Parker’s ‘oh, such commonplace story’ (p.366) such a graphic and heartrending recall of women’s parlous position as depicted in Come in Spinner introduces yet another of the challenges to women receiving equal pay. Come in Spinner provides much more material, interspersed with non-fiction events such as the National Wage Case 1988, Maternity Leave Cases and Family and Parental and Leave Cases, Equal Opportunity Cases, the Nurses Comparable Worth Case 1985 -1986, Equal Pay Cases 1969 and 1972, the Minimum Wage Case 1974, National Wages Cases 1983 and 1988, books such as The Dialectic of Sex and Exiles at Home and newspaper articles. But, back to the fiction: Ride on Stranger, The Fortunes of Richard Mahoney, My Brilliant Career Goes Bung, Fugitive Anne: A Romance of the Unexplored Bush, Up the Murray, A Marked Man, The Three Miss Kings, Sisters, The Bond of Wedlock, The White Topee, My Brilliant Career – all have their place in Jocelynne Scutt’s Wage Rage for Equal Pay.

This is not an easy read, but this ingenious weaving together of fact and fictionalisation of fact makes an exceptionally interesting chapter.

Australian Politics

More about reality television! Below is an article that demonstrates the way in which some contestants on reality television programs make a valuable contribution to public debate after the reality program is long over. Abbie Chatfield was the runner up in The Bachelor and, departing with wonderfully bad grace, has left the hapless bachelor behind and launched into her own media career.

Abby Chatfield Interview with

PM Anthony Albanese

The good, the bad and the downright ugly: Our media is broken

We have become accustomed, not too happily, to a form of political journalism in which opinion and news have increasingly merged, blunting the essential distinction between political commentary and detached objectivity. With journalists now routinely writing both news and opinion, this distinction has become impossibly blurred, undermining the impartiality and accuracy on which political journalism depends.

Nowhere is this decline more apparent than in the response to two very different, yet equally significant, events in our election-tuned political landscape recently. Firstly, the much-anticipated interest rate cut of .25%, the first in four years, and second, the Albanese Government’s announcement of its signature health policy with the largest investment in Medicare and bulk-billing since the Hawke Labor Government created Medicare 40 years ago. Both these announcements, you might think, would be considered unalloyed good news for the Albanese Government and covered extensively given their importance. Well, think again.

The interest rate cut had barely been announced, let alone acknowledged as a welcome relief for mortgage holders, before it was promptly swept away in a tide of confected media negativity. This “line-ball decision” as the Australian Financial Review incorrectly termed it, it was a unanimous Reserve Bank board decision, was quickly depicted as a “one off” or, as the ABC proclaimed “miserly, as good as it gets”. The long-awaited rate cut soon became lost in reports of the Reserve Bank governor, Michele Bullock, having “ruled out another pre-election interest rate cut” – which she had not actually said. Bullock, quite properly, refused to be drawn on when the next interest rate cut might be. To do otherwise would have risked the markets acting in advance. If anything, Bullock’s speech left open the prospect of further interest rate cuts this year, which the markets are already pricing in. Not so for our troubled media, whose perennial fear of appearing “biased” by reporting good news objectively as just that — good news — had created a negative out of a positive.

And, as if that wasn’t bad enough, the media’s response to the government’s Medicare expansion announcement was even worse – perverse to the point of surreal. Albanese announced a centrepiece of the government’s re-election campaign, a $8.5 billion commitment to extend bulk-billing from 11 million to 26 million people, with nine out of 10 GP visits to be bulk billed by 2030. This is the largest investment in Medicare in its 40-year history. The government’s policy not only expands bulk-billing rates and availability, but also increases GP training and nursing scholarships. It was fully costed and articulated over the next five years. The Coalition, on the other hand, is a policy void and in health policy it had done nothing – there has been no policy development, no consultation with medical providers about best practice, and no budget details.

Nevertheless, despite the absence of policy work, the Coalition immediately claimed it would match the government’s Medicare expansion “dollar for dollar” – note the careful wording, a dollar value not the individual elements in it. This reflex political response, designed only to head off the obvious electoral positive for the government in prioritising universal health care, was scarcely worth a journalistic footnote. Yet it was this, not the government’s announcement but the Coalition’s five-word response to it, that became the story – not just in one or two media reports, but in all. The same framing, the same wording, and — hey presto! — the Albanese Government’s Medicare announcement had been “neutralised”, “the wind taken out of its sails”, and the government’s policy on Medicare was gifted to the Coalition by a media struggling to maintain any semblance of independent thought. “Labor and the Coalition have pledged to raise GP bulk billing,” The Conversation generously “both-sided” what was, in fact, the government’s policy. Opposition Leader Peter Dutton has since promised to fund the Coalition’s putative Medicare expansion by sacking 36,000 public servants.

What should have been a day of focused media coverage and analysis of the largest financial commitment to Medicare since it was created became instead a false equivalence between Labor’s detailed and costed policy, and the Coalition’s cheap knock-off, devoid of any substance other than Dutton’s own hot air. To equate those two — one a carefully designed policy and the other a five-word political response to it — is a shameful derogation of journalistic responsibility, even more so as we approach an election. Little wonder that a recent opinion poll showed most people are unaware of the Albanese Government’s policy achievements in office – a poll commented on without a hint of self-reflection by the same media that had failed to report them.

And so, it was a breath of fresh air to hear an informed and engaged conversation with Albanese from an entirely unexpected quarter, radio presenter and podcaster, Abbie Chatfield. It was a smart move by Albanese to sit down for a 1½-hour with Chatfield, whose podcast It’s a lot is one of the most popular in Australia, and within 24 hours more than 30,000 people had already listened in. Chatfield puts every jaded, cynical, tired old legacy journalist to shame. She’s interested, she wants to hear more, she doesn’t interrupt, she’s not trying to get a gotcha moment, and as a result Albanese is at his best – clear about the government’s policies and direction, aware of what more needs to be done, and full of hope for the future.

At last, media worth listening to.

Pearls and Irritations, John Menadue’s Public Policy Journal Republished from The Echo, February 27,2025

American Politics

Heather Cox Richardson from Letters from an American <heathercoxrichardson@substack.com>

Lately, political writers have called attention to the tendency of billionaire Elon Musk to refer to his political opponents as “NPCs.” This term comes from the gaming world and refers to a nonplayer character, a character that follows a scripted path and cannot think or act on its own, and is there only to populate the world of the game for the actual players. Amanda Marcotte of Salon notes that Musk calls anyone with whom he disagrees an NPC, but that construction comes from the larger environment of the online right wing, whose members refer to anyone who opposes Donald Trump’s agenda as an NPC.

In The Cross Section, Paul Waldman notes that the point of the right wing’s dehumanization of political opponents is to dismiss the pain they are inflicting. If the majority of Americans are not really human, toying with their lives isn’t important—maybe it’s even LOL funny to pretend to take a chainsaw to the programs on which people depend. “We are ants, or even less,” Waldman writes, “bits of programming to be moved around at Elon’s whim. Only he and the people who aspire to be like him are actors, decision-makers, molding the world to conform to their bold interplanetary vision.”Waldman correctly ties this division of the world into the actors and the supporting cast to the modern-day Republican Party’s longstanding attack on government programs. After World War II, large majorities of both parties believed that the government must work for ordinary Americans by regulating business, providing a basic social safety net like Social Security, promoting infrastructure projects like the interstate highway system, and protecting civil rights that guaranteed all Americans would be treated equally before the law. But a radical faction worked to undermine this “liberal consensus” by claiming that such a system was a form of socialism that would ultimately make the United States a communist state.

By 2012, Republicans were saying, as Representative Paul Ryan did in 2010, that “60 Percent of Americans are ‘takers,’ not ‘makers.’” In 2012, Ryan had been tapped as the Republican vice presidential candidate. As Waldman recalls, in that year, Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney told a group of rich donors that 47% of Americans would vote for a Democrat “no matter what.” They were moochers who “are dependent upon government, who believe that they are victims, who believe the government has a responsibility to care for them, who believe that they are entitled to health care, to food, to housing, to you-name-it.”

As Waldman notes, Musk and his team of tech bros at the Department of Government Efficiency are not actually promoting efficiency: if they were, they would have brought auditors and would be working with the inspectors general that Trump fired and the Government Accountability Office that is already in place to streamline government. Rather than looking for efficiency, they are simply working to zero out the government that works for ordinary people, turning it instead to enabling them to consolidate wealth and power.Today’s attempt to destroy a federal government that promotes stability, equality, and opportunity for all Americans is just the latest iteration of that impulse in the United States.

The men who wrote the Declaration of Independence took a revolutionary stand against monarchy, the idea that some people were better than others and had a right to rule. They asserted as “self-evident” that all people are created equal and that God and the laws of nature have given them certain fundamental rights. Those include—but are not limited to—life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. The role of government was to make sure people enjoyed these rights, they said, and thus a government is legitimate only if people consent to that government. For all that the founders excluded Indigenous Americans, Black colonists, and all women from their vision of government, the idea that the government should work for ordinary people rather than nobles and kings was revolutionary.

From the beginning, though, there were plenty of Americans who clung to the idea of human hierarchies in which a few superior men should rule the rest. They argued that the Constitution was designed simply to protect property and that as a few men accumulated wealth, they should run things. Permitting those without property to have a say in their government would allow them to demand that the government provide things that might infringe on the rights of property owners.

By the 1850s, elite southerners, whose fortunes rested on the production of raw materials by enslaved Black Americans, worked to take over the government and to get rid of the principles in the Declaration of Independence. As Senator James Henry Hammond of South Carolina put it: “I repudiate, as ridiculously absurd, that much lauded but nowhere accredited dogma of Mr. Jefferson that ‘all men are born equal.’”

“We do not agree with the authors of the Declaration of Independence, that governments ‘derive their just powers from the consent of the governed,’” enslaver George Fitzhugh of Virginia wrote in 1857. “All governments must originate in force, and be continued by force.” There were 18,000 people in his county and only 1,200 could vote, he said, “[b]ut we twelve hundred…never asked and never intend to ask the consent of the sixteen thousand eight hundred whom we govern.”

Northerners, who had a mixed economy that needed educated workers and thus widely shared economic and political power, opposed the spread of the South’s hierarchical system. When Congress, under extraordinary pressure from the pro-southern administration, passed the 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act that would permit enslavement to spread into the West and from there, working in concert with southern slave states, make enslavement national, northerners of all parties woke up to the looming loss of their democratic government.A railroad lawyer from Illinois, Abraham Lincoln, remembered how northerners were “thunderstruck and stunned; and we reeled and fell in utter confusion. But we rose each fighting, grasping whatever he could first reach—a scythe—a pitchfork—a chopping axe, or a butcher’s cleaver” to push back against the rising oligarchy. And while they came from different parties, he said, they were “still Americans; no less devoted to the continued Union and prosperity of the country than heretofore.” Across the North, people came together in meetings to protest the Slave Power’s takeover of the government, and marched in parades to support political candidates who would stand against the elite enslavers.

Apologists for enslavement denigrated Black Americans and urged white voters not to see them as human. Lincoln, in contrast, urged Americans to come together to protect the Declaration of Independence. “I should like to know if taking this old Declaration of Independence, which declares that all men are equal upon principle and making exceptions to it where will it stop?… If that declaration is not the truth, let us get the Statute book, in which we find it and tear it out!”

Northerners put Lincoln into the White House, and once in office, he reached back to the Declaration—written “four score and seven years ago”—and charged Americans to “resolve that…this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom—and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

The victory of the United States in the Civil War ended the power of enslavers in the government, but new crises in the future would revive the conflict between the idea of equality and a nation in which a few should rule.In the 1890s the rise of industry led to the concentration of wealth at the top of the economy, and once again, wealthy leaders began to abandon equality for the idea that some people were better than others. Steel baron Andrew Carnegie celebrated the “contrast between the palace of the millionaire and the cottage of the laborer,” for although industrialization created “castes,” it created “wonderful material development,” and “while the law may be sometimes hard for the individual, it is best for the race, because it insures the survival of the fittest in every department.”

Those at the top were there because of their “special ability,” Carnegie wrote, and anyone seeking a fairer distribution of wealth was a “Socialist or Anarchist…attacking the foundation upon which civilization rests.” Instead, he said, society worked best when a few wealthy men ran the world, for “wealth, passing through the hands of the few, can be made a much more potent force for the elevation of our race than if it had been distributed in small sums to the people themselves.”

As industrialists gathered the power of the government into their own hands, people of all political parties once again came together to reclaim American democracy. Although Democrat Grover Cleveland was the first to complain that “[c]orporations, which should be the carefully restrained creatures of the law and the servants of the people, are fast becoming the people’s masters,” it was Republican Theodore Roosevelt who is now popularly associated with the development of a government that took power back for the people.

Roosevelt complained that the “absence of effective…restraint upon unfair money-getting has tended to create a small class of enormously wealthy and economically powerful men, whose chief object is to hold and increase their power. The prime need is to change the conditions which enable these men to accumulate power which it is not for the general welfare that they should hold or exercise.” Roosevelt ushered in the Progressive Era with government regulation of business to protect the ability of individuals to participate in American society as equals.

The rise of a global economy in the twentieth century repeated this pattern. After socialists took control of Russia in 1917, American men of property insisted that any restrictions on their control of resources or the government were a form of “Bolshevism.” But a worldwide depression in the 1930s brought voters of all parties in the U.S. behind President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s “New Deal for the American people.”

He and the Democrats created a government that regulated business, provided a basic social safety net, and promoted infrastructure in the 1930s. Then, after Black and Brown veterans coming home from World War II demanded equality, that New Deal government, under Democratic president Harry Truman and then under Republican president Dwight D. Eisenhower, worked to end racial and, later, gender hierarchies in American society.

That is the world that Elon Musk and Donald Trump are dismantling. They are destroying the government that works for all Americans in favor of using the government to concentrate their own wealth and power.

And, once again, Americans are protesting the idea that the role of government is not to protect equality and democracy, but rather to concentrate wealth and power at the top of society. Americans are turning out to demand Republican representatives stop the cuts to the government and, when those representatives refuse to hold town halls, are turning out by the thousands to talk to Democratic representatives.

Thousands of researchers and their supporters turned out across the country in more than 150 Stand Up for Science protests on Friday. On Saturday, International Women’s Day, 300 demonstrations were organized around the country to protest different administration policies. Senator Bernie Sanders (I-VT) is drawing crowds across the country with the “Fighting Oligarchy: Where We Go From Here” tour, on which he has been joined by Shawn Fain, president of the United Auto Workers.“

Nobody voted for Elon Musk,” protestors chanted at a Tesla dealership in Manhattan yesterday in one of the many protests at the dealerships associated with Musk’s cars. “Oligarchs out, democracy in.”—

Notes:https://www.nytimes.com/2025/02/16/opinion/ezra-klein-podcast-congress-audio-essay.htmlhttps://www.salon.com/2025/02/24/what-elon-musks-on-workers-owes-to-gamergate/

What ‘Harriet The Spy’ Taught Me And Other Millennials Who Could Not Be Silenced

Story by Molly Wadzeck Kraus

At 11 years old, I was a victim of a secret three-way call. My so-called friend at the time kept pressuring me to reveal what I really thought about our mutual friend. After a lengthy interrogation, frustrated and cornered, I finally blurted out an offhand comment about how her constant giggling and “sunshine” personality were annoying.

The response was immediate and brutal: laughter — not from one, but two sixth-grade girls — echoed down the landline. I was devastated. My private thoughts, which I never intended to share, were weaponized against me. They were exposed, ridiculed and used as ammunition. That betrayal cut deep.

It wouldn’t be the last time my unfiltered observations about the world or people would get me into trouble. Have you ever read the comment section of a woman’s writing on the internet? Or checked her inbox after sharing an honest, vulnerable thought? It’s often an unforgiving place. As an adult, online responses to my thoughts have pushed me away from online spaces for months at a time.

Around the same time as that tween hazing ritual, “Harriet the Spy” — a classic coming-of-age film starring Michelle Trachtenberg as the film’s namesake — was released. The film, based on the 1964 novel by Louise Fitzhugh, follows 11-year-old Harriet M. Welsch, an aspiring writer whose early craft is as an amateur spy. She spends her days observing the lives of the people around her, taking notes on their behaviors and secrets in a notebook. However, when her private thoughts and observations are accidentally revealed to her friends, they turn against her.

Trachtenberg, 39, was found dead in her New York City apartment on Wednesday; her co-stars Rosie O’Donnell, Blake Lively, Kenan Thompson and more have paid tribute online. Fans have flooded social media with appreciation for her work — especially other millennials like me who recognized themselves in her characters.

Harriet, like so many girls at that age, craved to understand the world around her. She wasn’t merely a nosy girl; she sought understanding — of strangers and of the people in her life. I was no different. I had my diaries, journals and secret binders, each one a place I tried to untangle the mess of adolescence. It was in those notebooks that I began to make sense of the chaos, interrogating the conversations I transcribed and the behaviors I described, searching for clues about my acceptance, my place in the world and the shifting tides of friendship and identity. In those pages, I began to piece together who I was — or at least who I hoped to become.

After bullying escalated in sixth grade, I transferred to a new school; my mom was a teacher there. As the new girl, my only power was my ability to observe and reflect, carefully walking a tightrope between cliques, watching for subtle signs of loyalty or discord, taking note of jean choices or jewelry or shoes. What would it take to fit in here? Who did I need to look out for? Who could I trust?

So, like Harriet, I began my own secret spy career. Like Harriet, I was an observer — insatiably curious, easily obsessed and stubborn to fault. For me, writing became a way to process the complexities of human behavior.

Over the years, I learned the importance of being discerning with my language. How much of a story should I tell? Which details should I leave out, and which should I highlight? These decisions shape the narrative, just as our interpretations of the people in our lives shape the characters in our stories. This was what felt so real about Harriet: She simply wrote what she saw, what she thought, and what she felt. She was the epitome of a first draft.

As an adult, I understand the deeper question Harriet was really grappling with: Are girls allowed to be their authentic selves and still be valued? To observe the world around us, to question, to write, and to express those thoughts — can we truly do that and avoid fallout?

The summer before seventh grade, I typed up a dossier on every significant peer from the past two school years. Each section was filled with raw, unfiltered thoughts — good, bad, innocuous and boring. I printed it on dot matrix paper and folded it accordion-style into a storage bin where it has stayed ever since (currently in my basement in a larger storage container with other adolescent creations). It wasn’t intended for anyone else to read. It was my personal record, my way of processing how my friend groups had fallen apart and how the people around me had become unpredictable.

Occasionally, I remember it, I come back to it for nostalgia’s sake, and I’m always shocked at how accurate my memory is of the events I wrote down right as or after they happened. Or is this just part of the same story I’ve always been telling? My memory is clear and accurate because it’s what I want to remember. Because I made it part of my story when I was writing it. It’s true to me, but it’s not necessarily true to those I wrote about.

It is a harsh lesson Harriet has to learn: that just because something she wrote is true to her doesn’t make it the end of the story.

As Harriet navigated the fallout from her revelations, she began to reflect on whether she could have both friends and be a spy. “If I had to choose,” she wondered, “I’d pick spy. Maybe you’re not allowed to have both.”

Special correspondent travelling from Canberra to Perth

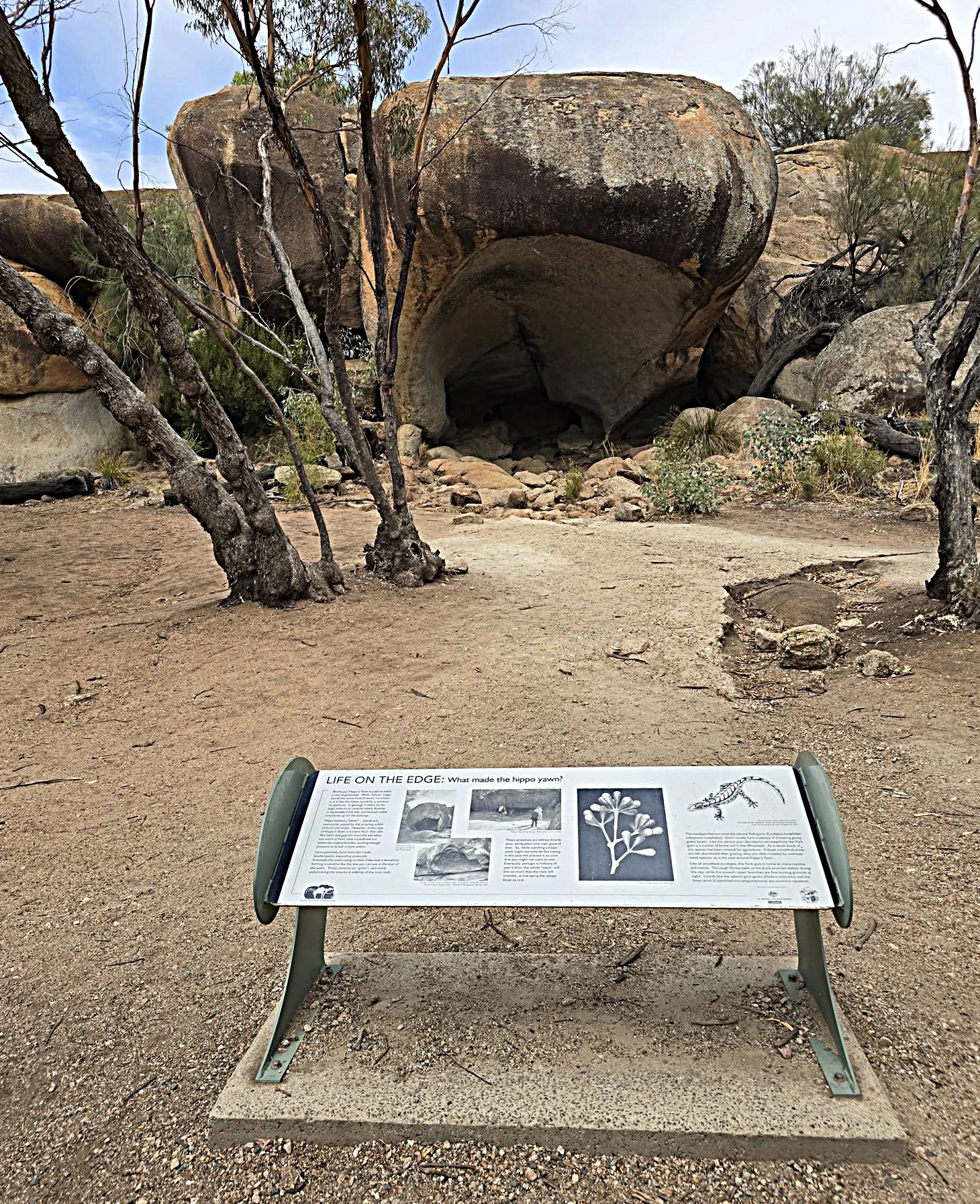

I have travelled the Nullabor several times now, from and to Perth, starting with my 9th birthday and it is only now i have realised one thing and learnt a new thing about it. The stretch from Ceduna to the border is really not that big or hard to do – last time we made the mistake of shopping up in Ceduna in prep for there being no shops for a while, but hit the border within a day so had to camp up and cook or peel or freeze everything to be allowed to take it across the border. This time we knew and made sure we had nothing we couldn’t take over. However, what I realised then is that the stretch from the border to Norseman, the next big place is in fact the longer and more boring stretch. It seemed to take ages to get there. Luckily this time we arrived when the one supermarket was open, and we could stock up again. The new thing I now know is that you DO NOT have to go via either Esperance or Kalgoorlie – there IS in fact a road straight through the middle from Norseman to Hyden along the Granite Woodlands trail. It is not sealed but in the dry, is perfectly fine in a 2WD and despite being unsealed it is quicker than either of the regular routes. What is strange is that looking on maps you cannot see the road! However, if you put in Norseman to Perth it shows up. Very weird but we are so glad we took the road, as it runs through the biggest remaining Mediterranean climate woodlands on earth (16m hectares – size of England), the breakaways and Wave Rock.

The Special Correspondent has named all the photos, or described the circumstances under which they were taken. I have not done this in most cases as the images are often self-explanatory. However, this batch includes a rain spotted windshield where: ‘Of course having read that the Norseman Hyden road is fine in the dry, it started to rain.’

The hippos yawn at Katter Kich (Hyden Rock). Wave Rock, one part of Katter Kich. Bit muddy by now! First time we’ve seen Aboriginal cave painting first hand.

Boddington – a fabulous playground, park and art, these are made from tyres! Mama chook personified!

The smell of these trees was wonderful, different from the gums over east.

The free campsites where the magnificent bus can be parked – alone on one site – until someone parked right next to them in the middle of the night!

VARIETY Mar 18, 2025 6:00am PT

Banijay U.K. Signs Development Deal With Ellie Wood’s Clearwood Films, Sets Adaptation of Barbara Pym Novel ‘Excellent Women’ as First Project

By Alex Ritman

Banijay U.K. has signed a development deal with award-winning producer Ellie Wood (“The Dig,” “Stonehouse”) and her company Clearwood Films and, as the first project, acquired rights to Barbara Pym’s classic 1953 novel “Excellent Women” with an option to develop further Pym books.

Under the terms of the deal, Clearwood will have access to funding to develop ideas and treatments as well as support from central Banijay U.K. resources including finance, legal and business affairs. Once greenlit, Clearwood has the option to partner with Banijay U.K. companies to co-produce. It follows on from a first look deal between Banijay Rights, Banijay’s distribution arm, and Clearwood Films, which ran from 2019. Banijay Rights will continue to distribute Clearwood projects.

“Ellie is a brilliant producer with an established reputation for creating standout, high quality drama,” said Banijay U.K. CEO Patrick Holland. “Banijay Rights have had a successful first look deal in place with Clearwood, working with Ellie on projects including Stonehouse, and we are delighted to be backing her vision.”

https://imasdk.googleapis.com/js/core/bridge3.688.0_en.html#fid=goog_767445738The video player is currently playing an ad.

Added Wood: “I’m thrilled to be working with Patrick and continuing Clearwood Films’ partnership with the wider Banijay family. I’m particularly excited to be developing the novels of one of my favourite authors, the inimitable Barbara Pym. Just as Jilly Cooper’s Rivals gave us a ‘Cooperverse’, I look forward to creating a ‘Pymverse’ and bringing this iconic author’s uniquely British tales of comic observation and unrequited love not only to her legions of fans but also to a wider TV audience.”

Upcoming Clearwood projects include an as-yet unannounced single scripted project for a linear broadcaster while Wood is executive producer on Film4‘s adaptation of Deborah Levy’s novel “Hot Milk,” starring Emma Mackey, Fiona Shaw and Vicky Krieps, which recently premiered at the Berlinale. Meanwhile, “49 Days,” a political drama by acclaimed writer John Preston, based on the tumultuous short-lived premiership of Liz Truss, backed by Banijay is also in development.

Wood previously produced the multiple BAFTA-nominated Netflix film “The Dig,” starring Carey Mulligan, Ralph Fiennes, Lily James and Johnny Flynn. In 2023, she produced “Stonehouse,” starring Matthew MacFadyen and Keeley Hawes, for ITV/Britbox.

Courgette Again

Another lunch with different company, and a few different meals to record – sides of broccoli, and mashed potato – both delicious; the steak, and beautifully served peppermint tea.

Maud Page becomes first woman to be appointed director of Art Gallery of New South Wales

By Hannah Story

Maud Page has been announced as the next director of the Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW), the first woman to lead the state institution in its 154-year history.

“To be the first woman is pretty fantastic,” Page tells ABC Arts.

Page, who is currently the gallery’s deputy director and director of collections, takes on the role next week, replacing Michael Brand, who resigned in October, after 13 years at the helm. She is only the 10th director in the gallery’s history.

Page partly attributes the 154-year wait for a woman to lead the gallery to the long tenures of former directors, including Edmund Capon, who ran the gallery for more than 33 years.

“I think the times are also right,” she says. “It’s our time.”

Page has worked at AGNSW since 2017, after previously working as deputy director and senior curator of Pacific art at the Queensland Art Gallery/Gallery of Modern Art (QAGOMA) in Brisbane, and as a lecturer in museum studies at the University of Sydney.

Her appointment as director follows a marked shift in the number of women leading state galleries across Australia.

According to the second Countess Report, released in 2019 and charting the period 2014–18, only 12.5 per cent of the director or CEO-level roles at state galleries were held by women. By 2024, with the release of the third report, charting 2018-22, that number had improved to 50 per cent.

Page also notes in the past it was rare to see internal candidates considered for the top job.

Early media speculation raised Page as a potential frontrunner, as well as Lisa Slade from the Art Gallery of South Australia, and international candidates Melissa Chiu from the Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum in the US, and Australian Suhanya Raffel from M+ in Hong Kong.

“People coming in from the outside are always shinier, and I know that the competition was fierce,” Page says.

Particularly so because of the gallery’s status among art-lovers worldwide: it’s in the world’s top 30 most visited art museums.

“It’s an institution that’s just opened a new building,” she says. “We’ve got an incredible collection, such a great staff base … So, I knew [the directorship] would be really, really contested. I had to really work very hard at it.”

The power of art

As the leader of AGNSW, Page wants to emphasise the “transformative power” of art.

“I really do think that museums and galleries are social spaces, and I really believe in the civic nature of institutions,” she says.

“I would just love for more people to use it in that way, so that people can walk through our threshold and really see the value of art.”

Page recently worked on the Djamu Youth Justice program, which, since 2017, has seen artists conduct workshops with young people in the justice system in NSW.

“Initially, [the young people] were a bit like, ‘Why would we do this?'” she says.

But by the end of the workshops they were “experiencing something different and valuing it”.

“Seeing what has happened to those young [people] has been, for me, a life-changing experience. I really love seeing those very real instances where art can make a difference.”

Page’s own appreciation of the power of art stems from being taken by her family to galleries and museums when she was growing up. She recalls being amazed by the work of 18th-century French painter Jean-Antoine Watteau, as well as Bull’s Head by Picasso — a found object artwork made from a bicycle seat and handlebars.

“I think when you’re younger, you gravitate towards those big names, and you see the incredibleness of [their work],” she says. “And then as you get older, that expands out.”

Now, Page is particularly invested in the work of local artists at all stages of their careers, from emerging to established.

“They’re people that are making a difference and that are creating incredible work, aesthetically, subject-wise, materially,” she says.

“The breadth of our industry is so fantastic; that’s what makes it exciting. There’s never a dull moment.”

She’s particularly excited by the gallery’s diversity of spaces — with its new building Naala Badu and its restored neoclassical original building Naala Nura — and how it celebrates both historical and contemporary collections.

She’s excited about the way those spaces showcase new work from contemporary NSW artists, for example Archibald-winning Sydney artist Mitch Cairns; or the works of women artists who have been overlooked, such as 83-year-old abstract painter Lesley Dumbrell.