JB Miller, Duch Riverdale Avenue Books February 2025.

Thank you, NetGalley, for providing me with this uncorrected proof for review.

What fun, I thought, as I saw the premise for this book – Diana is living in Paris, having lost her memory but recognised as Diana by a school friend. But JB Miller has given so much more to attract a much broader audience than those who miss Diana, might like to see the British royal family exposed, or want a partisan view of the William and Kate versus Harry and Meghan stories that clutter the media.

The essential Diana is no longer her appearance, although that remains attractive at times; her fashionable dress, although the white pyjamas she wears have their place on the catwalk under her spell; or her ability to speak and be heard, although that too, is sometimes successful. It is the hugging that she bestows that has a mystical quality. Somewhere Diana’s magic is intact – and possibly in this woman in her sixties who is saved from the Seine, her first words being that she is Diana.

JB Miller has woven an elegant story line with understanding of the hearts of those who miss her, those who feared or resented the public’s fascination with her while she was alive, and those for whom she became an icon after her death. Her followers, her detractors, and the royal family to which she belonged and then left behind, as well as the media, feature. All are treated with humour and sensitivity, as well as being metaphorically prodded with wonderfully sharp observations. See Books: Reviews for the complete review.

See also, below, a new publication about Diana’s and her sons’ roles in her legacy. Duch is yet another interpretation of the way in which Diana has been seen, and both publications could fit together well.

Martina Devlin Charlotte Independent Publishers Group | The Lilliput Press, August 2025.

Thank you, NetGalley, for providing me with this uncorrected proof for review.

The Charlotte Bronte of Martina Devlin’s imagination is no pure rendition of the author of the well-known Jane Eyre, Shirley and Villette and the less famous juvenilia, posthumously published, The Professor and incomplete works. She is a woman who inspires love and affection, is a sexual being, a writer of adoring letters to a married man, a censor of her sisters’ work, and while enthralled in part by her marriage, is prepared to set aside any inclination to obey when it does not suit her plans. Her Irish background is less refined than the world she knows, which is apparent when on her honeymoon she rejects her husband’s demand (based on Patrick Bronte’s wish) that she should ignore her Irish relatives. This Charlotte is seen through the eyes of Mary Bell, who after Charlotte’s death marries her widower, Arthur Bell Nicholls, and lives, not only under the shadow of the first marriage, but the continual presence through that marriage of a woman that she longed to know closely.

See Books: Reviews for the complete review. See also, below, information about Elizabeth Gaskell’s biography of Charlotte Bronte.

The Life of Charlotte Brontë

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Title page of the first edition, 1857 | |

| Author | Elizabeth Gaskell |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Genre | Biography |

| Publisher | Smith, Elder & Co. |

| Publication date | 1857 |

| Publication place | United Kingdom |

The Life of Charlotte Brontë is the posthumous biography of Charlotte Brontë by English author Elizabeth Gaskell. The first edition was published in 1857 by Smith, Elder & Co. A major source was the hundreds of letters sent by Brontë to her lifelong friend Ellen Nussey.

Gaskell had to deal with rather sensitive issues, toning down some of her material: in the case of her description of the Clergy Daughters’ School, attended by Charlotte and her sisters, this was to avoid legal action from the Rev. William Carus Wilson, the founder of the school. The published text does not go so far as to blame him for the deaths of two Brontë sisters, but even so the Carus Wilson family published a rebuttal with the title “A refutation of the statements in ‘The life of Charlotte Bronte,’ regarding the Casterton Clergy Daughters’ School, when at Cowan Bridge”.

Although quite frank in many places, Gaskell suppressed details of Charlotte’s love for Constantin Héger, a married man, on the grounds that it would be too great an affront to contemporary morals and a possible source of distress to Charlotte’s living friends, father Patrick Brontë and husband.[1] She also suppressed any reference to Charlotte’s romance with George Smith, her publisher, who was also publishing the biography. In 2017, The Guardian named The Life of Charlotte Brontë one of the 100 best nonfiction books of all time.[2]

Notes: Lane 1953, pp. 178–183; McCrum, Robert (17 April 2017). “The 100 best nonfiction books: No 63 – The Life of Charlotte Brontë by Elizabeth Gaskell (1857)”. The Guardian. Guardian News and Media Limited. Retrieved 1 January 2018.

Marie Bostwick The Book Club for Troublesome Women HarperCollins Focus | Harper Muse, April 2025.

Thank you, NetGalley, for providing me with this uncorrected proof for review.

Marie Bostwick’s book begins with her revelation about her inspiration for it – a conversation with her ninety-one-year-old mother in which Bostwick learnt that Betty Freidan’s The Feminine Mystique had, in her mother’s words, changed her life. She then describes the research she undertook, often arousing feelings of anger, but also admiration of the women facing egregious discrimination. She recognises what Freidan, and those moved by her, did for women – an excellent start to a work of fiction that introduces courageous characters who respond to the discrimination they faced. The women’s coming together, through a book club based on reading extensively and eventually sisterhood, is an engaging topic and Bostwick’s book is a fine vehicle.

My immediately positive response was to Bostwick’s use of the term ‘troublesome women.’ This is a phrase used by feminist writers, Judith Butler, Naomi Wolf, and Laurel Thatcher Ulrich to describe women who refuse to bow to the traditional concept of behaviour that would designate them ‘good’ women. There is also the phrase, ‘Well behaved women rarely make history’ on my favourite, always worn, bracelet. Clearly, Bostwick was going to write about the sorts of women I wanted to read about!

Margaret, Bitsy, Charlotte, and Viv all live in a middle-class suburb, in houses with British names, these names providing information about the size and grandeur of the house. Margaret organises a book club and is encouraged by Charlotte to introduce it with Betty Freidan’s The Feminine Mystique. Each woman responds differently to the book, or the small sections they manage to read. However, the discussion about their reactions provides the nucleus for further revelations. At the same time as the women look for inspiration to change the lives they have adopted since leaving school or college, they are 1960s women with their attention to dress, the food they will provide at their meetings and suffering with curlers in their hair so as ‘to look their best’. The juxtaposition of women and their concerns who will be so familiar to baby boomers, and their aspirations, is heartwarming.

The women’s lives change. Their developing friendships, dealing with what they more strongly identify as discrimination at work, home and in the neighbourhood, and, in turn, realising that discrimination against women stultifies all human relationships and aspirations make for a story that weaves together a group of women worth knowing, ideas that are worth thinking about, and new pathways that are tempting.

The Book Club for Troublesome Women is an enlightening read at the same time as it is a touching story. There are highs and lows that are realistically portrayed, and the ending is particularly satisfying.

The new battle of brothers: Prince William and Prince Harry and ‘upholding Diana’s true legacy’

Story by Natalie Oliveri

The long-running feud between Prince William and Prince Harry has largely been talked about in terms of their disagreements over Meghan and the fallout from the Sussexes’ royal exit.

Going hand-in-hand with their sibling rivalry growing up (which Harry documented at length in his memoir, Spare) there has been another battle playing out between the two brothers in their adult years: that is, which brother best represents their late mother, Diana.

“It’s like there’s a church schism going on, both of them seem to think that they are upholding Diana’s true legacy,” author Edward White told 9honey from his home in Kent.

The brothers are carefully choosing their royal work to align with things that are “truly important about her”, he said.

“The point of my book is that people – from different communities and backgrounds – are seeing in Diana what they want to see and the same seems to be true even of her children,” White said.

White’s book Dianaworld: An Obsession is not your traditional royal biography, instead exploring the way the royal was viewed by various groups and the mania that was created by her mere existence.

The book is an exploration of the world Diana lived in, looking at her reputation from differing perspectives and the legacy that has been created nearly 30 years on from her death.

In White’s words, the books is “a vehicle for everybody else’s neurosis and obsessions and their own sense of identities”.

“The book isn’t about Diana, it’s just about everybody else. [It’s] a book about her reputation rather than her life.”

Dianaworld: An Obsession is out now.

See the remainder of this article in Further Commentary and Articles arising from Books* and continued longer articles as noted in the blog.

9 Books About Female Friendship in Every Decade of Life

Romance has nothing on the impact of a lifelong best friend

Aug 12, 2025

Michelle Herman

As a child in Brooklyn, my spirits rose and fell on the tides of a girl named Susan’s moods and disposition. We met in 1958, when both of us were three, our mothers both pregnant with unwanted (by us) younger siblings. We were inseparable—soulmates, I would have said, if I’d known the word—for years. Eight years, to be exact. And then my family moved a half-mile away, into a different school district.

Susan was only the first of a lifelong parade of best and near-best, second-, third-, and close-but-not-best friends (I often maintained a deep bench). I think about them all, whether we’re still close (Hula) or not (Ronnie). Whether we are still in touch or not—whether they are still alive or not. I think about them all—Maria, Amy, Vicki, Debra, Marly, Kathy, et al.—far more often, and with far more feeling (sadness, gladness, longing, love, regret, nostalgia—and, in one case, hurt and grief) than I think about any of my ex-boyfriends.

The truth is that even in my youth—my boy-crazy teens, my heat-missile-seeking 20s/early 30s—my friendships have always been more crucial to me than the romances that came and went. These were the relationships I knew I could count on (until, once in a while, I couldn’t—and then it was more shattering, and harder to get over, than a failed romance). It’s no surprise that I have gravitated all my life to good stories that center friendship. Or that I’ve been writing about friendship since before I published my first story in 1979. My latest book, the essay collection If You Say So, is dedicated to the friends who’ve come into my life in the last decade. It is also populated by them—a whole community that I lucked into in my 60s, a time when it’s supposed to be practically impossible to make new friends. The title essay is about one of them. Others sweep (and spin and leap) throughout. (This is not a metaphor. We take dance classes and perform together, and much of the book takes place in the dance studio.) And since stories about women’s and girls’ friendships—unlike those about romantic love—are not a dime a dozen, here’s a list of books in which it’s friendship that matters most, in every decade of a woman’s life. See Further Commentary and Articles arising from Books* and continued longer articles as noted in the blog. for the remainder of this article. It is a terrific read about the way in which women’s friendships have been an important topic in women’s writing. One book, suitable for a particular age group, is chosen for further reflection. Of the books mentioned, I really admired Absolution by Alice McDermott, and reviewed in in my blog of July 5, 2023.

About the Author

Michelle Herman is the author of the novels Missing, Dog, Devotion, and Close-Up and the collection of novellas A New and Glorious Life, as well as four essay collections—The Middle of Everything, Stories We Tell Ourselves, Like A Song, and If You Say So—and a book for children, A Girl’s Guide to Life. She writes a popular family and relationship advice column for Slate, and for many years she taught creative writing at Ohio State, in the MFA program she was a founder of in the early nineties. More about the author .

American Politics

August 20, 2025

Heather Cox Richardson from Letters from an American <heathercoxrichardson@substack.com>

President Donald J. Trump created a firestorm yesterday when he said that the Smithsonian Institution, the world’s largest museum, education, and research complex, located mostly in Washington, D.C., focuses too much on “how bad slavery was.” But his objection to recognizing the horrors of human enslavement is not simply white supremacy. It is the logical outcome of the political ideology that created MAGA. It is the same ideology that leads him and his loyalists to try to rig the nation’s voting system to create a one-party state.

That ideology took shape in the years immediately after the Civil War, when Black men and poor white men in the South voted for leaders who promised to rebuild their shattered region, provide schools and hospitals (as well as desperately needed prosthetics for veterans), and develop the economy with railroads to provide an equal opportunity for all men to work hard and rise.

Former Confederates, committed to the idea of both their racial superiority and their right to control the government, loathed the idea of Black men voting. But their opposition to Black voting on racial grounds ran headlong into the Fifteenth Amendment to the Constitution, which, after it was ratified in 1870, gave the U.S. government the power to make sure that no state denied any man the right to vote “on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” When white former Confederates nonetheless tried to force their Black neighbors from the polls, Congress in 1870 created the Department of Justice, which began to prosecute the Ku Klux Klan members who had been terrorizing the South.

With racial discrimination now a federal offense, elite white southerners changed their approach. They insisted that they objected to Black voting not on racial grounds, but because Black men were voting for programs that redistributed wealth from hardworking white people to Black people, since hospitals and roads would cost tax dollars and white people were the only ones with taxable property in the Reconstruction South. Poor Black voters were instituting, one popular magazine wrote, “Socialism in South Carolina.”In contrast to what they insisted was the federal government’s turn toward socialism, former Confederates celebrated the American cowboys who were moving cattle from Texas to railheads first in Missouri and then northward across the plains, mythologizing them as true Americans. Although the American West depended on the federal government more than any other region of the country, southern Democrats claimed the cowboy wanted nothing but for the government to leave him alone so he could earn prosperity through his own hard work with other men in a land where they dominated Indigenous Americans, Mexicans, and women.

That image faded during the Great Depression and World War II as southerners turned with relief to federal aid and investment. Like them, the vast majority of Americans—Democrats, Independents, and Republicans—turned to the federal government to regulate business, provide a basic social safety net, promote infrastructure, and support a rules-based international order. This way of thinking became known as the “liberal consensus.”

But some businessmen, furious at the idea of regulation and taxes, set out to destroy the liberal consensus that they believed stopped them from accumulating as much money as they deserved. They made little headway until the Supreme Court in 1954 unanimously decided that segregation in public schools was unconstitutional. Three years later, Republican president Dwight D. Eisenhower federalized the Arkansas National Guard and mobilized the 101st Airborne Division to protect the Black students at Little Rock Central High School. The use of tax dollars to protect Black rights gave those determined to destroy the liberal consensus an opening to reach back and rally supporters with the racism of Reconstruction.

Federal protection of equal rights was a form of socialism, they insisted, and just as their predecessors had done in the 1870s, they turned to the image of the cowboy as the true American. When Arizona senator Barry Goldwater, who boasted of his western roots and wore a white cowboy hat, won the Republican nomination for president in 1964, convention organizers chose to make sure that it was the delegation from South Carolina—the heart of the Confederacy—that put his candidacy over the top.

The 1965 Voting Rights Act protected Black and Brown voting, giving the political parties the choice of courting either those voters or their reactionary opponents. President Richard Nixon cast the die for the Republicans when he chose to court the same southern white supremacists that backed Goldwater to give him the win in 1968.As his popularity slid because of U.S. involvement in Vietnam and Cambodia and the May 1970 Kent State shooting, Nixon began to demonize “women’s libbers” as well as Black Americans and people of color. With his determination to roll back the New Deal, Ronald Reagan doubled down on the idea that racial minorities and women were turning the U.S. into a socialist country: his “welfare queen” was a Black woman who lived large by scamming government services.After 1980, women and racial minorities voted for Democrats over Republicans, and as they did so, talk radio and, later, personalities on the Fox News Channel hammered on the idea that these voters were ushering socialism into the United States. After the Democrats passed the 1993 National Voter Registration Act, often called the “Motor Voter Act,” to make registering to vote in federal elections easier, Republicans began to insist that Democrats could win elections only through voter fraud.

Increasingly, Republicans treated Democratic victories as illegitimate and worked to prevent them. In 2000, Republican operatives rioted to shut down a recount in Florida that might have given Democrat Al Gore the presidency. Then, when voters elected Democratic president Barack Obama in 2008, Republican operatives launched Operation REDMAP—Republican Redistricting Majority Project—to take control of statehouses before the 2010 census and gerrymander states to keep control of the House of Representatives and prevent the Democrats from passing legislation.

In that same year, the Republican-dominated Supreme Court reversed a century of campaign finance restrictions to permit corporations and other groups from outside the electoral region to spend unlimited money on elections. Three years after the Citizens United decision, the Supreme Court gutted the Voting Rights Act that protected minority voting.

Despite the Republican thumb on the scale of American elections by the time he ran in 2016, Trump made his political career on the idea that Democrats were trying to cheat him of victory. Before the 2016 election, Trump’s associate Roger Stone launched a “Stop the Steal” website asking for donations of $10,000 because, he said, “If this election is close, THEY WILL STEAL IT.” “Donald Trump thinks Hillary Clinton and the Democrats are going to steal the next election,” the website said. A federal judge had to bar Stone and his Stop the Steal colleagues from intimidating voters at the polls in what they claimed was their search for election fraud.

In 2020, of course, Trump turned that rhetoric into a weapon designed to overturn the results of a presidential election. Just today, newly unredacted filings in the lawsuit Smartmatic brought against Fox News included text messages showing that Fox News Channel personalities knew the election wasn’t stolen. But Jesse Watters mused to Greg Gutfield, “Think about how incredible our ratings would be if Fox went ALL in on STOP THE STEAL.” Jeanine Pirro, now the U.S. attorney for the District of Columbia, boasted of how hard she was working for Trump and the Republicans.

In forty years, Republicans went from opposing Democrats’ policies, to insisting that Democrats were socialists who had no right to govern, to the idea that Republicans have a right to rig the system to keep voters from being able to elect Democrats to office. Now they appear to have gone to the next logical step: that democracy itself must be destroyed to create permanent Republican rule in order to make sure the government cannot be used for the government programs Americans want.

Trump is working to erase women and minorities from the public sphere while openly calling for a system that makes it impossible for voters to elect his opponents. The new Texas maps show how these two plans work together: people of color make up 60% of the population of Texas, but the new maps would put white voters in charge of at least 26 of the state’s 38 districts. According to Texas state representative Vince Perez, it will take about 445,000 white residents to secure a member of Congress, but about 1.4 million Latino residents or 2 million Black residents to elect one.In order to put those maps in place, the Republican Texas House speaker has assigned state troopers to police the Democratic members to make sure they show up and give the Republicans enough lawmakers present to conduct business. Today that police custody translated to Texas representative Nicole Collier being threatened with felony charges for talking on the phone, from a bathroom, to Democratic National Committee chair Ken Martin, Senator Cory Booker (D-NJ), and Democratic California governor Gavin Newsom.

Republicans have taken away the liberty, and now the voice, of a Black woman elected by voters to represent them in the government. This is a crisis far bigger than Texas.

When Trump says that our history focuses too much on how bad slavery was, he is not simply downplaying the realities of human enslavement: he is advocating a world in which Black people, people of color, poor people, and women should let elite white men lead, and be grateful for that paternalism. It is the same argument elite enslavers made before the Civil War to defend their destruction of the idea of democracy to create an oligarchy. When Trump urges Republicans to slash voting rights to stop socialism and keep him in power, he makes the same argument former Confederates made after the war to keep those who would use the government for the public good from voting.Led by Donald Trump, MAGA Republicans are trying to take the country back to the past, rewriting history by imposing the ideology of the Confederacy on the United States of America.

But that effort depends on Republicans buying into the idea that only women and minorities want government programs. That narrative is falling apart as cuts to the government slash programs on which all Americans depend and older white Americans take to the streets. Today, with the chants of those protesting Trump’s takeover of Washington, D.C., echoing in the background, White House deputy chief of staff Stephen Miller told reporters: “We’re not going to let the communists destroy a great American city…. [T]hese stupid white hippies…all need to go home and take a nap because they’re all over 90 years old, and we’re gonna get back to the business of protecting the American people and the citizens of Washington, D.C.”—

Notes:https://www.nytimes.com/2025/08/19/us/politics/trump-smithsonian-slavery.htmlhttps://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/citizens-united-explainedhttps://www.cnn.com/2020/11/13/business/stop-the-steal-disinformation-campaign-invs“Socialism in South Carolina,” The Nation, April 16, 1874, pp. 247–248.https://www.newsweek.com/fox-news-hosts-private-texts-revealed-lawsuit-bombshells-2116299https://time.com/7310875/texass-map-racial-division/https://www.politico.com/story/2016/11/ohio-injunction-trump-roger-stone-polls-230754Bluesky:thejenniwren.teamlh.social/post/3lwuaavezhc2uatrupar.com/post/3lwtvjaw3vq2a

Alternet *

*This site is a source of optimistic insight into the Democratic Party’s responses to President Trump, so much so, that I usually do not use it here – just enjoy the maybe misplaced optimism. However, there is some valuable material for reflection in this article.

MAGA is panicking as Trump finally meets his match | Opinion

Opinion by Thom Hartmann

The effect is unmistakable: the California governor is shifting the cultural battlefield, showing that Democrats can seize the same terrain of humor and symbolism Republicans have dominated since Richard Nixon’s “law and order” days. Newsom has left conservative pundits — particularly on Fox “News” — sputtering.

It’s the kind of cultural jujitsu that Antonio Gramsci imagined — flipping power by seizing the symbols and frames of your opponent — and it’s the kind of thing Democrats have needed to do for years but haven’t successfully pulled off since the days of FDR’s New Deal and LBJ’s Great Society.

To truly rule with the broad consent of a nation’s citizens, he realized, you have to shape the culture. You have to convince people that your worldview is “common sense,” that your version of reality is the only normal, natural way to see the world.

He called this “cultural hegemony.” The churches, the schools, the newspapers, the songs people sang, the plays they watched and the stories they told all carried values. And those values shaped politics far more than any speech in parliament.

If you win the cultural battle, he argued, you will inevitably win the political one.

Their solution was simple: steal Gramsci’s insight and use it to push back. Andrew Breitbart put the slogan on bumper stickers: “Politics is downstream from culture.” Steve Bannon made it into a strategy for the Trump White House.

Change the story the nation tells itself, control the cultural conversation, and politics will follow.

Republicans have taken that playbook and used it ruthlessly. Following Frank Luntz and other experts’ advice, they reduce every issue to a frame that touches the gut, not the head, and then repeat it until it becomes the background noise of American life.

Nixon gave us one of the earliest, ugliest examples. His “law and order” campaign wasn’t about crime in general; it was code for crushing the civil rights movement and suppressing Black political power.

His “war on drugs” wasn’t a moral crusade against addiction; as his aide John Ehrlichman later admitted, it was a way to criminalize Black people and anti-war activists. They couldn’t outlaw being Black or protesting the Vietnam War, but they could associate both with drugs and then use police and prisons to break movements and communities.

That was cultural framing at its most cynical and vicious. Nixon didn’t have to talk about race. He just had to say “law and order” and “drugs,” and racist white voters understood the code.

The pattern has repeated itself ever since.

When Republicans attack reproductive rights, they don’t say they want to outlaw abortion or strip women of autonomy; they say they’re defending “life.” That single word is a cultural sledgehammer. Democrats, for years, answered with “choice,” which at least carried some emotional punch, but over time they got pulled into defending Planned Parenthood against smears and explaining the economic dimensions of reproductive healthcare as a women’s “economic issue.” Important arguments, yes, but they don’t resonate at the same visceral level as “life.”

On healthcare, Republicans took the word “choice” and made it their own. “Choose your own doctor” became the mantra of those defending corporate-controlled healthcare and insurance. Democrats talked about “single payer” or “public options,” language that could have come out of an actuary’s report. “Choice” sounds American, even when it means choosing between bad insurance plans or facing bankruptcy.

When Republicans use Reagan’s favorite phrase “small government,” people picture a plucky individual freed from bureaucrats and taxes, a man out west on horseback making a life for himself and his family out of the wilderness. What they mean, though, is making government too weak to tax billionaires, regulate corporate pollution, or protect people from discrimination.

But Democrats never met this frame with one of their own. Instead of talking about “government that works for all,” as FDR and LBJ once did, Democrats let the conversation drift into debates over the Affordable Care Act’s exchanges or the technical structure of regulatory agencies.

FDR understood that people don’t want less government or more government; they want a government that works for them. That is a cultural message, not a policy paper, and Democrats have abandoned it ever since Jimmy Carter’s well-intentioned but wonk-driven presidency.

Republicans say “tax relief,” and suddenly taxes are a disease from which you need to be liberated. Democrats counter with discussions about marginal rates and progressive brackets instead of using FDR’s old line that, “Taxes are what we pay for civilized society. Too many individuals, however, want civilization at a discount.”

Republicans say “red tape,” and instantly every rule protecting you from being poisoned, cheated, or injured is recast as a useless nuisance. Democrats instead talk about the importance of “regulation,” something all of us would like less of in our lives.

Republicans say “freedom,” and people see flags and hear the national anthem. Instead Democrats, too often, talk about “programs” or “safety nets.”

The same dynamic plays out on guns. Republicans wrap the issue in the word “freedom” and the power to “fight tyranny.” Democrats come back with talk about universal background checks and assault weapons bans. Important, necessary measures, but they don’t touch the same cultural nerve.

Democrats could have framed gun control differently: freedom from being shot at school, freedom from being afraid in a grocery store, freedom from the constant terror that your child might not come home. That’s freedom that resonates with ordinary people. But by ceding the cultural word “freedom” to the GOP, Democrats let Republicans define what freedom means in America.

On immigration, Republicans talk about “secure borders” and “sovereignty.” Democrats talk about “pathways to citizenship.” Republicans make it about the survival of the nation, Democrats make it about paperwork. The Democratic Party is the party of the Statue of Liberty (that was installed during Democrat Grover Cleveland’s presidency), yet Republicans have stolen the cultural image of America and turned it into one of a fortress under siege.

Education has become another cultural battlefield. Republicans push “parents’ rights” and book bans “to protect our children.” Democrats respond with statistics about test scores and defenses of teachers’ unions. But the cultural high ground belongs to the idea that every child has the right to learn the truth, and every parent has the right to send their kid to school without censorship or fear. Republicans frame themselves as liberators of children, even as they chain them to ignorance. Democrats need to call that out for what it is, in cultural terms that are impossible to ignore.

The lesson is the same in every case. Republicans don’t win by having better policies: their policies are almost uniformly cruel, corrupt, and designed to serve the morbidly rich at the expense of everyone else. They win because they fight at the cultural level. They win because they tell a story, over and over, that makes people feel. Democrats, for decades, have responded with charts that only tickle the intellect.

It wasn’t always this way. During the New Deal and the Great Society, Democrats owned the culture wars. FDR didn’t talk about the Securities and Exchange Commission; he talked about “saving capitalism from itself,” about “restoring faith in America,” about “freedom from want and fear.”

Lyndon Johnson didn’t just present Medicare as a program; he said it was part of building a Great Society where people could live with dignity. He sold the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts with similar rhetoric. Those were cultural narratives, not policy briefs. They tied the Democratic party to the most powerful emotions and aspirations of the American people.

If Democrats want to win again, they have to stop ceding the cultural battlefield. Instead, they need to seize today’s opportunities to fully engage in the culture wars, from policy prescriptions to Gavin Newsom ridiculing Trump to JB Pritzker calling out the GOP’s embrace of fascism.

That means reframing every major issue not just in terms of policy mechanics, but in terms of the classic and compelling American values of freedom, fairness, safety, dignity, and opportunity.

Taxes aren’t a burden; they are the way we all pay for the freedom and opportunity America makes possible.

Regulations aren’t red tape; they are the rules that keep the game fair.

Healthcare isn’t about exchanges; it’s about whether you have the right to live without fear of medical bankruptcy.

Guns aren’t about background checks; they’re about whether your child comes home from school alive.

Immigration isn’t about paperwork; it’s about whether America still stands for the promise on the Statue of Liberty.

Republicans learned from Gramsci and weaponized culture. They turned it into dog whistles, slogans, and memes that bypass reason and lodge themselves in the national gut. Democrats can learn from the same source without resorting to the GOP’s lying, cruelty, and thinly coded racism.

The closest Democrats have come in recent years was Barack Obama’s “Hope and Change” campaign in 2008, revisited in 2012. But those terms, while culturally potent, lost their impact as the Democratic Party continued to bow to the demands of the banks (not a single bankster went to prison for the 2008 crash they caused) and health insurance (Obamacare was written by the Heritage Foundation and gifted the industry with trillions after Obama dropped the public option) industries.

We can tell the story of freedom that is big enough to include everyone. We can tell the story of America not as a fortress for billionaires but as a community where everyone has a fair shot and nobody is left behind.

Like FDR and LBJ, Democrats can again talk about America realizing its potential as a “we society” instead of the selfish Ayn Rand “me society” that Republicans idolize with their “I got mine, screw the middle class” policies and memes.

The alternative is to keep losing ground to a Republican Party that has mastered the art of cultural hegemony in the worst sense of the term. Nixon showed how destructive that could be with his law and order rhetoric. Reagan perfected it with his “welfare queen” lies. Trump and Bannon have pushed it into the realm of authoritarian spectacle, where politics becomes theater and culture becomes a weapon to bludgeon democracy itself.

It doesn’t have to be this way.

The Democrats of the New Deal and Great Society eras knew how to speak to the heart as well as the head. They knew that politics is not just about what laws are passed but about what stories a nation tells itself about who it is. They knew that culture is not an afterthought; it is the riverbed through which politics flows.

Republicans now know it too, and they’ve been poisoning that river for half a century. If Democrats want to save democracy, they must reclaim the story of America, the cultural high ground, and the word freedom itself.

The joy of the quiet time of year

Dervla McTiernan

View this email in your browser  Was this email forwarded to you? Am I in your inbox for the first time? I’d love it if you sign up to my newsletter here. Friday, 22 August 2025 [slightly edited].

Was this email forwarded to you? Am I in your inbox for the first time? I’d love it if you sign up to my newsletter here. Friday, 22 August 2025 [slightly edited].

Hello Robin,

I’m happy to tell you that I’m in that quiet period of the year. The thing about traditional publishing is that it works on a cycle. For the two months before and the two months after your book comes out you are generally caught up in the whirl of promotional work. There are writers, I think, who do less promotion, and certainly there are many writers who do more, but these days it would be difficult to find a writer who doesn’t do any.

The reality is that we live in a very noisy, busy world, and it’s so easy for a book even by your favourite writer to pass you by (case in point — I completely missed the existence of a Sophie Hannah book that I just came across on Audible and I LOVE her work!).

So promotion is now very much part of my life, and I like it, really. It’s fun to do something so completely different, and a joy to go out on the road and to meet so many people and talk books. Also … sometimes it is all so totally worth it. I was in Dymocks the other day and spotted The Unquiet Grave still in the top ten, and it’s been out for months and months! So thank you to everyone who is reading. I’m eternally grateful.

After the main hubbub of launch is over, writers go into the quiet time of year. This year, I focused first on getting my structural edit done, and as that’s now off my desk I’m mainly spending my time on family bits and pieces, and working my way slowly through the list of jobs I put off during busier times. One particular job is turning out to be something exciting. I’m having my website redesigned and it’s one of those rare situations where you ask someone to do something and you have very high hopes and then they just deliver and deliver and deliver! The whole design is so rich and gorgeous and it feels like being on the website is like being in the world of the books. (

QUESTION??A question for you! I’m putting lots of new material on the website. In terms of downloadable content, is there anything in particular you’d like to have? The only thing I can really think of that you might like to have off the website is questions and notes for book clubs. If anything else occurs to me, please do email me and let me know.

I sent my new book off to my editors a few weeks ago so it is very close to being finished now. I’ll get notes back from my editors at the end of the month, and then I’ll have just over three weeks to turn it around and get it back to them. And you know what? At that stage I’ll already have had a planning meeting with my publisher for the launch of that book next year! I’m not sure I’m ready for that …

The main project I’m working on right now is my new new book (not the one that will be out next year, but the one after that). I’m starting a new series (don’t tell anyone, that’s a secret). I’ve been planning this for ages, which is such a good thing, because before I’ve even gotten into the writing of it, the world has become so rich and exciting to me. The story and the characters already feel real, and the longer I’ve been held back from writing it by other projects, the more I want to write it, which is such a good sign.

By the time I email you next I should have almost finished my copy edit and I’ll be well into the new book. Wish me luck!

I went to Byron Writers Festival this month and had a grand old time, which I feel pretty guilty about, because most of the festival had to be cancelled because the rain was so intense. I was just lucky that my workshop and panel event were right at the beginning, because by the time I was leaving on Friday we were well and truly flooded, and more rain was on the way.

My panel event was with Michael Robotham and Chris Hammer and our moderator was Marele Day. We had such a lovely warm welcoming audience, and Michael and Chris were both hilarious, which made for a memorable event! (iykyk!)

I also taught a workshop on writing, which is something I do very rarely, and I’m not sure I’m in a rush to do again. It was a very fun morning, and a privilege to meet the lovely writers who attended, and I really do love talking all things writing, but with time so tight these days, I want to give all the time I have to writing, as opposed to preparing for or attending events and workshops. The thing about being a writer is that there’s always another distraction waiting around the corner and you can always convince yourself that it’s work but at the end of the day it all draws you away from the real thing!

Thanks so much to everyone who emailed me about The Correspondent. A lot of people seem to have read it and all of the comments were very positive. I thoroughly enjoyed it. It was a very compelling story, and it was so rewarding to spend time with a writer who so deeply understands the topic they’re writing about, who can give real information and nuanced point of view about something so complex. Another reminder of the joy of books and a relief to get away from the constant outrage bait and hot takes on social media!

For this month, I’m going to read one of my favourite writers. If you’ve ever attended one of my events, you’ll have heard me talk about Tana French. She’s an Irish writer and her books are generally described as literary crime. I want to go right back to her debut novel, In The Woods, to see if it has the same effect on me today that it did when it came out. I remember it being completely compelling, that I just had to turn the pages. I remember the shock of the twist, and how real the characters felt to me. So! If you’d like to join me, you can order the book online or from all good bookshops. If you do read it, please do let me know what you think!

All my best,

Dervla.

Copyright © 2025 Dervla McTiernan, All rights reserved.

You are receiving this email because you opted in via dervlamctiernan.com

Our mailing address is:

Dervla McTiernanC/o- Jin & Co. 1/506 Neerim

Women and Literature

Barbara Pym, The Sweet Dove Died

Barbara Pym’s social comedies are pure post-war delights. The English writer close read middle-class village life in her tightly constructed novels of manners, and reclaimed “spinsterhood” for glorious loners everywhere.

Her arguable masterpiece follows the vain Leonora Eyre over and around a fraught love quadrangle with a widowed antiques dealer, his nephew, and some other motley souls. The NYRB Classics crew has selected this book for its October club on the strength of what The Guardian once called “faultless” prose.

The Reality behind Barbara Pym’s Excellent Women: The Troublesome Woman Revealed (excerpt)

Spinsterhood is an important theme in Barbara Pym novels and short stories, one that I was keen to develop in my book.:

The surfeit of unmarried women who people Pym’s fiction provides a wealth of variety in what a spinster might be, or how she might act. Many are given central roles in Pym’s novels. Their depiction, as described throughout the texts, is dealt with in detail in Chapter 2. They highlight qualities that undermine, rather than reinforce, the traditional, non-feminist view of a spinster. Under Pym’s guidance, the term spinster becomes the personification of a strong, individualistic woman, a feminist interpretation of what a spinster can be, when given a central role. However, Pym also gives spinsters secondary, or fleeting roles, in her fiction. However fleeting or modest the role, the stereotype is usually toppled, or if portrayed as what has been designated a typical spinster, is developed with accoutrements, jarring qualities that enforce a reassessment of how a spinster should behave. Pym develops these inconsistencies with a sharpness that shows her enthusiasm for undermining the spinster stereotype.

Central spinsters are Jessie Morrow who, amongst her several appearances, features with Miss Doggett and Barbara Bird in Crampton Hodnet, Catherine Oliphant, Esther Clovis and Deidre Swan in Less Than Angels, Mary Beamish in A Glass of Blessings, Dulcie Mainwaring and Viola Dace in No Fond Return of Love, Ianthe Broome in An Unsuitable Attachment, Leonora Eyre in The Sweet Dove Died, Marcia Ivory and Letty Crowe in Quartet in Autumn and Emma Howick in A Few Green Leaves. They are a vital part of the community in these works and are represented in a variety of relationships and with a range of behaviours and lifestyles.

Where depictions of spinsters are brief, they nonetheless demonstrate Pym’s continuing and sustained interest in portraying single women as individuals rather than members of a stereotypical group. Spinsters appear briefly in Crampton Hodnet, Less Than Angels, A Glass of Blessings, No Fond Return of Love and The Sweet Dove Died, and in greater depth in A Few Green Leaves. Crampton Hodnet includes young spinsters, one about to go to Oxford, and involved in flirtations which are momentarily disappointing; a young woman who contributes to that disappointment; a potential first-class honours student about to embark on an affair with her tutor, and her university friends; a young woman who ‘had an unpleasant experience in Paris’ (CH, 151) and a potential fiancé. Another companion is mentioned and there are additional single working women, such as maids, a nun, three Oxford college tutors and a college Principal. There are two ‘dim North Oxford spinsters’ (CH, 29) in new hats, one of whom elicits possible censure with her newly waved hair; ‘groups of North Oxford spinsters at tea after shopping’ (CH, 52) and spinsters amongst a church congregation.

Spinsters who feature in Jane and Prudence continue Pym’s pattern of providing single women with a variety of characteristics and lifestyles. Flora, Jane’s daughter will be studying at Oxford, but in the meantime displays the domesticity that her mother spurns, yearns after various men briefly and is practical in the face of her mother’s fanciful imaginings and behaviour. Miss Jellink, the Principal and Miss Birkenshaw, head of English at Oxford, are unmarried professionals. Miss Clothier and Miss Trapnell are office workers of indeterminate age and occupation. Their concern about working only the requisite hours is contrasted with the young typists who display no interest in time keeping and talk casually of their elders (JP, 109-110). Miss Bird, a friend of Jane Cleveland’s, makes a brief appearance as a writer who seizes a plate of sandwiches to eat by herself at a literary function (JP, 131-132).

Less Than Angels includes spinster anthropologists, one of Bolshevist views and the other a flirt, who compete for funding to go into the field; ‘an expert in African languages’ (LTA, 8-9); an aunt who combines a vivid imagination, observance of ritual and resentment against a clergyman; a spinster aunt deemed, by her unmarried state, inferior to her married sister (LTA, 29); two fiancés and a rejected lover who is also a breeder of golden retrievers; ‘a tweedy little woman of a mild, almost downtrodden aspect’ (LTA, 153) is Miss Jessop, who also features in Excellent Women; a tall debutante with a desperate mother; a mistaken identity which links stereotypical understandings about spinsters with one who is not a stereotype; and mention of young women who ‘Either said nothing “submitted to his embraces” […] or pushed him away indignantly’ (LTA, 26) or as members of the local club ‘might also be considered amongst its amenities […but] often led [men] captive in marriage’ (LTA, 37).

A Glass of Blessings includes typists and a young woman who works in a coffee shop. The warden of the Settlement is a spinster; other spinsters are a former governess on familiar terms with people of a higher status after her retirement; nuns; ‘two elderly spinsters [learning Portuguese] who plan to hitchhike around Portugal and write a book about it’(AGB, 64); two young attractive spinsters who are learning Portuguese for ‘personal and romantic reasons’ (AGB); and another whose reason for learning Portuguese is unclear; a spinster with a unique blood type who demands special treatment at the blood donor clinic; women in the civil service including one in a principal role in the ministry; ‘splendid Miss Hitchens’ (AGB, 132) and her friend Prudence Bates, a central character in Jane and Prudence; spinsters who are the source of conversation with feminist overtones (AGB); a worker with galley proofs; and unmarried mothers.

The third spinster who appears in No Fond Return of Love is ‘a fellow lecturer’ (NFRL, 9) to the key male character in the novel and the next is the ‘librarian of quite a well-known learned institution’ (NFRL, 13). Variety and commentary on women’s work are added by the introduction of a spinster who prefers housework ‘which nowadays did not seem to be regarded as in any way degrading’ (NFRL, 29); another working in a haberdashery department; the main character’s niece who arrives to work in London after leaving school; a science lecturer at London University; a helpful woman, Rhoda Wellcome, from Less Than Angels, at a jumble sale; an elderly aunt whose previous work in censorship is followed by parish and committee work, and at the end of the novel is said to be marrying a vicar; another woman about to marry, but who has been a headmistress; a young woman who expects that women will be in the workforce; and, more typically, a spinster who minds her elderly mother and is distressed about a handsome clergyman.

The Sweet Dove Died focuses on Leonora, a spinster in her fifties, and introduces few characters who do not belong explicitly to her world. Even in this limited sphere there are spinsters of varying personalities and occupations. Leonora’s spinster friend from their working days is infatuated with a young gay man; and her tenant is an elderly spinster. On the periphery of her life, but a threat to her friendship with a young man, is a spinster who is a sexually free writer; an uncompetitive, admiring middle-aged spinster who works with the young man at the antique shop; and the spinster, so recognised because her basket holds a dinner for one, for whom Pym provides alternative views of spinsterhood: a woman alone and pitiful, or a woman ‘going home to cosy solitude’ (TSDD,140-141).

In An Unsuitable Attachment, the additional spinsters featured are the vicar’s wife’s sister, a secretary to a London publisher; a retired hospital nurse; the vet’s sister who assists him in the surgery; a retiring library assistant; a dressmaker; nuns; and two seventy-year-old English spinsters holidaying in Rome, the Misses Bede from Some Tame Gazelle. The spinsters in An Academic Question are a Swedish au pair; a young lecturer who would prefer to eat than talk to her male companion; the owner of a second hand bookshop with ‘a preoccupation with animals and interest in the problems of loneliness, […and a] sardonic attitude towards academics’ (AAQ, 15); a university student; a nursing home matron; the unmarried sister of the central character; a former principal of a teachers’ college; an assistant editor on a sociology journal; and a lover of medical romances. The novel includes a reference to the well-known Pym spinster character from Less Than Angels, Miss Clovis, whose funeral is attended by the main character.

Quartet in Autumn, which gives two markedly different spinsters central roles, also features ‘a young black girl, provocative, cheeky and bursting with health,’ (QA, 8) who works in the same office as the main characters; a single landlady and two spinster tenants; and a retirement home resident warden.

As Pym moved into her new phase of writing, the number of spinsters peripheral to the main theme diminished. The work from the 1960s, with its stronger undertones and eventually openly feminist ideas needs fewer outwardly comforting characters. Although they are troublesome women and carried Pym’s feminist narrative, spinsters also provided an aspect of her village cover. As previously noted, in the later novels, that function was no longer necessary.

However, with her novel that sets aside the village image, almost going for the jugular of village cosiness, A Few Green Leaves, Pym returns to her practice of including multiple characters who feature more than fleetingly, while not necessarily being central. They include a range of spinsters. Some spinsters who appear briefly in A Few Green Leaves are ageing and might be expected to fall easily into stereotypical positions. The novel gives troublesome roles to the rector’s sister in her fifties and in love with Greece; ‘a long-established village resident’ (AFGL, 8); a spinster ‘of uncertain age’ (AFGL, 11) who has written a romantic historical novel; ‘a small, bent woman in an ancient smelly coat’ (AFGL, 18) who encourages hedgehogs into her house; a former governess; a librarian; young women in church or the local pub; a former headmistress; ‘Tom’s history ladies’ (AFGL, 100), a group that is likely to include spinsters; a worker in a museum; a student ‘recovering from an unsatisfactory love affair and writing a novel’ (AFGL, 210) and reference to Miss Clovis’ death as ‘the passing of a formidable female power in the anthropological world’ (AFGL, 133).

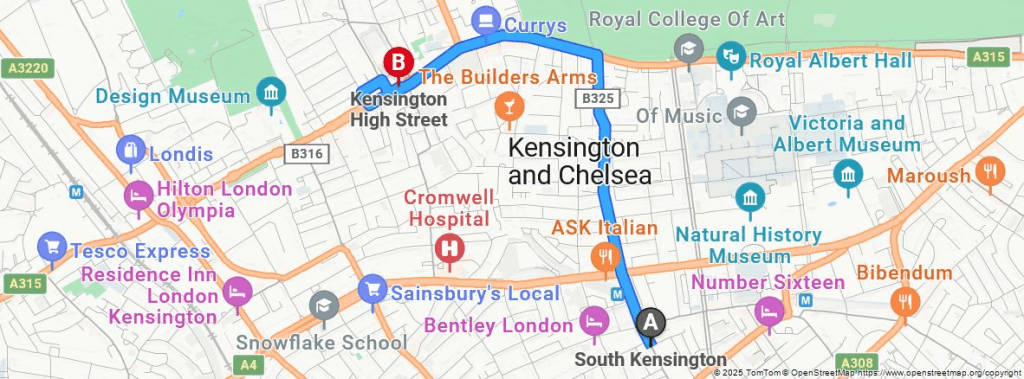

Secret London

This Tiny London Street Is Known As ‘Little Paris’ Filled With French Bakeries, Old Bookshops And Even A Vintage Cinema – And You Probably Don’t Know It

Vaishnavi Pandey – Staff Writer • 16 August, 2025

Everything about this corner feels less like London and more like the 5th arrondissement: independent bakeries with baguettes stacked behind the glass.

London is full of secrets – hidden mews, tucked-away gardens, and short streets that feel like stepping through a doorway into another city. Yet, just a few minutes from South Kensington’s high street, there is a quiet lane where the air smells of fresh croissants, where conversations often switch effortlessly into French, and where old volumes of Camus, Balzac, and Colette spill from bookshop shelves.

Everything about this corner feels less like London and more like the 5th arrondissement: independent bakeries with baguettes stacked behind the glass, cafés where regulars greet each other with a warm bonjour, and cultural sanctuaries devoted to French literature and film.