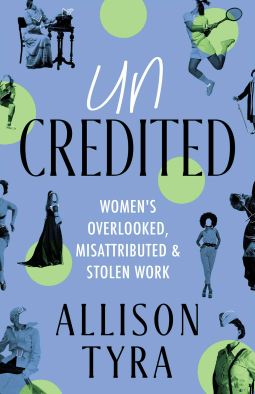

Allison Tyra Uncredited Women’s Overlooked, Misattributed, and Stolen Work Rising Action Publishing | Rising Action, May 2025.

Thank you NetGalley, for providing me with this uncorrected proof for review.

When reading research that demonstrates, yet again, the way that women and their accomplishments have been, as Alison Tyra says ‘overlooked, misattributed and stolen,’ it is difficult, heartbreaking, enraging and distressing. But it can also be enlightening and invigorating. Tyra accomplishes so much in her work, it is certainly enlightening, with its wide reach over the numerous ways in which women’s work can be “disappeared”. It also covers a vast range of professions and activities. And, if that is not enough to demonstrate the broad range of ways in which women’s contributions are unacknowledged, hidden, stolen, or misattributed, Tyra provides so many examples of locations in which these events can be found. In short, it seems that if there is a question about whose, where, what, and why women’s work has been overlooked, misattributed, and stolen, Tyra provides answers in this compelling read. See Books: Reviews for the complete review.

Rose Neal, E.D.E.N. Southworth’s Hidden Hand The Untold Story of America’s Famous Forgotten Nineteenth-Century Author The Globe Pequot Publishing Group, Inc|Lyons Press, May 2025.

Thank you, NetGalley, for providing me with this uncorrected proof for review.

E.D.E.N. Southworth, a nineteenth century writer, captured the imaginations of women wanting something different in their lives, even if it was imaginary. She was a prolific writer, published in journal and book form, raised uncomfortable issues, and introduced female characters who, it seemed, could do anything. They had to rise above the discriminatory society in which they sought to make their way. But rise they did. Rose Neal, emulating Southworth’s ability to connect with her readers has captured vividly the woman about whom she writes. Southworth was a stimulating writer, and every page of Neal’s biography exudes comparable enthusiasm about Southworth, her work, the tribulations she experienced, and so profoundly, Southworth’s world. Unlike Southworth, who at times had to curb her questing spirit to meet publishers’ demands, Neal appears to have sought out every piece of information available and used it, complimentary or not. Where none is accessible Neal’s speculation about how Southworth may have reacted or been part of an activity or group, is satisfying. See Books: Reviews for the complete review.

Discover women’s history in your area: ‘You just have to start looking’

The Guardian Sun 18 May 2025 06.00 AEST

Women are underrepresented in monuments and place names, but their stories are everywhere, says history tour guide Sita Sargeant, who shares her methods for celebrating local women’s contributions

Fewer than 4% of statues in Australia are of women. Through the monuments we build and the names we remember, we are loudly saying that women’s contributions aren’t worthy of respect. How will we ever close the gender pay gap, get more women into leadership positions and reduce violence against women if we can’t even recognise their historical contributions?

In 2021, I became so frustrated with women’s stories being overlooked and their impact underestimated that I felt I had no choice but to do something about it.

So I started sharing the stories of the incredible women who had shaped my home town of Canberra on a two-hour walking tour on Sundays. Walking tours felt like the perfect entry point. They’re accessible, engaging and fun. The stories stick because they’re tied to real places and told in ways that feel relevant. From the start, my hope was that our tours would spark curiosity and inspire people to dig deeper.

Once I started, I found that women’s stories are everywhere. You just have to start looking and, once you do, you won’t stop seeing them.

Four years on, She Shapes History is no longer just one frustrated woman with an idea. We run tours in Canberra, Sydney and Melbourne, have trained over a dozen incredible guides and welcomed thousands of people to walk with us and hear these stories. I’ve also spent six months travelling Australia to write a book about what I’ve found.

But you don’t need to start a tour to make an impact. Just choose one woman whose story resonates with you, do a bit more research on her and then share her story everywhere you go.

After years of telling women’s stories in entirely unexpected moments – from first dates to job interviews to chats with the bartender at my local pub – I’ve learned that no one will get mad at you for sharing a great story.

Look for women who have been commemorated

You’d be surprised by how many women have been commemorated – we just haven’t been taught to look for them, or learn their names.

Begin with your neighbourhood: Start where you live. Read the plaques. Look into the stories behind the names of nearby streets, parks and buildings. In Australia, women are represented in fewer than one in 10 places named after people. While that’s a pretty shocking stat, it still means thousands of women have been recognised.

Visit museums explicitly focused on sharing women’s contributions: My favourites include the Cascades Female Factory in Hobart, Her Place Women’s Museum in Melbourne, Miegunyah Historic House Museum in Brisbane, Story Bank in Maryborough and the Women’s Museum of Australia in Alice Springs.

Dive into local resources

Although more women than you might expect have been commemorated, the majority haven’t. This means you’ll need to do some digging. As you explore the history of your town or city, take note of any women’s names you come across, as well as any historical moments where women should be represented, but seem to be missing. The more research you do, the better you’ll become at spotting these gaps. Once you’ve gathered names, dive deeper into their stories.

Take a walking tour: Walking tours are an excellent shortcut for finding stories – tour guides have already done the research and selected the best ones.

Read local histories: Councils often publish town histories, self-guided walking tours and information about historical landmarks. While these resources rarely focus on just women, you’ll often find them mentioned throughout.

Visit local museums: These places are treasure troves of stories and often include perspectives overlooked by larger institutions. Don’t forget to carry cash for entry and donations, and check their hours before you visit— many are volunteer-run with limited opening times.

Explore cemeteries: Gravestones and inscriptions often tell the stories of community leaders, family matriarchs and remarkable women.

Talk to women: Ask the women in your life: your mum, grandmother, neighbours, colleagues, friends, or even the woman who runs your local pub. These conversations often uncover personal perspectives and overlooked stories you won’t find in books or archives. My favourite icebreaker (on tours, at dinner parties, even on dates) is simple: who is a woman who inspires you? Everyone can name someone.

Look for community archives: Your local library, council, or historical society might already have a history collection or community archive. Most of this isn’t online, so it’s worth popping in for a chat. Historical societies can be particularly valuable. Often run by passionate volunteers, these groups have the knowhow, resources and archives to help you dig into particular people or periods. To find your local historical society, search your town’s name and “historical society” online – something should come up.

Search online platforms: Start with Trove, the Australian Women’s Register, the Australian Dictionary of Biography and state or local archives. Don’t overlook local history blogs – they’re often packed with incredible stories you wouldn’t find elsewhere.

Preserve and share what you find

Don’t let all these incredible stories fade into obscurity – celebrate and share them with others.

Talk to the women in your life: Record interviews with women in your community and donate them to local historical societies, archives or libraries.

Write it down: Encourage women to share their stories through memoirs, essays or reflections.

Contribute to local histories: Many councils, libraries and historical societies accept photos, written stories, or oral histories, and they’re often thrilled to receive material about women. You might even find they’re working on a local project or publication you can contribute to.

Share online and in the community: Use blogs, social media, zines, podcasts or even walking tours to amplify these stories. Start Wikipedia pages for the women you find. Use art, photography or theatre to bring stories to life. Host panels, storytelling nights or film screenings celebrating women’s contributions. Use whatever tools you have to share the stories of women in your community.

Incorporate women’s stories into your everyday life: Teachers, bring women’s histories in your classroom; professionals, advocate for gender considerations in policy, health care and design; book clubs, highlight local women’s history or historical fiction. No matter what you do, there’s an opportunity to include women’s stories.

Nominate women for public commemoration: Submit the names and stories of women who deserve to be remembered to your local government for the naming of new streets, parks, schools, suburbs and other public landmarks.

Support movements for public art and place naming: Initiatives like A Monument of One’s Own or Put Her Name On It, campaign for more statues, place names and public art honouring women. Share their work, attend their events and help amplify the call for more visible recognition of women in our shared spaces.

- This is an edited extract from She Shapes History by Sita Sargeant, published by Hardie Grant Explore (A$34.99)

An Appreciation of British Women Writers from 1960-1990

Miles Leeson ·2 August at 03:52 ·

A new online course, starting in September, studying the work of Elizabeth Taylor, Anita Brookner, Angela Carter, Alice Thomas Ellis, and Rumer Godden. More details on the blog, via the link below.

Literature Cambridge Online

We will study:

Elizabeth Taylor, Angel (1957)

Rumer Godden, In this House of Brede (1969)

Angela Carter, The Bloody Chamber (1979)

Alice Thomas Ellis, The Birds of the Air (1980)

Anita Brookner, Hotel du Lac (1984)

A rare chance to study these five excellent works side by side.

Together, these novels map out different forms of post-war womanhood, overshadowed by tradition, perhaps, yet reaching – sometimes desperately, sometimes gracefully – toward real self-sufficiency and power.

Places are filling – do join us.

#womenwriters#rumergodden#angelacarter#anitabrookner

American politics

DC insider won’t minimize Trump’s repugnance | Opinion

Opinion by Robert Reich

It gets bleaker and bleaker. He’s eviscerating environmental protections. He accuses Obama of treason. He’s ripping up labor protections. He wants to privatize Social Security. He fires the head of the Bureau of Labor Statistics because he doesn’t like the job numbers. He forces the Smithsonian to take down an exhibit that includes his two impeachments. The European Union, Japan, Columbia University, and CBS are all surrendering to him.

Many of you ask me where I get my hope from, notwithstanding.

Three sources.

First, from all the young people I work with every day. They’re enormously dedicated, committed to making the world better. They’ll inherit this mess, and they’re ready to clean it up and strengthen our democracy. They also have extraordinary energy. And they’re very funny. It is impossible not to be hopeful around them.

Second, from history. We are now in a second Gilded Age that, like the first one (from the late 19th century to the start of the 20th), features wide inequalities of income and wealth, abuses of power by the oligarchs (then called “robber barons”), and a bullied and abused working class.

What happened then? The great pendulum of America swung back. The first Gilded Age was followed by what historians call the Progressive Era. Taxes were raised on the wealthy. Antitrust laws were enacted. Regulations stopped corporate malfeasance. Big money was barred from politics. And reformers — starting with Teddy Roosevelt in 1901 and extending through his fifth cousin, FDR, in 1933 — made life better for average working people.*

I don’t know exactly how or when the pendulum will swing back this time, but I am certain it will. And the regressive moral squalor of Trump and his lackeys will be swept into the dustbin of history.

My third source of optimism comes from people I meet all over America, including self-described Republicans in so-called “red” states and “red” cities, who detest what’s happening to the nation and to the world under Trump (as well as under Netanyahu and Putin).

There’s a profound decency in the sinews of America. Most Americans are generous and kind.

Opinion polls show the vast majority don’t want ICE agents disappearing their neighbors off the streets and into detention camps. They reject Trump prosecuting his so-called enemies. They think it’s wrong for him to pocket billions from crypto and other pay-to-play schemes. They don’t like him or his lackeys verbally attacking federal judges, or silencing critics.

Over 80 percent believe the minimum wage should be raised, that no full-time worker should be in poverty, that corporations should share their profits with their employees, that working people should get paid family leave, and that child care and elder care should be affordable.

I don’t want to minimize the repugnance of Trump and his sycophants. Like you, I wince when I read the news. Some days I despair.

But there are sources of hope all around us. Find them. Cling to them. Never give up.

Robert Reich is a professor of public policy at Berkeley and former secretary of labor. His writings can be found at https://robertreich.substack.com/.

*The Gilded Age, part 3 of what will be a four-part series, written by Julian Fellows, is currently being shown on television. There is detailed, animated and lengthy discussion on a Facebook site dedicated to the program. Although I do not read all the posts, I have yet to find any that refer to the way in which the “robber barons” are treating the working class, or criticism of the wealth and the way in which it is achieved.

An Assault on Truth – The Atlantic Daily

Monday, August 4, 2025.

Awarding superlatives in the Donald Trump era is risky. Knowing when one of his moves is the biggest or worst or most aggressive is challenging—not only because Trump himself always opts for the most over-the-top description, but because each new peak or trough prepares the way for the next. So I’ll eschew a specific modifier and simply say this: The past five days have been deeply distressing for the truth as a force in restraining authoritarian governance

In a different era, each of these stories would have defined months, if not more, of a presidency. Coming in such quick succession, they risk being subsumed by one another and sinking into the continuous din of the Trump presidency. Collectively, they represent an assault on several kinds of truth: in reporting and news, in statistics, and in the historical record.

On Thursday, The Washington Post revealed that the Smithsonian National Museum of American History had removed references to Trump’s record-setting two impeachments from an exhibit’s section on presidential scandals. The deletion reportedly came as part of a review to find supposed bias in Smithsonian museums. Now, referring to Presidents Andrew Johnson, Richard Nixon, and Bill Clinton, the exhibit states that “only three presidents have seriously faced removal.” This is false—Trump came closer to Senate conviction than Clinton did. The Smithsonian says the material about Trump’s impeachments was meant to be temporary (though it had been in place since 2021), and that references will be restored in an upcoming update.

If only that seemed like a safe bet. The administration, including Vice President J. D. Vance, an ex officio member of the Smithsonian board, has been pressuring the Smithsonian to align its messages with the president’s political priorities, claiming that the institution has “come under the influence of a divisive, race-centered ideology.” The White House attempted to fire the head of the National Portrait Gallery, which it likely did not have the power to do. (She later resigned.) Meanwhile, as my colleague Alexandra Petri points out, the administration is attempting to eliminate what it views as negativity about American history from National Park Service sites, a sometimes-absurd proposition.

During his first term, Trump criticized the removal of Confederate monuments, which he and allies claimed was revisionist history. It was not—preserving history doesn’t require public monuments to traitors—but tinkering with the Smithsonian is very much attempting to rewrite the official version of what happened, wiping away the impeachments like an ill-fated Kremlin apparatchik.

The day after the Post report, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting announced that it will shut down. Its demise was sealed by the administration’s successful attempt to get Congress to withdraw funding for it. Defunding CPB was a goal of Project 2025, because the right views PBS and NPR as biased (though the best evidence that Project 2025 is able to marshal for this are surveys about audience political views). Although stations in major cities may be able to weather the loss of assistance, the end of CPB could create news and information deserts in more remote areas.

When Trump isn’t keeping information from reaching Americans, he’s attacking the information itself. Friday afternoon, after the Bureau of Labor Statistics released revised employment statistics that suggested that the economy is not as strong as it had appeared, Trump’s response was to fire the commissioner of the BLS, baselessly claiming bias. Experts had already begun to worry that government inflation data were degrading under Trump. Firing the commissioner won’t make the job market any better, but it will make government statistics less trustworthy and undermine any effort by policy makers, including Trump’s own aides, to improve the economy. The New York Times’ Ben Casselman catalogs plenty of examples of leaders who attacked economic statistics and ended up paying a price for it. (Delving into these examples might provide Trump with a timely warning, but as the editors of The Atlantic wrote in 2016, “he appears not to read.”)The next day, the Senate confirmed Jeanine Pirro to be the top prosecutor for the District of Columbia. Though Pirro previously served as a prosecutor and judge in New York State, her top credential for the job—as with so many of her administration colleagues—is her run as a Fox News personality. Prior to the January 6 riot, she was a strong proponent of the false claim that the 2020 election was stolen. Her statements were prominent in a successful defamation case against Fox, and evidence in the case included a discussion of why executives yanked her off the air on November 7, 2020. “They took her off cuz she was being crazy,” Tucker Carlson’s executive producer wrote in a text. “Optics are bad. But she is crazy.”

This means that a person who either lied or couldn’t tell fact from fiction, and whom even Fox News apparently didn’t trust to avoid a false claim, is being entrusted with power over federal prosecutions in the nation’s capital. (Improbably, she still might be an improvement over her interim predecessor.)Even as unqualified prosecutors are being confirmed, the Trump White House is seeking retribution against Jack Smith, the career Justice Department attorney who led Trump’s aborted prosecutions on charges related to subverting the 2020 election and hoarding of documents at Mar-a-Lago. The Office of Special Counsel—the government watchdog that is led at the moment, for some reason, by the U.S. trade representative—is investigating whether Smith violated the Hatch Act, which bars some executive-branch officials from certain political actions while they’re on the job, by charging Trump. Never mind that the allegations against Trump were for overt behavior. Kathleen Clark, a professor of law at Washington University in St. Louis, told the Post she had never seen the OSC investigate a prosecutor for prosecutorial decisions. The charges against Trump were dropped when he won the 2024 election. If anything, rather than prosecutions being used to interfere with elections, Trump used the election to interfere with prosecutions.

This is a bleak series of events. But although facts can be suppressed, they cannot be so easily changed. Even if Trump can bowdlerize the BLS, that won’t change the underlying economy. As Democrats discovered during the Biden administration, you can’t talk voters out of bad feelings about the economy using accurate statistics; that wouldn’t be any easier with bogus ones. Trump is engaged in a broad assault on truth, but truth has ways of fighting back.

Related: Donald Trump shoots the messenger. The new dark age.

Heather Cox Richardson Letters from an American

Heather Cox Richardson from Letters from an American <heathercoxrichardson@substack.com>

Sixty years ago tomorrow, on August 6, 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act. The need for the law was explained in its full title: “An Act to enforce the fifteenth amendment to the Constitution, and for other purposes.”

In the wake of the Civil War, Americans tried to create a new nation in which the law treated Black men and white men as equals. In 1865 they ratified the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution, outlawing enslavement except as punishment for crimes. In 1868 they adjusted the Constitution again, guaranteeing that anyone born or naturalized in the United States—except certain Indigenous Americans—was a citizen, opening up suffrage to Black men. In 1870, after Georgia legislators expelled their newly seated Black colleagues, Americans defended the right of Black men to vote by adding that right to the Constitution.

All three of those amendments—the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth—gave Congress the power to enforce them. *In 1870, Congress established the Department of Justice to do just that. Reactionary white southerners had been using state laws, and the unwillingness of state judges and juries to protect Black Americans from white gangs and cheating employers, to keep Black people subservient. White men organized as the Ku Klux Klan to terrorize Black men and to keep them and their white allies from voting to change that system. In 1870 the federal government stepped in to protect Black rights and prosecute members of the Ku Klux Klan.With federal power now behind the Constitutional protection of equality, threatening jail for those who violated the law, white opponents of Black voting changed their argument against it.

In 1871 they began to say that they had no problem with Black men voting on racial grounds; their objection to Black voting was that Black men, just out of enslavement, were poor and uneducated. They were voting for lawmakers who promised them public services like roads and schools, and which could only be paid for with tax levies.

The idea that Black voters were socialists—they actually used that term in 1871—meant that white northerners who had fought to replace the hierarchical society of the Old South with a society based on equality began to change their tune. They looked the other way as white men kept Black men from voting, first with terrorism and then with grandfather clauses that cut out Black men without mentioning race by permitting a man to vote if his grandfather had, literacy tests in which white registrars got to decide who passed, poll taxes, and so on. States also cut up districts unevenly to favor the Democrats, who ran an all-white, segregationist party. By 1880 the South was solidly Democratic, and it would remain so until 1964.Southern states always held elections: it was just foreordained that Democrats would win them.Black Americans never accepted this state of affairs, but their opposition did not gain powerful national traction until after World War II.

During that war, Americans from all walks of life had turned out to defeat fascism, a government system based on the idea that some people are better than others. Americans defended democracy and, for all that Black Americans fought in segregated units, and that race riots broke out in cities across the country during the war years, and that the government interned Japanese Americans, lawmakers began to recognize that the nation could not effectively define itself as a democracy if Black and Brown people lived in substandard housing, received substandard educations, could not advance from menial jobs, and could not vote to change any of those circumstances.

Meanwhile, Black Americans and people of color who had fought for the nation overseas brought home their determination to be treated equally, especially as the financial collapse of European nations loosened their grip on their former African and Asian colonies and launched new nations.Those interested in advancing Black rights turned, once again, to the federal government to overrule discriminatory state laws. Spurred by lawyers Thurgood Marshall and Constance Baker Motley, judges used the due process clause and the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to argue that the protections in the Bill of Rights applied to the states, that is, the states could not deprive any American of equality. In 1954 the Supreme Court under Chief Justice Earl Warren, the Republican former governor of California, used this doctrine when it handed down the Brown v. Board of Education decision declaring segregated schools unconstitutional.

White reactionaries responded with violence, but Black Americans continued to stand up for their rights. In 1957 and 1960, under pressure from Republican president Dwight Eisenhower, Congress passed civil rights acts designed to empower the federal government to enforce the laws protecting Black voting.

In 1961 the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the Council of Federated Organizations (COFO) began intensive efforts to register voters and to organize communities to support political change. Because only 6.7% of Black Mississippians were registered, Mississippi became a focal point, and in the “Freedom Summer” of 1964, organized under Bob Moses, volunteers set out to register voters. On June 21, Ku Klux Klan members, at least one of whom was a law enforcement officer, murdered organizers James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner near Philadelphia, Mississippi, and, when discovered, laughed at the idea they would be punished for the murders.

That year, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which strengthened voting rights. When Black Americans still couldn’t register to vote, on March 7, 1965, in Selma, Alabama, marchers set out for Montgomery to demonstrate that they were being kept from registering. Law enforcement officers on horseback met them with clubs on the Edmund Pettus Bridge. The officers beat the marchers, fracturing the skull of young John Lewis (who would go on to serve 17 terms in Congress).

On March 15, President Johnson called for Congress to pass legislation defending Americans’ right to vote. It did. And on this day in 1965, the Voting Rights Act became law. It became such a fundamental part of our legal system that Congress repeatedly reauthorized it, by large margins, as recently as 2006.But in the 2013 Shelby County v. Holder decision, the Supreme Court under Chief Justice John Roberts struck down the provision of the law requiring that states with histories of voter discrimination get approval from the Department of Justice before they changed their voting laws. Immediately, the legislatures of those states, now dominated by Republicans, began to pass measures to suppress the vote. In the wake of the 2020 election, Republican-dominated states increased the rate of voter suppression, and on July 1, 2021, the Supreme Court permitted such suppression with the Brnovich v. Democratic National Committee decision.

Currently, the Supreme Court is considering whether a Louisiana district map that took race into consideration to draw a district that would protect Black representation is unconstitutional. About a third of Louisiana’s residents are Black, but in 2022 its legislature carved the state up in such a way that only one of its six voting districts was majority Black. A federal court determined that the map violated the Voting Rights Act, so the legislature redrew the map to give the state two majority-Black districts.

A group of “non-African American voters” immediately challenged the law, saying the new maps violated the Fourteenth Amendment because the mapmakers prioritized race when drawing them. A divided federal court agreed with their argument. Now the Supreme Court will weigh in.

Meanwhile, on July 29, Senator Raphael Warnock (D-GA) led a number of his Democratic colleagues in reintroducing a measure to restore and expand the Voting Rights Act. The bill is called the John R. Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act after the man whose skull police officers fractured on the Edmund Pettus Bridge.—Notes:https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/constance-baker-motley.htmhttps://www.oyez.org/cases/2025/24-109https://www.naacpldf.org/case-issue/louisiana-v-callais-faq/https://apnews.com/article/voting-rights-discrimination-democrats-supreme-court-gop-d4238972cbb94cb9ce02e59aae643f2c

*See Elie Mystal’s Bad Law, reviewed – Blog January 8, 2025. He has some trenchant comments on the Amendments associated with voting laws and equality.

*John Lewis The Last Interview reviewed – Blog November 17, 2021.

Canberra Writers Festival

|

| Dalton Defies Gravity: Trent Dalton in Conversation Saturday 25 October | 6.30pm National Library of Australia Presented in partnership with the ANU Meet the Author. Australia’s bestselling-author of Boy Swallows Universe, Trent Dalton, is back with a bang ‘surprise’ new book – and he wants you to be the first to hear about it. Trent shook the literary world with his embellished memoir of petty crime, drug dealing and family violence in 1980s Brisbane. The way he captured doing it tough, in a uniquely Australian way, became a cultural phenomenon and the most successful Australian-made Netflix series ever. After a series of subsequent bestselling books, Trent returns with his most personal work yet, Gravity Let Me Go, again set in Brisbane, and about a journalist obsessed with the true-crime scoop of a lifetime. Dark, occasionally terrifying, but with wonderful moments of humour, light and Dalton-sweetness, Trent shows us again why we see ourselves in his work… could the characters be us if we’d just taken a few wrong turns? In conversation with journalist, author and book enthusiast extraordinaire, Caroline Overington. |