Tasma Walton I am Nannertgarrook Simon & Schuster (Australia) | S&S Bundyi, April 2025.

Thank you, Net Galley, and Simon & Schuster, for providing me with this uncorrected proof for review.

Tasma Walton’s I am Nannertgarroock is so far removed from my recall of her as the pleasant enough young police officer in Blue Heelers that I suffered elements of the dissonance that, at a level far beyond my experience, must impact indigenous Australians at levels unimaginable every day of their lives. It was a good way to begin reading this heartbreaking novel with its beautiful images of Nannertgarrook’s life in her own setting, where indeed she is Nannertgarrook, and the revulsion for a vastly different life after her captivity when her being is brutally questioned with her renaming as Eliza or no-one.

The first half of the book is a revelation that bears rereading. Walton’s rendition of indigenous life is beautifully woven, with women’s business in the forefront, but the coming together of families after their individual activities are completed, warm, loving, and full of humour. Walton draws us into lives that are complete with domestic and public tasks and events, together with the overarching world of Indigenous spirituality, the land and sea, and its inhabitants. On the outskirts of these lives, harmonious with the environment and with each other, hover the sealers. They bludgeon the seals with little concern for anything but their livelihood, and eventually bludgeon an Indigenous mother and child, leaving their bodies for the Indigenous community to care for and mourn.

The second half of the book takes place in the sealers’ environment – brutal, uncaring, with values far removed from those experienced though Nannertgarrook’s early life. She and other women from her community are captures, enslaved, bear the sealers’ children and are given English names. Although I would have been satisfied with less of this period, its brutality being well described throughout Nannertgarrook’s lengthy life on various islands with her sealer captor. However, some of the detail provides valuable insight into the superior Indigenous hunting practices, their links with the land and their family and community feelings and beliefs. Records of the time, taken by an insensitive white researcher who appears on the island, provide yet more material about relationships between white and Indigenous people. Unsurprisingly, although outwardly benign in contrast with the sealers’ behaviour, they are brutal in their own way. Nannertgarrook’s eventual departure from the island when her captor falls ill is far from the return home she dreamed about, again demonstrating the benign brutality of white denial of her personhood.

There is a glossary of indigenous words, which is useful. However, the words become part of the reader’s language long before this. As awkward as I found this sometimes, the words being so far from my knowledge, they played a part in drawing me into the novel. After all, the Indigenous groups brought together on the sealers’ islands, being from different communities also had to communicate in unfamiliar language. They ached to understand each other well beyond any desire to be part of the language that would give them entry to the sealers’ world. Walton says that the next novel she writes will not be so harrowing, and I look forward to it. However, I feel privileged to have been invited into this one, with its mixture of beauty and suffering.

It seems appropriate to place the photo of this mural, from a high school wall in Collie after this review of Walton’s book. In addition, I have concentrated on some of the indigenous sites and interests I experienced in Perth.

Sculptures on the beach, Fremantle Western Australia

The first sculpture pictured demonstrates the role of Indigenous culture in this exhibition.

Sculptures pictured above are: Alan Seymour – Nyaung-gan; Tony Jones – Rottnest Blues; Sakura Motomura – Dazzle; Melanie Maclou – Ocean Dancer: crimson allure; MM- OD; Johannes Pannekoek – Elegy in Motion 1; Mandy Hawkehead – Intonation (musical sound tubes, depicting an ocean melody); Sam Hopkins – Beyond the surface.

Beach scenes nearby

Wellington Dam – with the largest dam mural, as then Premier Mark McGowan introduced it in February 2021.

Collie Murals

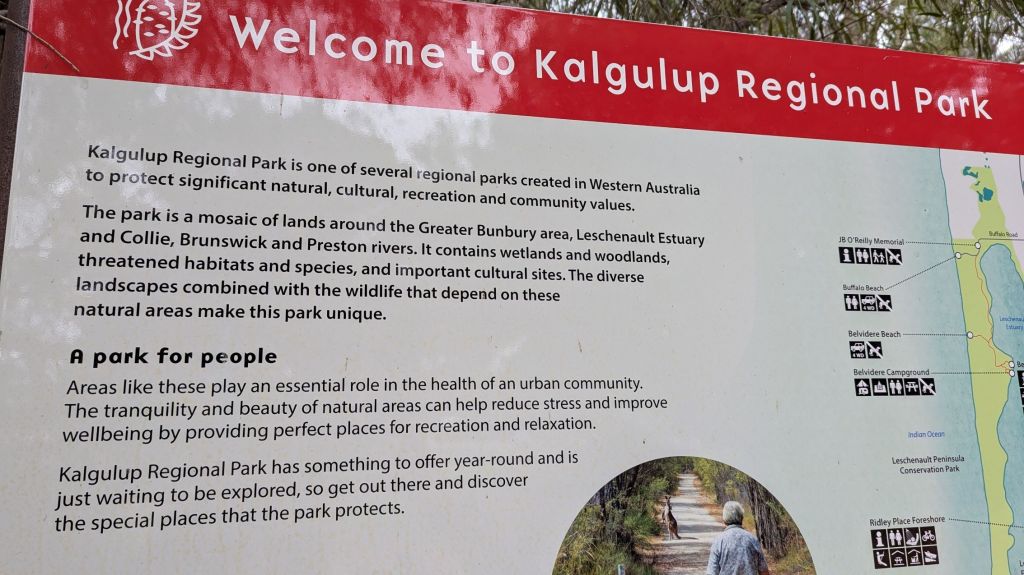

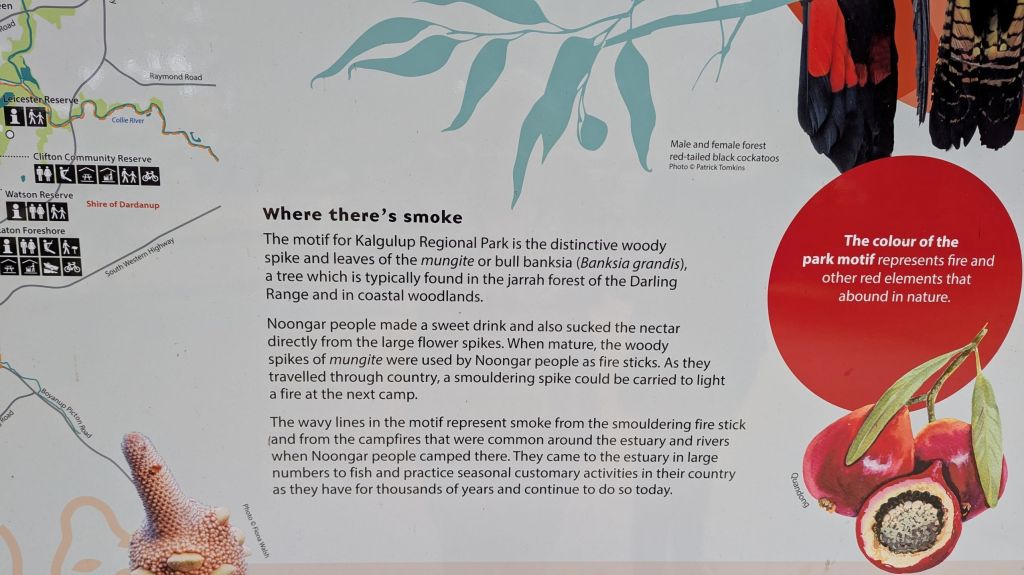

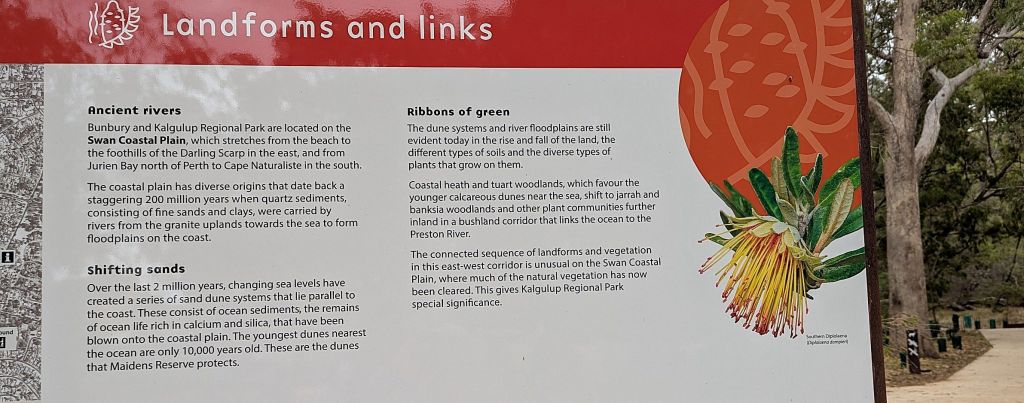

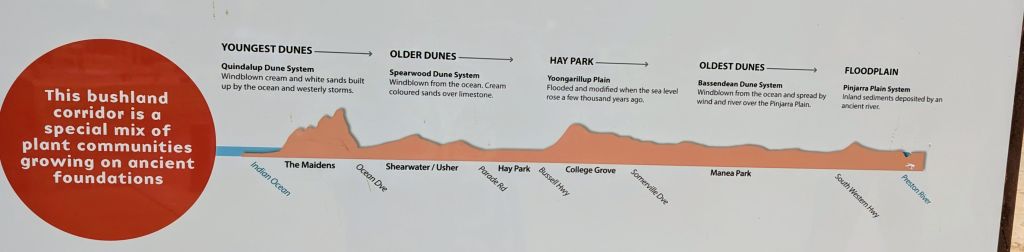

Kalgulup Regional Park, Bunbury

Bush walk to the Two Maidens

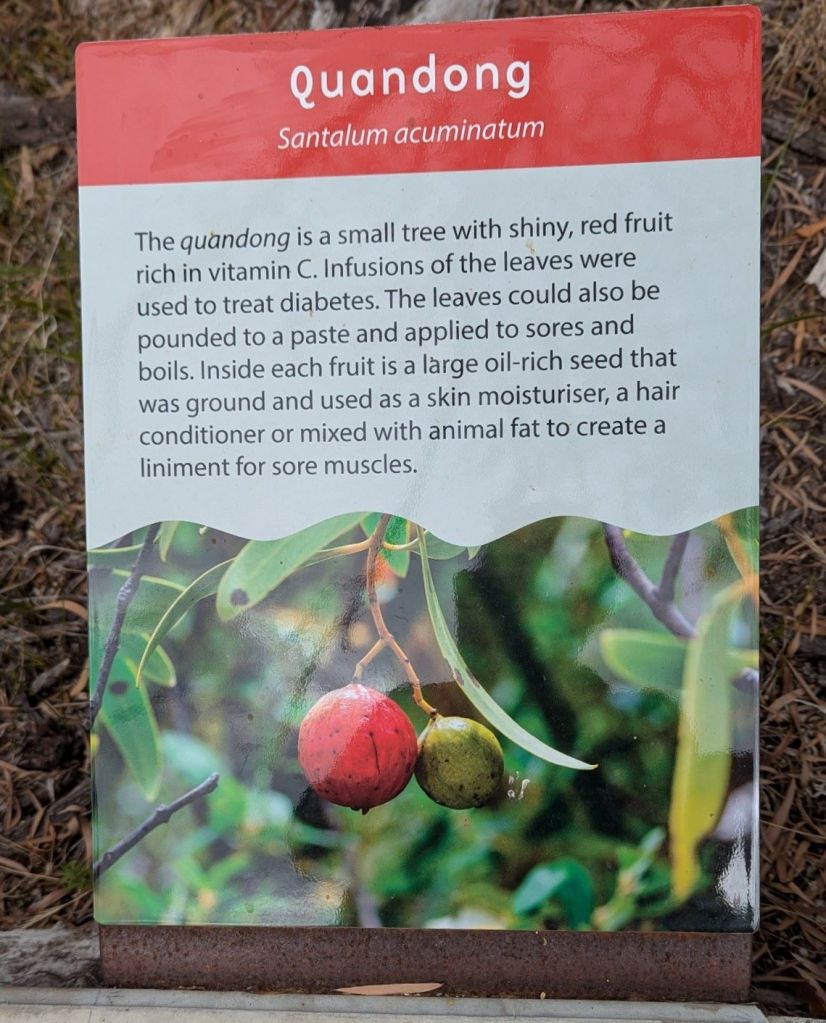

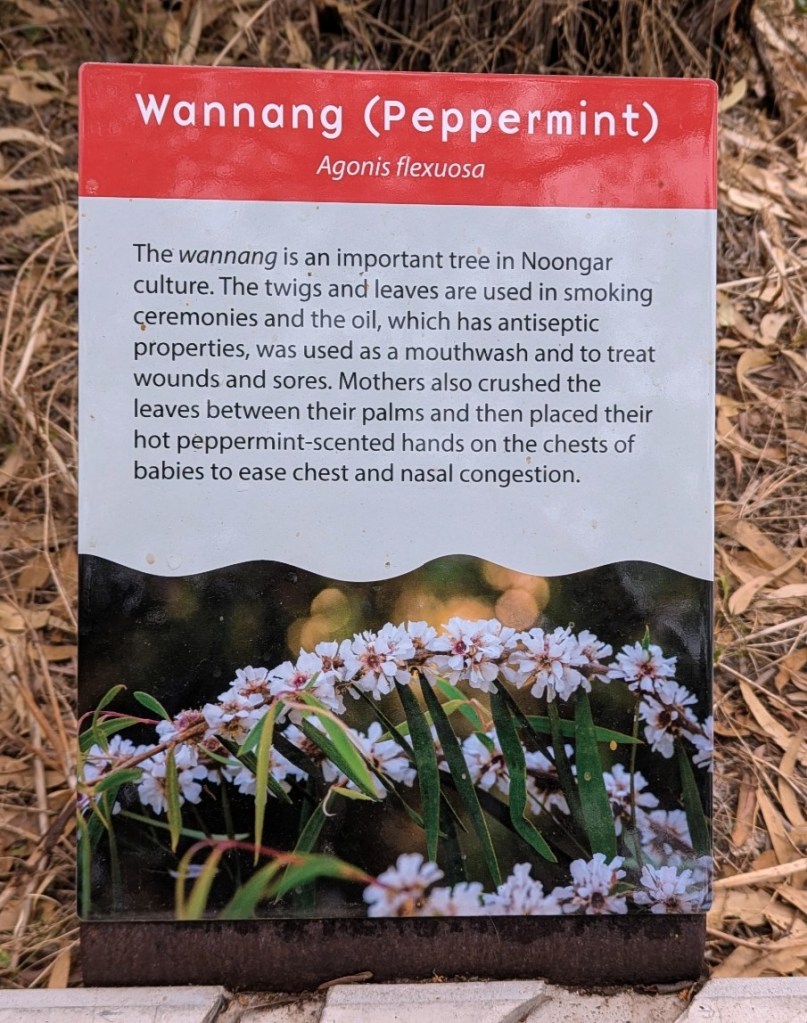

Information about the indigenous use of the trees passed on the walk to the top

Indigenous TAFE numbers skyrocket on back of government’s fee-free enrolments

Dechlan Brennan – October 4, 2024

First Nations enrolments in TAFE courses now make up more than 5 per cent of all enrolments, with the federal government saying their Fee-Free TAFE initiative continues to exceed targets.

As of July this year there were 500,000 TAFE enrolments, with 26,500 enrolments being First Nations people – accounting for 5.3 per cent of all enrolments.

This is despite Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people accounting for 3.8 per cent of the population.

Speaking exclusively to National Indigenous Times, Labor Senator Jana Stewart said the importance of an education couldn’t be underestimated.

“The data tells us that high levels of education are linked to improve health outcomes, better literacy, better health literacy and overall wellbeing,” the Mutthi Mutthi and Wamba Wamba woman from North-West Victoria said.

“It leads to better economic opportunities; so not just your employment outcomes, but also your ability to be able to negotiate income and working conditions improve.”

Ms Stewart said it was also vitally important to give young mob vision and inspiration for what is possible.

“When you see more Blak nurses or more Blak aged care workers…it just really cements the path about what’s possible for you,” the Senator said.

“I think setting the bar high for our mob is a really important thing, because I’ve got every confidence that they reach it every time.”

The Senator currently chairs the Joint Standing Committee on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Affairs, taking over from Pat Dodson, where she fronted an inquiry considering barriers and opportunities to support economic prosperity for First Nations people.

The Inquiry into economic self-determination and opportunities for First Nations Australians comes after the release of the Murru Waaruu economic outcomes report, which called for a critical shift in public policy to effectively support the economic empowerment of Indigenous Australians.

Senator Stewart said when it came to the benefits of education, there were no surprises.

“It means you’re also able to make more informed decisions about how you preserve and protect culture and cultural knowledge,” she said.

“And it also means that…you kind of [are] more empowered and feel more confident in taking on the world.”

Originally from Swan Hill on the south bank of the Murray River, the youngest First Nations woman to be elected in Federal Parliament espoused the benefits of TAFE courses, saying she remembers her Nan, Aunties and Uncles completing such qualifications in her former years.

“I think the other factor for me that I think about is that for a long time, our Mob have thought that university and getting qualifications for university have felt unattainable,” she said.

“And so then for lots of our mob, they’ve gone through the TAFE system.”

She noted the courses are more accessible, as well as not going for as long as traditional university courses.

“They’re not as expensive; and in this case, we’re talking about fee-free TAFE. So, it’s free,” she said.

Furthermore, courses are often run by Aboriginal-Community-Controlled Organisations (ACCOs), allowing prospective future First Nations students the peace of mind that they will receive a culturally safe education.

As a result, many students are being trained by other successful First Nations people who have excelled in their role.

“How deadly is it for our mob to actually be the trained professional in that situation?” Senator Stewart said.

Cindy Lou eats out in Bunbury, Western Australia

Barn- Zee

Barn- Zee is a successful – not only is the food delicious but the staff are friendly and efficient – indigenous owned and operated cafe. We had coffees, a toasted sandwich with beautifully melted cheese, and vanilla slices. The last were too tempting. I am glad that I do not live nearby.

Hello Indian

Hullo Indian is a pleasant restaurant which relies on the flavour and quality of its food – and rightly so. Our dishes were excellent, the butter chicken with its distinctive flavour – generous succulent portions of chicken combined with a delicious sauce was my favourite. The vegetable curry was also a winner, and the beef curry was returned to again and again. The samosas to begin were large and served with tamarind sauce and greens – another success. Staff were pleasant and the chef, as well as his culinary skills, was friendly .

Little Spencer Street Bakehouse

Amongst the many coffee places open on Good Friday, Spencer Street Bakehouse offered indoor and outdoor seating, and provided good coffees, and a generous well-cooked breakfast from and extensive menu..

Full of Beanz Coffee

This is a drive through coffee place with a good menu, and lovely staff. The coffees were great, and the savoury muffin very filling and pleasant. Even better, the walk was similar to our regular Canberra walk, as far as distance goes. Alas, our Canberra walk does not include lakes and pelicans.

The Water’s Edge

We had some delicious pastas- the special, chicken Carbonara (the request for chili was agreed immediately and the portion provided, generous); spaghetti and meat balls; and spaghetti, garlic and prawns (the request to omit the chili was granted without fuss). This is a friendly restaurant, in a lovely location, with a good menu and readiness to meet customers’ requests that is exemplary. The wagtail was a bonus.

Benesse

Our last coffees in the Bunbury area, before returning to Perth on the superb train trip from Mandurah to Perth.

Cindy Lou eats out in Perth

Petition

This restaurant has attracted me for several years. However, I’ve not eaten there, so when it was open on Easter Sunday, it was even more of a wonderful surprise.

The food was delicious, starting with olives, fetta and warm bread with a whipped flavoured butter. We then had octopus- marinaded with chili and other ingredients, so the chili was delicate rather than overwhelming and ham hock croquettes, roast pumpkin and broccolini. The atmosphere was casual and friendly, with people ordering by choice, rather than adhering to entree, main etc. Next to us two oysters, followed by chicken was ordered. On the other side, more oysters, a ceviche and roast pumpkin. The noisy men, further afield, went through the whole menu probably. We left before they would have ordered dessert.

I can see Petition being a restaurant we go to on future trips to Perth.

Samuels on Mill

Last time we were here, we ate with friends. This time, we chose a little more wisely from the small dishes. Service is friendly, and the food very good, although I thought that the risotto could have been more flavoursome. It was enhanced by the goats cheese and zucchini on top, but the rice portion was rather bland. The standout was the pumpkin. The prawns, and the stracciatella dishes with which we began were also excellent.

Samuels Bar

A shared club sandwich and chips at Samuels bar was generous and delicious. The mocktails were pleasant but not inspiring.

Riverside Cafe

Coffee on the Swan River is always a treat. On this occasion we celebrated PM Anthony Albanese’s success in ensuring that Canadians can continue to enjoy vegemite from an Australian business there.

Picnic at Kings Park

The Blue Cat took us to Kings Park where we had simple picnic in beautiful surrounds. The latter are far more picturesque than the former.

One Sixty, Murray Street

This was a simple breakfast before going to the Western Australian Museum to see a virtual reality exhibition of the Kimberley. The service was quick and pleasant, the coffees good, and the food tasty.

WA Museum Cafe

This was a mixed experience. The quiches and toasties were pleasant and the coffees good. However, a badly heated pie (the recipient’s first for forty years) was a disappointment.

Our last coffees in Perth were at Basilica. The service was very friendly and efficient, and the atmosphere lively. Basilica is set just off St Georges Terrace, near Mill Street.

Art Gallery Bunbury

An exhibition by indigenous artists was a highlight of our trip to Bunbury.

Galleries’ commitment to children’s art is always an aspect that I believe is essential, and this gallery has promoted children’s art through provision of materials and a wall display.

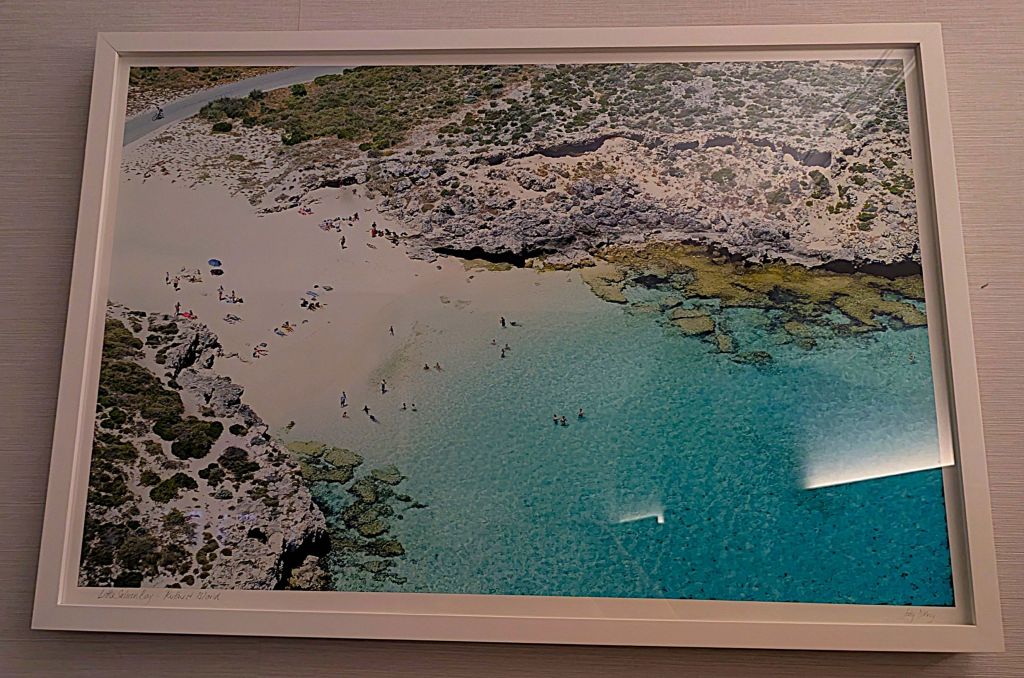

Photograph on our hotel bedroom wall

Little Salmon Bay, Rottnest Island, Jodie D’Arcy

Jodie is the daughter of a woman with whom I worked illustrating correspondence school material years ago. It is wonderful to see Jodie’s work find a larger audience!

Heather Cox Richardson from Letters from an American <heathercoxrichardson@substack.com> Unsubscribe1 9 Apr 2025, 15:35 (2 days ago)   to me to me |

Tonight I had the extraordinary privilege of speaking at the anniversary of the lighting of the lanterns in Boston’s Old North Church, which happened 250 years ago tonight. Here’s what I said:

Two hundred and fifty years ago, in April 1775, Boston was on edge. Seven thousand residents of the town shared these streets with more than 13,000 British soldiers and their families. The two groups coexisted uneasily.

Two years before, the British government had closed the port of Boston and flooded the town with soldiers to try to put down what they saw as a rebellion amongst the townspeople. Ocean trade stopped, businesses failed, and work in the city got harder and harder to find. As soldiers stepped off ships from England onto the wharves, half of the civilian population moved away. Those who stayed resented the soldiers, some of whom quit the army and took badly needed jobs away from locals.

Boston became increasingly cut off from the surrounding towns, for it was almost an island, lying between the Charles River and Boston Harbor. And the townspeople were under occupation. Soldiers, dressed in the red coats that inspired locals to insult them by calling them “lobsterbacks,” monitored their movements and controlled traffic in and out of the town over Boston Neck, which was the only land bridge from Boston to the mainland and so narrow at high tide it could accommodate only four horses abreast.

Boston was a small town of wooden buildings crowded together under at least eight towering church steeples, for Boston was still a religious town. Most of the people who lived there knew each other at least by sight, and many had grown up together. And yet, in April 1775, tensions were high.

Boston was the heart of colonial resistance to the policies of the British government, but it was not united in that opposition. While the town had more of the people who called themselves Patriots than other colonies did—maybe 30 to 40 percent—at least 15% of the people in town were still fiercely loyal to the King and his government. Those who were neither Patriots nor Loyalists just kept their heads down, hoping the growing political crisis would go away and leave them unscathed.

It was hard for people to fathom that the country had come to such division. Only a dozen years before, at the end of the French and Indian War, Bostonians looked forward to a happy future in the British empire. British authorities had spent time and money protecting the colonies, and colonists saw themselves as valued members of the empire. They expected to prosper as they moved to the rich lands on the other side of the Appalachian Mountains and their ships plied the oceans to expand the colonies’ trade with other countries.

That euphoria faded fast.

Almost as soon as the French and Indian War was over, to prevent colonists from stirring up another expensive struggle with Indigenous Americans, King George III prohibited the colonists from crossing the Appalachian Mountains. Then, to pay for the war just past, the king’s ministers pushed through Parliament a number of revenue laws.

In 1765, Parliament passed the Stamp Act, requiring the payment of a tax on all printed material—from newspapers and legal documents to playing cards. It would hit virtually everyone in the North American colonies. Knowing that local juries would acquit their fellow colonists who violated the revenue acts, Parliament took away the right to civil trials and declared that suspects would be tried before admiralty courts overseen by British military officers. Then Parliament required colonials to pay the expenses for the room and board of British troops who would be stationed in the colonies, a law known as the Quartering Act.

But what Parliament saw as a way to raise money to pay for an expensive war—one that had benefited the colonists, after all—colonial leaders saw as an abuse of power. The British government had regulated trade in the empire for more than a century. But now, for the first time, the British government had placed a direct tax on the colonists without their consent. Then it had taken away the right to a trial by jury, and now it was forcing colonists to pay for a military to police them.

Far more than money was at stake. The fight over the Stamp Act tapped into a struggle that had been going on in England for more than a century over a profound question of human governance: Could the king be checked by the people?

This was a question the colonists were perhaps uniquely qualified to answer. While the North American colonies were governed officially by the British crown, the distance between England and the colonies meant that colonial assemblies often had to make rules on the ground. Those assemblies controlled the power of the purse, which gave them the upper hand over royal officials, who had to await orders from England that often took months to arrive. This chaotic system enabled the colonists to carve out a new approach to politics even while they were living in the British empire.

Colonists naturally began to grasp that the exercise of power was not the province of a divinely ordained leader, but something temporary that depended on local residents’ willingness to support the men who were exercising that power.

The Stamp Act threatened to overturn that longstanding system, replacing it with tyranny.

When news of the Stamp Act arrived in Boston, a group of dock hands, sailors, and workers took to the streets, calling themselves the Sons of Liberty. They warned colonists that their rights as Englishmen were under attack. One of the Sons of Liberty was a talented silversmith named Paul Revere. He turned the story of the colonists’ loss of their liberty into engravings. Distributed as posters, Revere’s images would help spread the idea that colonists were losing their liberties.

The Sons of Liberty was generally a catch-all title for those causing trouble over the new taxes, so that protesters could remain anonymous, but prominent colonists joined them and at least partly directed their actions. Lawyer John Adams recognized that the Sons of Liberty were changing the political equation. He wrote that gatherings of the Sons of Liberty “tinge the Minds of the People, they impregnate them with the sentiments of Liberty. They render the People fond of their Leaders in the Cause, and averse and bitter against all opposers.”

John Adams’s cousin Samuel Adams, who was deeply involved with the Sons of Liberty, recognized that building a coalition in defense of liberty within the British system required conversation and cooperation. As clerk of the Massachusetts legislature, he was responsible for corresponding with other colonial legislatures. Across the colonies, the Sons of Liberty began writing to like-minded friends, informing them about local events, asking after their circumstances, organizing.

They spurred people to action. By 1766, the Stamp Act was costing more to enforce than it was producing in revenue, and Parliament agreed to end it. But it explicitly claimed “full power and authority to make laws and statutes…to bind the colonies and people of America…in all cases whatsoever.” It imposed new revenue measures.

News of new taxes reached Boston in late 1767. The Massachusetts legislature promptly circulated a letter to the other colonies opposing taxation without representation and standing firm on the colonists’ right to equality in the British empire. The Sons of Liberty and their associates called for boycotts on taxed goods and broke into the warehouses of those they suspected weren’t complying, while women demonstrated their sympathy for the rights of colonists by producing their own cloth and drinking coffee rather than relying on tea.

British officials worried that colonists in Boston were on the edge of revolt, and they sent troops to restore order. But the troops’ presence did not calm the town. Instead, fights erupted between locals and the British regulars.

Finally, in March 1770, British soldiers fired into a crowd of angry men and boys harassing them. They wounded six and killed five, including Crispus Attucks, a Black man who became the first to die in the attack. Paul Revere turned the altercation into the “Boston Massacre.” His instantly famous engraving showed soldiers in red coats smiling as they shot at colonists, “Like fierce Barbarians grinning o’er their Prey; Approve the Carnage, and enjoy the Day.”

Parliament promptly removed the British troops to an island in Boston Harbor and got rid of all but one of the new taxes. They left the one on tea, keeping the issue of taxation without representation on the table. Then, in May 1773, Parliament gave the East India Tea Company a monopoly on tea sales in the colonies. By lowering the cost of tea in the colonies, it meant to convince people to buy the taxed tea, thus establishing Parliament’s right to impose a tax on the colonies.

In Boston, local leaders posted a citizen guard on Griffin’s Wharf at the harbor to make sure tea could not be unloaded. On December 16, 1773, men dressed as Indigenous Americans boarded three merchant ships. They broke open 342 chests of tea and dumped the valuable leaves overboard.

Parliament closed the port of Boston, stripped the colony of its charter, flooded soldiers back into the town, and demanded payment for the tea. Colonists promptly organized the Massachusetts Provincial Congress and took control of the colony. The provincial congress met in Concord, where it stockpiled supplies and weapons, and called for towns to create “minute men” who could fight at a moment’s notice.

British officials were determined to end what they saw as a rebellion. In April, they ordered military governor General Thomas Gage to arrest colonial leaders Samuel Adams and John Hancock, who had left Boston to take shelter with one of Hancock’s relatives in the nearby town of Lexington. From there, they could seize the military supplies at Concord. British officials hoped that seizing both the men and the munitions would end the crisis.

But about 30 of the Sons of Liberty, including Paul Revere, had been watching the soldiers and gathering intelligence. They met in secret at the Green Dragon Tavern to share what they knew, each of them swearing on the Bible that they would not give away the group’s secrets. They had been patrolling the streets at night and saw at midnight on Saturday night, April 15, the day before Easter Sunday, that the general was shifting his troops. They knew the soldiers were going to move. But they didn’t know if the soldiers would leave Boston by way of the narrow Boston Neck or row across the harbor to Charlestown. That mattered because if the townspeople in Lexington and Concord were going to be warned that the troops were on their way, messengers from Boston would have to be able to avoid the columns of soldiers.

The Sons of Liberty had a plan. Paul Revere knew Boston well—he had been born there. As a teenager, he had been among the first young men who had signed up to ring the bells in the steeple of the Old North Church. The team of bell-ringers operated from a small room in the tower, and from there, a person could climb sets of narrow stairs and then ladders into the steeple. Anyone who lived in Boston or the surrounding area knew well that the steeple towered over every other building in Boston.

On Easter Sunday, after the secret watchers had noticed the troop movement, Revere traveled to Lexington to visit Adams and Hancock. On the way home through Charlestown, he had told friends “that if the British went out by Water, we would shew two Lanthorns in the North Church Steeple; & if by Land, one, as a Signal.” Armed with that knowledge, messengers could avoid the troops and raise the alarm along the roads to Lexington and Concord.

The plan was dangerous. The Old North Church was Anglican, Church of England, and about a third of the people who worshipped there were Loyalists. General Thomas Gage himself worshiped there. But so did Revere’s childhood friend John Pulling Jr., who had become a wealthy sea captain and was a vestryman, responsible for the church’s finances. Like Revere, Pulling was a Son of Liberty. So was the church’s relatively poor caretaker, or sexton, Robert Newman. They would help.

Dr. Joseph Warren lived just up the hill from Revere. He was a Son of Liberty and a leader in the Massachusetts Provincial Congress. On the night of April 18, he dashed off a quick note to Revere urging him to set off for Lexington to warn Adams and Hancock that the troops were on the way. By the time Revere got Warren’s house, the doctor had already sent another man, William Dawes, to Lexington by way of Boston Neck. Warren told Revere the troops were leaving Boston by water. Revere left Warren’s house, found his friend John Pulling, and gave him the information that would enable him to raise the signal for those waiting in Charlestown. Then Revere rowed across the harbor to Charleston to ride to Lexington himself. The night was clear with a rising moon, and Revere muffled his oars and swung out of his way to avoid the British ship standing guard.

Back in Boston, Pulling made his way past the soldiers on the streets to find Newman. Newman lived in his family home, where the tightening economy after the British occupation had forced his mother to board British officers. Newman was waiting for Pulling, and quietly slipped out of the house to meet him.

The two men walked past the soldiers to the church. As caretaker, Newman had a key.

The two men crept through the dark church, climbed the stairs and then the ladders to the steeple holding lanterns—a tricky business, but one that a caretaker and a mariner could manage—very briefly flashed the lanterns they carried to send the signal, and then climbed back down.

Messengers in Charlestown saw the signal, but so did British soldiers. Legend has it that Newman escaped from the church by climbing out a window. He made his way back home, but since he was one of the few people in town who had keys to the church, soldiers arrested him the next day for participating in rebellious activities. He told them that he had given his keys to Pulling, who as a vestryman could give him orders. When soldiers went to find Pulling, he had skipped town, likely heading to Nantucket.

While Newman and Pulling made their way through the streets back to their homes, the race to beat the soldiers to Lexington and Concord was on. Dawes crossed the Boston Neck just before soldiers closed the city. Revere rowed to Charlestown, borrowed a horse, and headed out. Eluding waiting officers, he headed on the road through Medford and what is now Arlington.

Dawes and Revere, as well as the men from Charleston making the same ride after seeing the signal lanterns, told the houses along their different routes that the Regulars were coming. They converged in Lexington, warned Adams and Hancock, and then set out for Concord. As they rode, young doctor Samuel Prescott came up behind them. Prescott was courting a girl from Lexington and was headed back to his home in Concord. Like Dawes and Revere, he was a Son of Liberty, and joined them to alert the town, pointing out that his neighbors would pay more attention to a local man.

About halfway to Concord, British soldiers caught the men. They ordered Revere to dismount and, after questioning him, took his horse and turned him loose to walk back to Lexington. Dawes escaped, but his horse bucked him off and he, too, headed back to Lexington on foot. But Prescott jumped his horse over a stone wall and got away to Concord.

The riders from Boston had done their work. As they brought word the Regulars were coming, scores of other men spread the news through a system of “alarm and muster” the colonists had developed months before for just such an occasion. Rather than using signal fires, the colonists used sound, ringing bells and banging drums to alert the next house that there was an emergency. By the time Revere made it back to the house where Adams and Hancock were hiding, just before dawn on that chilly, dark April morning, militiamen had heard the news and were converging on Lexington Green.

So were the British soldiers.

When they marched onto the Lexington town green in the darkness just before dawn, the soldiers found several dozen minute men waiting for them. An officer ordered the men to leave, and they began to mill around, some of them leaving, others staying. And then, just as the sun was coming up, a gun went off. The soldiers opened fire. When the locals realized the soldiers were firing not just powder, but also lead musket balls, most ran. Eight locals were killed, and another dozen wounded.

The outnumbered militiamen fell back to tend their wounded, and about 300 Regulars marched on Concord to destroy the guns and powder there. But news of the arriving soldiers and the shooting on Lexington town green had spread through the colonists’ communication network, and militiamen from as far away as Worcester were either in Concord or on their way. By midmorning the Regulars were outnumbered and in battle with about 400 militiamen. They pulled back to the main body of British troops still in Lexington.

The Regulars headed back to Boston, but by then militiamen had converged on their route. The Regulars had been awake for almost two days with only a short rest, and they were tired. Militiamen fired at them not in organized lines, as soldiers were accustomed to, but in the style they had learned from Indigenous Americans, shooting from behind trees, houses, and the glacial boulders littered along the road. This way of war used the North American landscape to their advantage. They picked off British officers, dressed in distinct uniforms, first. By that evening, more than three hundred British soldiers and colonists lay dead or wounded.

By the next morning, more than 15,000 militiamen surrounded the town of Boston. The Revolutionary War had begun. Just over a year later, the fight that had started over the question of whether the king could be checked by the people would give the colonists an entirely new, radical answer to that question. On July 4, 1776, they declared the people had the right to be treated equally before the law, and they had the right to govern themselves.

Someone asked me once if the men who hung the lanterns in the tower knew what they were doing. She meant, did they know that by that act they would begin the steps to a war that would create a new nation and change the world.

The answer is no. None of us knows what the future will deliver.

Paul Revere and Robert Newman and John Pulling and William Dawes and Samuel Prescott, and all the other riders from Charlestown who set out for Lexington after they saw the signal lanterns in the steeple of Old North Church, were men from all walks of life who had families to support, businesses to manage. Some had been orphaned young, some lived with their parents. Some were wealthy, others would scrabble through life. Some, like Paul Revere, had recently buried one wife and married another. Samuel Prescott was looking to find just one.

But despite their differences and the hectic routine of their lives, they recognized the vital importance of the right to consent to the government under which they lived. They took time out of their daily lives to resist the new policies of the British government that would establish the right of a king to act without check by the people. They recognized that giving that sort of power to any man would open the way for a tyrant.

Paul Revere didn’t wake up on the morning of April 18, 1775, and decide to change the world. That morning began like many of the other tense days of the past year, and there was little reason to think the next two days would end as they did. Like his neighbors, Revere simply offered what he could to the cause: engraving skills, information, knowledge of a church steeple, longstanding friendships that helped to create a network. And on April 18, he and his friends set out to protect the men who were leading the fight to establish a representative government.

The work of Newman and Pulling to light the lanterns exactly 250 years ago tonight sounds even less heroic. They agreed to cross through town to light two lanterns in a church steeple. It sounds like such a very little thing to do, and yet by doing it, they risked imprisonment or even death. It was such a little thing…but it was everything. And what they did, as with so many of the little steps that lead to profound change, was largely forgotten until Henry Wadsworth Longfellow used their story to inspire a later generation to work to stop tyranny in his own time.

What Newman and Pulling did was simply to honor their friendships and their principles and to do the next right thing, even if it risked their lives, even if no one ever knew. And that is all anyone can do as we work to preserve the concept of human self-determination. In that heroic struggle, most of us will be lost to history, but we will, nonetheless, move the story forward, even if just a little bit.

And once in a great while, someone will light a lantern—or even two—that will shine forth for democratic principles that are under siege, and set the world ablaze.

—

Notes:

https://boston1775.blogspot.com/2007/07/bostons-population-in-july-1775.html

https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/british-army-boston

https://www.masshist.org/database/viewer.php?item_id=98

https://www.masshist.org/database/99

Rule of Law – Joyce Vance

People value the Rule of Law because it takes some of the edge off the power that is necessarily exercised over them in a political community. In various ways, being ruled through law, means that power is less arbitrary, more predictable, more impersonal, less peremptory, less coercive even.”

In his 2010 book, The Rule of Law, Tom Bingham wrote that, at bottom, the rule of law provides much-needed predictability in the conduct of our lives and businesses. In other words, the rule of law is far more than just a matter of legal philosophy. It has a practical impact on the economy and our financial well-being, for instance. People can invest and do business because they understand the rules that will be applied to those transactions. Understanding the practical importance of the rule of law should perk up some people who might otherwise be nodding off, given the title of this post. Bear with me; I promise there is more than an academic point to what you’re about to read.

Bingham is more properly Sir Thomas Bingham. He was a high-ranking British civil judge, the Master of the Rolls, before becoming Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales, the head of the judiciary. He also served as the Senior Law Lord of the United Kingdom. In other words, he was well situated to discuss the rule of law. His book is readable and accessible for people of all backgrounds, should you want more of his thinking.

Unlike many terms we deploy with precision in our legal system, terms like “due process” or “equal protection,” there isn’t a single commonly accepted definition of the rule of law. To Bingham, “the Rule of Law is one of the ideals of our political morality and it refers to the ascendancy of law as such and of the institutions of the legal system in a system of governance.” Less formally, I would suggest that it means people who live under a rule of law system are protected by the law because everyone, including government officials and government offices, has to follow it. In a rule of law system, people know what the law is—it’s publicly available in written form, and everyone is on notice of the rules. It’s enforced equally against all people and administered by an independent judiciary. No kings. As we used to say with certainty pre-Trump, no man is above the law.

That’s the problem. Even this high-level explanation of the rule of law is sufficient to illustrate what we already know: that Trump is attacking it. He has been from the get-go, and encouraged along by some regrettable Supreme Court rulings, he’s now out in full force. It’s more than just an attack on some pretty words lawyers use; it’s a fundamental attack on our way of life. Legal principles that seem removed from our daily lives can matter, and here, they matter deeply. It’s why we should all have a baseline understanding of them. And it’s why I was so encouraged to see people out protesting on Saturday for “due process” and the rule of law, something I wouldn’t have expected to see so widely a few months ago.

The English philosopher John Locke (1632-1704) also wrote about the rule of law. In a 1689 volume of his Two Treatises of Government, he emphasized the public’s right to know what the law is, writing in an era where the law was more whimsical than the stability, for instance, the advance knowledge of what constitutes a crime, that we take for granted today. He wrote that “established standing Laws, promulgated and known to the People” were critical, contrasting them with a government that ruled through “extemporary Arbitrary Decrees.” That’s something we all understand in this moment.

Locke used the word arbitrary in this context to mean laws that weren’t fixed and established so that everyone knew what they were and there could be no fudging when it came to what people could and could not do. In Locke’s view, a ruler was arbitrary if he imposed measures with no notice, just making up the law as he went along. When there is no firm law to refer to, only the unpredictability of arbitrariness, people have nothing to rely on for conducting their daily affairs. Locke put it like this in 1689: Without the rule of law, people were subject to “sudden thoughts, or unrestrain’d, and till that moment unknown Wills without having any measures set down which may guide and justifie their actions.” In Locke’s view, predictability and certainty were essential if people were to live together. It made sense in the 1600s and it makes sense today.

What are citizens’ obligations in a rule of law system? Each of us has to follow the rules, even when we don’t agree with them, and be accountable if we violate them.

In a functioning rule of law system, the law protects everyone equally because people know what the law is, understand what they are obligated to do and refrain from doing, and can have confidence in how they will be treated when they have disputes with others. It’s the framework that lets people live and prosper together without resorting to violence to resolve every dispute, Hatfield and McCoy style. It’s why people from other countries come to the U.S. to invest, do business, and live. The rule of law is something we simultaneously take for granted and can’t live without, at least not in the way we are used to living.

One significant feature of the rule of law in our country is that it isn’t only available to the wealthy and the powerful. In the United States, criminal defendants in felony cases are guaranteed the right to counsel under a 9-0 1963 decision, Gideon v. Wainwright. Although there is nothing equivalent in civil cases, legal aid groups and pro bono organizations sponsored by bar associations provide some access to counsel for people who cannot afford it. Lawyers often take plaintiffs’ cases, everything from car accidents to mass torts, expecting to be paid only if they’re able to recover on behalf of their clients. We could do better, but there is broad access to the legal system and it has greatly improved over time.

Our system, although imperfect, has largely worked well enough to hold people’s trust and to give us the confidence and certainty that we needed to reap the benefits of the rule of law. The courts work if people trust them to take the rule of law seriously and protect it. That means having an independent judiciary that is transparent and that conducts itself with integrity.

All of this, of course, explains the seismic shift of Trumpism. It explains why presidents shouldn’t exceed their constitutional powers and why courts and Congress should act expeditiously to hold them accountable when they do. It also underscores why the courts, and individual judges, should always act with unquestionable integrity, so that in a moment where confidence in the courts is essential, it is there in abundance. The judiciary must be independent, not beholden to private interests or under the thumb of others in government. Its rulings and reasoning should be transparent. Otherwise, how can people who are removed from the courts trust them to uphold the rule of law?

That is the danger of the moment we live in. There are some encouraging signs—Democrats in Congress are rallying. The lower courts, and this past weekend the Supreme Court are imposing checks on the administration, but only when they are warranted. But there are still serious concerns about the supine Congress and Trump’s efforts to stifle dissent in government, the press, private businesses, and public organizations. The institutions, it turns out, are only as strong as the people who populate them. In some places we see courage and determination to protect the rule of law. Other places, not so much.

If the rule of law fails, it’s not just words. It’s the bedrock stability that protects our way of life. In other words, it’s not just a shoulder shrug and a time to look away. We are, thankfully, not there yet. There are ups and downs, but the most encouraging development is public awareness, particularly focused on due process, and the understanding of how important all of this is. “Hands off my rule of law!”

Americans are increasingly doing the hard work of understanding how democracy works. You cannot save something you do not understand. Understanding why it matters is as important as understanding how it works. Share this newsletter via email, or better yet, in conversations with friends. And make sure your elected officials know that you’re paying attention, that you understand what’s happening and what’s at stake. Democracy really does die in darkness, and it’s our job to keep that from happening.

If Civil Discourse has been valuable to you, becoming a paid subscriber is the best way to support the work it takes to produce each piece. Your subscription helps keep this newsletter independent, thoughtful, and focused on what truly matters, not on clicks or outrage. If you’re able, I’d be honored to have you join the paid community. Either way, I’m delighted that you’re reading the newsletter and that we are all here together, committed to keeping the Republic.

We’re in this together,

Joyce