Elizabeth Strout Tell Me Everything Penguin General UK (Fig Tree, Hamish Hamilton, Viking, Penguin Life, Penguin Business, Viking) September 2024.

Thank you, NetGalley, for providing me with this uncorrected proof for review.

Elizabeth Strout brings magic to her work and Tell Me Everything is no different. Bob Burgess and Margaret Estaver live in Maine. The enchantment of Maine’s autumn colours interspersed with prosaic and sometimes graphic detail is the setting for their marriage, their large house in which they cook together, and the security this couple, a lawyer and a Unitarian minister, provide the community. Olive Kitterage, ninety, knows the couple, sympathises with Bob’s sad past, is not fond of Margaret and has suffered through the pandemic. Lucy Barton, also from previous novels, is an important character, although mostly inconspicuous in the larger community apart for walking with Bob along the river. As autumn breaks into splendour, Olive decides to tell her story to Lucy.

Here Lucy Barton becomes a character whose relationship with Bob Burgess and Margaret Estaver meanders through the story told by Olive Kitterage. There is delicious detail in their meetings, from their surrounds, appearance and the stories that are shared through their relationship. Love is the overwhelming theme, and aspects of love permeate the conversations and interactions. At the same time as Olive Kitterage tells her story to Lucy Barton, each is observing and understanding more about the relationships around them. Bob Burgess and Margaret Estaver are also thinking about their understandings of love.

Elizabeth Strout has such an alive way of writing. Lively is not the right word, that her narrative is alive, so alive, immediate and fascinating is the overwhelming feeling I have from reading her work. I read her novels for that as well as the stories she weaves that concurrently engage, compel and dance away from any prosaic understanding. Strout’s work is a joy to read, and I always look forward to enjoining with her conversations on the page.

Jane Loeb Rubin In the Hands of Women Level Best Books, Independent Book publishers Association (IBPA), Members’ Titles, May 2023.

Thank you, NetGalley, for providing me with this uncorrected proof for review.

In the Hands of Women is set in New York in the early 1900s, with Hannah Isaacson, a MD in obstetrics as the central character. Not only does she suffer from discrimination against women, but antisemitism. Her public life is centred around the hospital in which she works, the prison in which she is wrongly incarcerated and her activism on behalf of women. Hannah Isaacson also has a private life in which the sexist nature of women and men’s relationships is depicted through her friendships with women and relationships with men. Her family life is also an important feature of the novel, driving an even greater understanding of the medical practices Isaacson sought to improve in relation to childbirth. Abortion, and the laws surrounding it, as well as the personal impact of abortion make graphic reading.

Hannah and her family are engaging characters, strong, supportive and warm. They are fictional, but one has her genesis in a family member. Other characters are taken from real life – John Hopkins Trustees, Mrs Garret and Mrs Thompson; New York State governors, Higgins and Hughes; and Margaret Sanger, an advocate for women. Loeb Rubin attests that the political climate and medical situation that she depicts have their basis in fact. She has researched widely, referring to the non-fiction material and research staff of museums and libraries that assisted her at the end of the novel in a bibliography and acknowledgements. See Books: Reviews for the complete review.

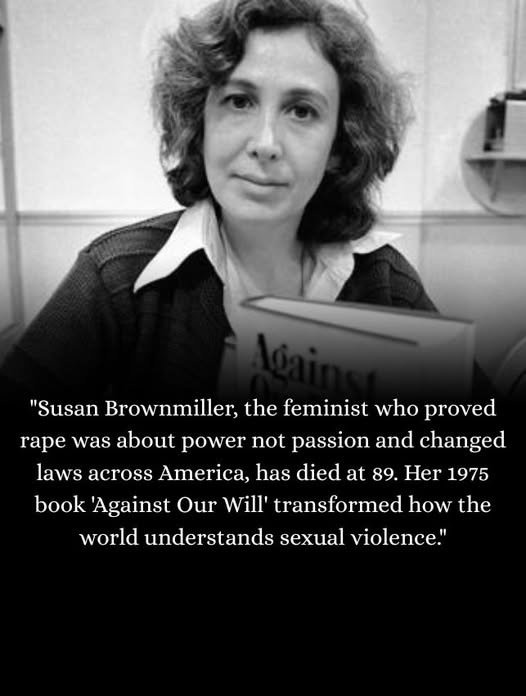

Books & the Arts / February 6, 2026

Barbara Pym’s Archaic England

In the novelist’s work, she mocks English culture’s nostalgia, revealing what lies beneath the country’s obsession with its heritage.

Within a year after Barbara Pym published her penultimate novel, The Sweet Dove Died, Margaret Thatcher would assume office as prime minister of the United Kingdom. In retrospect, these two events seem not unrelated. The 1978 novel marks a shift in the British writer’s career; published shortly after her return to print after a 15-year hiatus, The Sweet Dove Died ditches the comic tone of Pym’s earlier work for a set of themes that dominated her final novels: nostalgia, festering traditionalism, the feeling of outmodedness—concerns, in other words, gathered from her measured observation of a society on whose discontents Thatcher would soon capitalize.

Thatcher rose to power on the back of a campaign to Make Britain Great Again—a promise to reverse the previous two decades of austerity, imperial contraction, and stagnating modernization. By 1979, the country was undeniably in decline—not just materially but on a more ineffable level, too. Divested of the unifying effect of global superpower status, the increasingly dis-United Kingdom’s common identity was now an open, and anxious, question. What would ensure the shared future of the nation? For Thatcher and her ilk, the answer (at least rhetorically) lay in conjuring an ideal imperial past and the fantasies of Merrie England that went with it: the Crown, the Empire, green pastures and trout runs, the 12th of August, upstairs and downstairs, overseas plantations, and Gloucester cheese. With one hand, Thatcher’s government rolled out staunchly anti-traditional monetarist policies; with the other, it stoked a reactionary fantasy of once and future greatness. If Thatcher’s neoliberal solutions—privatization, deregulation, reduced public spending—helped spur a modest economic recovery, their more memorable consequence was to gut the social and built landscape of the UK. Slashed pensions, political polarization, and crumbling infrastructure were the hallmarks of an administration whose disastrous attempt at warmongering in the Falkland Islands was rivaled only by its attrition of trade unions at home.

If the economic well-being of the British citizen could not be recovered, at least some distracting totems from days of yore could be. In 1980, months of debate over the preservation of historic properties led to the National Heritage Act, which, as Lords Mawbry and Stourton then explained it to the House of Lords, was “a memorial to everything in the past always”—insofar as those things were landed estates. Heritage was a cottage industry, too: This moment saw the ascendancy of the period drama, substantiated in a spate of Merchant Ivory films and ITV’s hugely successful Brideshead Revisited adaptation. A British Rail promotion advertised a limited run of “historical” train carriages with the slogan, “In the high speed world of today it’s nice to have a quick look back.”

These kinds of sentiments would almost certainly appeal to Leonora Eyre, the nostalgia-clotted heroine of Pym’s The Sweet Dove Died. For Leonora, an inveterate collector of Victorian memorabilia, history and consumption seem to go hand in hand. The sight of an enamel paperweight is enough to send her into raptures about how one wishes “to have lived in those days.”

As with Pym’s other novels, The Sweet Dove Died renders with wry humor the foibles and contradictions of a culture of manners—the art of the polite insult, the ludicrous arbitrariness of custom. Unlike Pym’s early works, however, The Sweet Dove Died raises the suspicion that the mores of British polite society might, after all, be neither charming nor well-meaning.

It is in this novel that Pym’s social comedy bends hardest toward social critique. Leonora acts as an avatar for the incipient politics of heritage: “an archaic figure trapped in Britain’s past successes,” as Perry Anderson once described the country’s postwar society. While it’s never been the most popular of Pym’s works, The Sweet Dove Died is the most searching: It captures Pym’s ambivalent reflections on a cultural landscape that she both profited from and yet clearly saw through.

Between 1950 and 1961, Pym published six novels, all alike in their subject matter; the characteristically quaint Pym novel, as Michael Gorra once wrote, “takes place across a middle-class tea table.” Her subjects were literally parochial: the men and women (but mostly women) of white, High Church Anglican communities in provincial Southern England. Of her 11 published novels, eight feature protagonists we might call spinsters; they are often engaged, or soon to be, by novel’s end, but only three are married when we meet them. Pym’s women are employed in vague, bookish professions that, if not entirely remunerative, allow them ample time to pursue extracurriculars—Jell-O molds, parish luncheons. Tea, of course. They live in humdrum corners of postwar London, or leafy suburban villages just beyond it, where they fall into relationships with curates, vicars, and the occasional civil servant. “Mild, kindly looks and spectacles” are what Pym’s characters expect from love—and what Pym’s readers love to expect in her work.

While Pym’s themes across the first half of her career were remarkably consistent, critical favor proved less so. Her would-be seventh novel, An Unsuitable Attachment, was dismissed by her publisher in 1963 as being insufficiently contemporary—the tea parties now no longer quaint but simply out-of-date—after which she remained unpublished for 14 years. Then both Philip Larkin and Lord David Cecil heralded Pym as the “most underrated writer” of the century in a 1977 article for the Times Literary Supplement, bringing to her works widespread critical and popular acclaim. She earned a nomination for the Booker Prize and published three more novels—The Sweet Dove Died among them—before her death in 1980. Pym, one might argue, was both the beneficiary and the unwitting conscript of the new culture of nostalgia.

If Pym’s early characters are objects of nostalgia, they aren’t necessarily guilty of it—perhaps because they’re so firmly of their time. The same can’t be said of Leonora, whose Victorian fantasies and Edwardian attitudes are increasingly at odds with the present: Now “everyone [is] so young, the girls appallingly badly dressed, all talking too loudly in order to make themselves heard above the background of pop music.” She yearns for a time when her hair still had its color, when “servants were still humble and devoted.”

In the first chapter, Leonora has lunch with Humphrey Boyce, an antiques dealer, and James, his nephew and trainee. The group has only just met, the Boyces having saved Leonora from fainting at a rare books auction. Humphrey is attracted to her; James is too, “in the way that a young man might sometimes be to a woman old enough to be his mother.” Leonora recognizes Humphrey’s attention but has her sights on the more naïve, manipulable James. This meeting sets off a mess of entanglements: Leonora balances Humphrey’s interest in her with her own attempts to keep hold of James as he’s courted first by a graduate student named Phoebe and later by a guileful American, Ned.

Much of the novel takes place within the home. As with her relationships, Leonora’s flat is arranged meticulously—aquamarine paper tissues on the bureau, a Victorian flower book open in the foyer. “Somehow I feel they’re me,” she says. This comparison is more apt than Leonora might like to admit, for Pym wants us to see her as an artifact herself: patinated surfaces disguising a hollow interior. At different moments, Leonora is described as “a piece of Meissen without flaw”; “hardly human, like a sort of fossil”; and “some old fragile object.” Sometimes the comparisons are overwrought, but they drive home the point that Leonora is precious about her age. Her favorite mirror, an antique, makes her look “fascinating and ageless.” There’s a flaw in the glass that creates this effect, but it’s permissible because it massages over her perceived flaws—“the lines where there had been none before.” The analogy here, obvious to everyone but Leonora herself, pertains to the incommensurability of the ideal image and reality, maybe too with the way the ills of the past reproduce themselves in the present. Leonora’s way of seeing the world—or rather, her way of seeing what she wants to and willfully ignoring the rest—is, quite literally, distorted.

Like any good conservative, Leonora defines her life in the negative: as a reaction against. Frozen dinners, corduroy, the “cosiness of women friends,” fluorescent lighting—these are some of the things she condemns. One suspects that the characters who populate Pym’s other works would earn from Leonora the accusation of being “hopelessly middle class.” She finds persons with disabilities “too upsetting,” the elderly both “boring and physically repellent”—though Leonora herself, Pym frequently reminds us, is approaching the autumn of her own life.

The trick of Pym’s deft, multifocal narration is to expose Leonora’s perspective as ridiculous. In one early chapter, she and James go for a predinner stroll. The garden they choose for this occasion evokes for Leonora fantastical visions of “some giardino or jardin—perhaps the Estufa Fria in Lisbon.” James is more clear-eyed on the matter: “He would have preferred to sink into a chair with a drink at his elbow rather than traipse round the depressing park with its formal flowerbeds and evil-faced statue—a sort of debased Peter Pan—at one end and the dusty grass and trees at the other.” The typical attention to detail here and Pym’s strong sense of humor, barely contained, are inseparable.

It’s due to a “streak of perverseness,” Humphrey thinks, that Leonora prefers the attentions of James to his own. But if it’s perversity, it’s not the sexual sort, or not the kind involving actual sex. Reflecting on her romantic past, Leonora wonders, “had there ever really been passion, or even emotion? One or two tearful scenes in bed—for she had never enjoyed that kind of thing—and now it was such a relief that one didn’t have to worry anymore.”

No, Leonora’s real predilection is for control. “All one’s relationships have to be perfect of their kind,” she says. Predictably few are capable of meeting this standard, though Leonora works hard to ensure that those of her circle who aren’t up to snuff are at least in her obeisance. When James begins sleeping with Phoebe, Leonora furtively moves him into her spare apartment in order to better keep an eye on him. The casualty of this arrangement is less Phoebe herself than Leonora’s now-former tenant, the elderly Mrs. Fox, whose senility and “dingy Jacobean curtains” threaten to disrupt the façade of Leonora’s home life. “One will simply have to get rid of her.”

Though Leonora is able to successfully dispense with Phoebe, she finds a worthy rival for James’s affections in Ned, whose glittering personality “mak[es] Leonora seem no more than an aging overdressed woman.” Nonetheless, after Ned moves on, James crawls back to Leonora for comfort. “People do change,” she tells him—“one sees it all the time.” James, ever the font of wisdom, replies: “But not us, Leonora.” This seems precisely the problem.

Heritage discourse promises a frictionless engagement with “the past” without the baggage of history. Yet The Sweet Dove Died dramatizes the ways in which the rosy world of British heritage, with its country houses and social graces, cannot be abstracted from the material relations of exploitation that made this way of life available in the first place. Jed Esty has written that the feeling of decline often involves not only a politics of nostalgic nationalism but a “cultural attachment to obsolete modes of production”—the “golden era” of postwar manufacturing, in the case of the United States, and of imperial expropriation and slavery, in the British context. Pym is not shy about making this connection. Leonora’s fondness for the cultural relics of Victorian England bleeds quickly into a straightforward fantasy of empire, as when she imagines herself “as a beauty of the Deep South being handed from her carriage, or as a white settler.”

Historical reality often has little to do with the romantic visions of the past we conjure. This is a distinction built into the architecture of Pym’s fiction. As much as the world she renders is beloved for its rosy quaintness, her novels themselves are scarcely nostalgic for a time gone by. Modernity’s creep reveals itself in the mumblings of characters about austerity, the jeans-wearing readership of The New Statesman, and the increasing popularity of Heinz beans. The world Pym’s characters remember is on its way out, and for the most part they meet the future with ambivalence, observing curiously its loosening class hierarchies and evolving fashions. By her final novel, A Few Green Leaves (1980), the local manor seat has been sold off to an absentee businessman. Of this change, one character remarks, “all that patronage and paternalism or whatever you like to call it has been swept away, and a good thing too.” Doe-eyed traditionalists may run amok, but they’re often the object of Pym’s satire—none more than Leonora.

Still, it’s clear that, for many, the pleasure of reading Pym lies in the fantasy her novels seem to inspire. In 2008, Alida Becker wrote, “If I want literary diversion come September, I guess I’ll have to escape into the fiction of the past. At the moment, I’m leaning toward the acerbic and resolutely small-scale…. If I’m feeling kindlier, a Barbara Pym or two.” Another critic described her fiction as “an escape to a little world of England.” Like the country B&B, Pym’s novels offer the shallow reader a chance to visit the artifacts of the recent past.

These sentiments were just as present in 1979. Philip Larkin championed her fiction for its focus on what he called “ordinary sane people doing ordinary sane things…[in] the tradition of Jane Austen and Trollope.” Larkin qualified this statement later by writing that “not everyone yearns to read about S[outh] Africa or Negro homosexuals.”

Nostalgia, Pym knew, devolves quickly into nativism. This is not to exonerate Pym on the virtue of her awareness of cultural politics—an awareness that did not preclude her close collaboration with Larkin. At the same time, in her writing, her commitment is to the keen observation of social phenomena—at first, the homespun rituals of a fading culture, and later, the reactionary politics taking shape in response to that loss. For all its light-heartedness, The Sweet Dove Died’s greatest effect is less comic than horrific, achieved in the moments when Leonora’s fantasy of Victorian culture gives way to the material relations always underlying it.

It’s not difficult to imagine the reproof that Humphrey levels at Leonora for these reveries being directed at some of Pym’s critics and readers, too. “My dear Leonora,” he cautions, “you’d have found it most disagreeable, you have this romantic view of the past—and of the present too.” Leonora promptly returns to her crème de menthe.

Another pleasant interlude before we move on to politics.

Women in Italy dining together.

British Politics

LabourList <accounts@labourlist.org> Thursday 5 February 2026

By Daniel Green Bluesky / WhatsApp / X / TikTok / email us / newsletter signup

Starmer at PMQs echoes Boris Johnson’s death throes

Yesterday marked 19 months since that landslide election victory that saw Labour return to power. I remember Starmer addressing supporters the following morning, talking of a “burden removed from the shoulders of this great nation” and returning “politics to public service”. It was truly a hopeful moment – that we could move past the disappointment and despair of the Tory era and usher in a new start for our country. And yet, 19 months on from that great day, where are we? Starmer, who promised to “restore respect to politics”, admitted in Parliament he had been aware of Mandelson’s friendship with Epstein during the ambassador vetting process – and appointed him regardless.

MPs have been reported as saying that scenes in Parliament yesterday were reminiscent of the Chris Pincher affair that eventually brought down Boris Johnson. And all of this while the party fights to hold onto a seat in Greater Manchester as the forces of populism on the right and left circle like vultures, not to mention campaigns for councils across England and the devolved nations. Some MPs have said that the Prime Minister was “advised badly”, not so subtly putting the blame at Morgan McSweeney’s door. This saga is the latest blot on his record, especially after claims he was behind briefings against Wes Streeting. However, as leader of the country, the buck always stops with the Prime Minister.

Surely the continuing relationship Mandelson maintained with Epstein after his conviction should have been disqualifying enough for any role in public office, even in the absence of all the information that has now come to light. How Starmer and those around him came to the opposite conclusion is beyond me. This is only the latest example of where Starmer has demonstrated a lack of political nous, with a series of self-inflicted wounds from multiple U-turns after spending considerable political capital defending contentious policies, from changes to inheritance tax for farmers to digital ID. Even as he tried to clear up the mess from Mandelson, Starmer was only spared an embarrassing Commons defeat by the intervention of Angela Rayner.

In the Commons yesterday, the Prime Minister said he felt betrayed for what Mandelson had done to the country, Parliament and the Labour Party. For what it’s worth, I feel betrayed by Keir Starmer – for tarnishing the party’s reputation with this ill-thought-through appointment, a reputation that he had spent four years bringing out of the gutter after that dismal night in 2019.

A sea of bad decisions coming from Number 10 have drowned out all the positive measures the government has taken. Starmer has taken the rare opportunity afforded by a Labour government with a sizeable majority and squandered it. Decisions made by this Prime Minister will cost councillors, MSPs and MSs their jobs in just over three months’ time without a change of course. Commentators and many Labour MPs have taken to the media to question whether Keir Starmer and Morgan McSweeney can weather this storm, with the Prime Minister said to be in crisis talks with his senior team. The deathly silence of the Labour benches during PMQs yesterday was extremely telling.

Labour has genuinely changed the country in ways that will have lasting effects, but the party is – and has always been – bigger than the person at the top. If Keir Starmer has become a distraction from this good work, it is perfectly reasonable for MPs, councillors or members knocking on doorsteps across the country to raise the questions they are asking. I write this with a great deal of melancholy – Starmer does come across as a man in politics for all the right reasons, but as Prime Minister has been found wanting.

But a question that remains unanswered is no doubt on the minds of many Labour MPs today – if not Starmer, then who?

I don’t want to talk about it

LabourList <accounts@labourlist.org Friday 6 February 2026

By Emma BurnellBluesky / WhatsApp / X / TikTok / email us / newsletter signup

How you broke our hearts… I would like nothing more than to focus on all the good things Labour is doing. The Employment Rights Act; the Warm Homes Plan; the Child Poverty Strategy; the strategy to tackle violence against women and girls; building social housing; Great British Energy; Great British Railways; scrapping the two child benefit cap.

I want to tell you what a great speech Keir Starmer made yesterday where he talked about Pride in Place and raised his eyes to the horizon beyond this vital project to give one of the clearest and best articulations of what this government’s agenda is that I have heard for some time. It was a speech that genuinely moved me. It reminded me once again of why having a Labour government matters.

It is our job at LabourList to bring you the good news about Labour delivering in office and we take great pride in doing it.

But the only reason we can be trusted when we report on the good that Labour is doing in government is that we are also clear-eyed when things are not good. When things are bad we have to say so. Not out of a sense of journalistic muckraking or political troublemaking. Not because we are following the herd or want to be in with the cool kids. We do so because we owe it to the government and party we support and the readers who support us to be honest. It is our job to report on what the Party is talking about, what those covering the party are talking about and what we, the Labour members and activists who also work at LabourList are talking about. It is our job to report on, analyse and aid understanding of the Labour Party. That means all aspects of it.

So we have to talk about the first half of that speech – an apology to the victims of Epstein who were once again sidelined and ignored by those in power. We have to cover the horrific actions of Peter Mandelson and the ongoing fallout from them. We have to ask the questions everyone is asking about the judgement of those who endangered their own project by being cavalier about what was already known about Mandelson and too willing to take a very risky bet there was nothing more to come. We have to talk about the culture that allowed that risk to be downplayed.

Because when Keir Starmer says “no one is above accountability” that includes his accountability to Labour members – from MPs to Councillors to lowly leaflet deliverer like myself. And LabourList is a part of that accountability. There are so many things in terms of policy that the government is getting right. There is so much being done that will change lives in the immediate and long term. We want to be able to dedicate our time to talking about them. But we can only do that if the mistakes stop overshadowing the achievements. We can only do that if the narrative becomes more powerful than the negative. We will continue to write about the good the government is doing. We will continue to report on the hard work of Labour politicians and campaigners at all levels up and down the country. And you can trust that we mean it because we do not look away from the hard truths. However much we wish we could.

American Politics

They Aren’t Acting Like They Might Lose

Open Letters, from Anne Applebaum <anneapplebaum@substack.com>

Forwarded this email? Subscribe here for more

They Aren’t Acting Like They Might Lose

Get prepared for attempts to manipulate the midterms

Anne Applebaum Feb 7

Last December, my Atlantic colleague David Graham argued that Donald Trump’s plan to subvert the midterms is already underway He updated his article here, last week, because this is an evolving story. When Trump talks about “nationalizing elections,” when he sends the FBI to raid a Georgia election center, when he and his minions talk constantly about non-citizens voting, something that is extraordinarily rare, pay attention. They are telling us that they are planning to distort the playing field, or to sully the result.

Elections are the topic of the fifth episode of this season of Autocracy in America. We start with Dawn Baldwin Gibson, a pastor in New Bern, North Carolina. She’s one of more than 60,000 North Carolina voters who had the legitimacy of their vote challenged in 2024. It might surprise many other Americans to know that your vote can be questioned after you have cast it, but it happened to her, and she is determined not to let it happen again:

“My maternal grandfather, Frederick Douglas Fisher—both of his parents were slaves. He believed in being a part of the American democracy process, and that process was voting, and that we, as his children and grandchildren, had a responsibility to show up and vote, and so there was a great pride in that. And to know that we are now in a time where we are seeing our votes being challenged, it is our responsibility. The breaking down of democracy is not going to happen on our watch. This is our time, where history will look back and say, In 2025, there were people that stood and said: “I will be seen. I will be heard, and my vote will count.”

I also talked to Stacey Abrams, whose work has helped me understand that voter suppression isn’t a single thing or a law, but rather a thousand little cuts and changes, maybe designed to discourage just a few voters, but which can make a big difference when elections are as close as ours. Abrams founded Fair Fight, the voting-rights organization, and she twice ran for governor of Georgia. She’s also the lead organizer of a campaign to fight authoritarianism called the 10 Steps Campaign. She points out that the arguments we are having about gerrymandering have some new aspects:We have never had a president of the United States explicitly state that the line should be redrawn, not based on population, but based on voter outcome. And when you do that, when you decide that the districts are not designed to allow voters to elect their leaders, it is designed to allow leaders to elect their voters—that is a shift of power, and it is exactly what redistricting is designed to preclude.We also talked about how ICE might be used on election day (we recorded our conversation before Steve Bannon explicitly called for ICE to “surround the polls come November) as well as the takeover of TikTok and other tactics that could be used, or are being used, to shape the outcome. This was her conclusion:We could win. But we are very, very, very likely to lose if we keep treating this as business as usual. This is not about whether this Democrat wins or that Republican wins. This is about whether democracy wins or authoritarianism wins.Listen or read the transcript here, on the Atlantic website. You can also find the audio on your favorite podcast platform: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | YouTube | Overcast | Pocket Casts

To keep track of this story, follow Stacey’s Substack: Assembly Notes by Stacey Abrams Assembly Notes is where I share ideas, stories, and strategies—from politics to writing to the work of building a better world.

Australian Politics

The Conversation

Author: Adrian Beaumont Election Analyst (Psephologist) at The Conversation; and Honorary Associate, School of Mathematics and Statistics, The University of Melbourne

Disclosure statement

Adrian Beaumont does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Republished under:

The South Australian state election will be held on March 21. Preferential voting will be used to elect members for all 47 single-member lower house seats. This is the same system as used for federal House of Representatives elections.

Some Australian conservatives are advocating Australia return to first past the post (FPTP), but a conservative government introduced preferential voting in 1918 to stop vote splitting between two conservative parties. Right-wing preferences helped the Coalition maintain its grip on power from 1949 to 1972. Preferential voting is far superior to FPTP.

After Labor’s landslide at the May 2025 federal election, some right-wingers have complained that preferential voting gave Labor too many seats. They want Australia to revert to FPTP, where there are no preferences. In FPTP, the candidate with the most votes wins the seat.

National primary votes at the election were 34.6% Labor, 31.8% Coalition, 12.2% Greens, 6.4% One Nation and 15.0% for all Others. After preferences, Labor defeated the Coalition by 55.2–44.8 and won 94 of the 150 House of Representatives seats (63% of seats). In both two-party and seat share, this was Labor’s biggest win since 1943.

While Labor’s margin expanded after preferences, they won the national primary vote by 2.8%. Analyst Kevin Bonham said that on primary votes, Labor would have won 86 seats to 57 for the Coalition (actual 94 to 43). Labor’s primary votes were much more efficiently distributed than the Coalition’s.

Labor won a disproportionate seat share at the election, but this occurs with single-member systems, particularly with a blowout result. Those complaining about Labor’s big majority should advocate switching to proportional representation, not FPTP.

Start your day with evidence-based news.

The United Kingdom 2024 election was held using FPTP. Labour won 411 of the 650 seats (63% of seats) on 33.7% of the national vote. This occurred primarily because Labour’s vote share was ten points ahead of the second placed Conservatives.

A brief history of preferential voting in Australia

Prior to 1918, federal elections used FPTP. In 1918, there was a byelection for Swan that was contested by the Nationalists (a predecessor of the Liberals), the Country Party (a predecessor of the Nationals) and Labor.

Labor won this byelection with 34.4%, to 31.4% for the Country Party and 29.6% for the Nationalists. With the combined vote for the two conservative options adding to 61.0%, it was clear a different system would have given the Country Party the win.

After this byelection, the Nationalist government introduced preferential voting, resulting in Labor losing the Corangamite byelection in 1918 to a Victorian Farmers candidate by 56.3–43.7, despite Labor winning the primary vote by 42.5–26.4 with 22.9% for the Nationalists.

Originally preferential voting was introduced to allow the two conservative parties (now Liberals and Nationals) to compete against each other without splitting the conservative vote and giving Labor wins it didn’t deserve. There are still “three-cornered” contests now where the Liberals, Nationals and Labor all contest the same seat.

This Wikipedia page gives national primary votes for Labor, the Coalition and all Others, the Labor and Coalition estimated two-party share and House seats won by Labor, Coalition and others at elections from 1910 to 2022.

Until the 1990s, the combined primary votes for the major parties was around 90% in most elections. This means that other than in three-cornered contests, preferences had limited impact. There were high Other votes in 1931, ‘34, ’40 and ’43, with the first three cases due to a Labor split (New South Wales Lang Labor).

In the first two of these cases, Labor was far behind on primary votes and made up some ground on preferences, but the Coalition still won easily. In 1940, Labor trailed by 3.7% on primary votes but won the two-party vote by 50.3–49.7. However, the Coalition formed government with the support of two independents until those independents sided with Labor in 1941.

In 1943, there was a split within the Coalition, and other preferences favoured the Coalition, reducing Labor’s primary vote lead of 26.9 points to 16.4 points after preferences.

In 1955, a Labor faction split from Labor and became the Democratic Labor Party (DLP), directing preferences to the Coalition. From 1955 until the DLP’s demise in 1974, it dominated the third party vote, and so overall preferences in this period assisted the Coalition.

The DLP helped the Coalition to have the longest period of one-party government from 1949 to 1972. Labor was estimated to have won the two-party vote in 1954, 1961 and 1969, but the Coalition won a majority of House seats.

Since 1987, preferences have favoured Labor, allowing it to overturn primary vote deficits to win the two-party vote in 1987, 2010 and 2022. First the Democrats and then the Greens assisted Labor after preferences. One Nation’s first rise at the 1998 election didn’t stop overall preferences from favouring Labor.

The only time Labor formed government while losing the two-party vote occurred in 1990, when they won a majority of seats despite losing by 50.1–49.9. Labor lost the election in 1998, even though it won the two-party vote by 51.0–49.0.

Some recent polls have One Nation surging into second place behind Labor, ahead of the Coalition. On current polling, there are more right-wing sources of preferences than left-wing sources, so overall preference flows could favour the right at the next federal election, whether it’s One Nation or the Coalition that benefits most.

In early elections, some seats were often uncontested, meaning only one candidate nominated for that seat. No votes were counted in such seats, so national primary votes will be distorted by the exclusion of these seats.

Why preferential voting is superior to FPTP

At the 2025 election, Labor’s Ali France defeated Liberal leader Peter Dutton in his seat of Dickson by 56.0–44.0. But Dutton had more primary votes than France, winning 34.7% of the primary vote to 33.6% for France, with 12.2% for a teal independent, 7.6% for the Greens and 4.2% for One Nation.

FPTP gives a massive benefit to the side of politics (left or right) that has its vote more concentrated with one party or candidate. In the two 1918 byelections, the left vote was concentrated with Labor, and in Dickson 2025 the right vote was concentrated with Dutton. Preferential voting is far fairer by allowing all candidates’ votes to eventually count.

In FPTP, many voters need to choose between supporting the candidate they most prefer even if that candidate is uncompetitive, and voting for the candidate best placed to keep someone they dislike out. Votes for uncompetitive candidates are effectively wasted in FPTP.

Labor may have won Dickson under FPTP as some of the teal and Greens voters would probably have voted for Labor tactically to beat Dutton. But voters shouldn’t need to make these choices.

Parliaments require majorities to function. The party winning the most seats does not necessarily form government, for example Labour formed government after the 2017 New Zealand election even though the conservative National won the most seats.

In the UK, the Conservatives needed to form alliances with other parties after winning the most seats but not a majority at the 2010 and 2017 elections. Preferential voting is closer to parliamentary systems than FPTP.

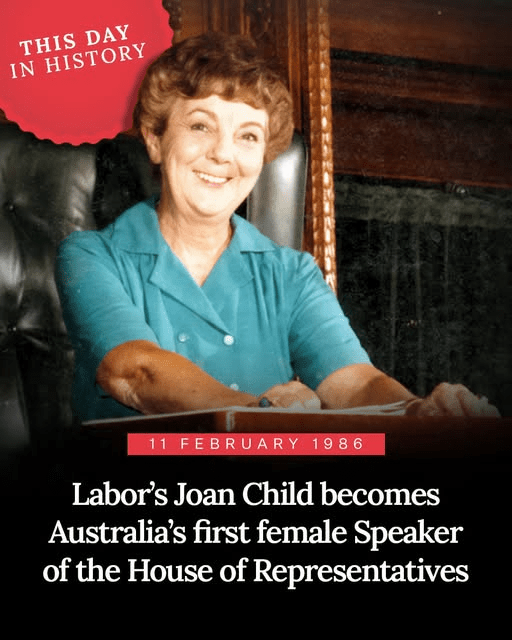

Australian Labor Party’s post

Joan Child was elected to the Melbourne seat of Henty in 1974, becoming the first female Labor member of the House of Representatives, and only the fourth woman ever elected to the House. She was Australia’s first female Speaker of the house of Representatives. Joan Child died in 2013, aged 91.

I wanted to kick off my newsletters this year with some genuinely exciting news – Labor’s $792 million women’s health package turns one this week, and it’s already making a real difference in women’s lives.

Across the country, 660,000 women have saved more than $73 million since we made contraceptives, endo and menopause medication cheaper last year.

Here in Canberra alone, more than 16,000 women have benefitted, saving a combined $1.64 million on 46,000 cheaper prescriptions.

Australian women deserve to have their health issues taken seriously and treated as a priority. That’s why this package included important changes to make Medicare work better for women – from new Medicare items to higher rebates for essential care.

Since our changes came into effect:71,000 women have accessed a Medicare-covered menopause health assessment An additional 430,000 services to help women with complex gynaecological conditions like endometriosis, polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) and chronic pelvic painAnd all 33 of our Endo and Pelvic Pain Clinics are up and running right around the country, including one here in Canberra. We’ll keep building on the progress in 2026.

Since January 1, PBS medicines are now just $25 – the lowest price since 2004.

And we’re also developing national clinical guidelines for perimenopause and menopause, along with Australia’s first national awareness campaign to better support women and the health professionals who care for them.

For too long, women have told us they faced the same barriers again and again – healthcare that was too expensive or too hard to access, and a system that too often didn’t listen.

We’ve changed that by backing these reforms with real investment, delivering women more choice, lower costs and better access to services and treatments.

I’d love to hear from you if you’ve got feedback on this policy or anything else we’re working on!

Katy Gallagher

Senator for the ACT

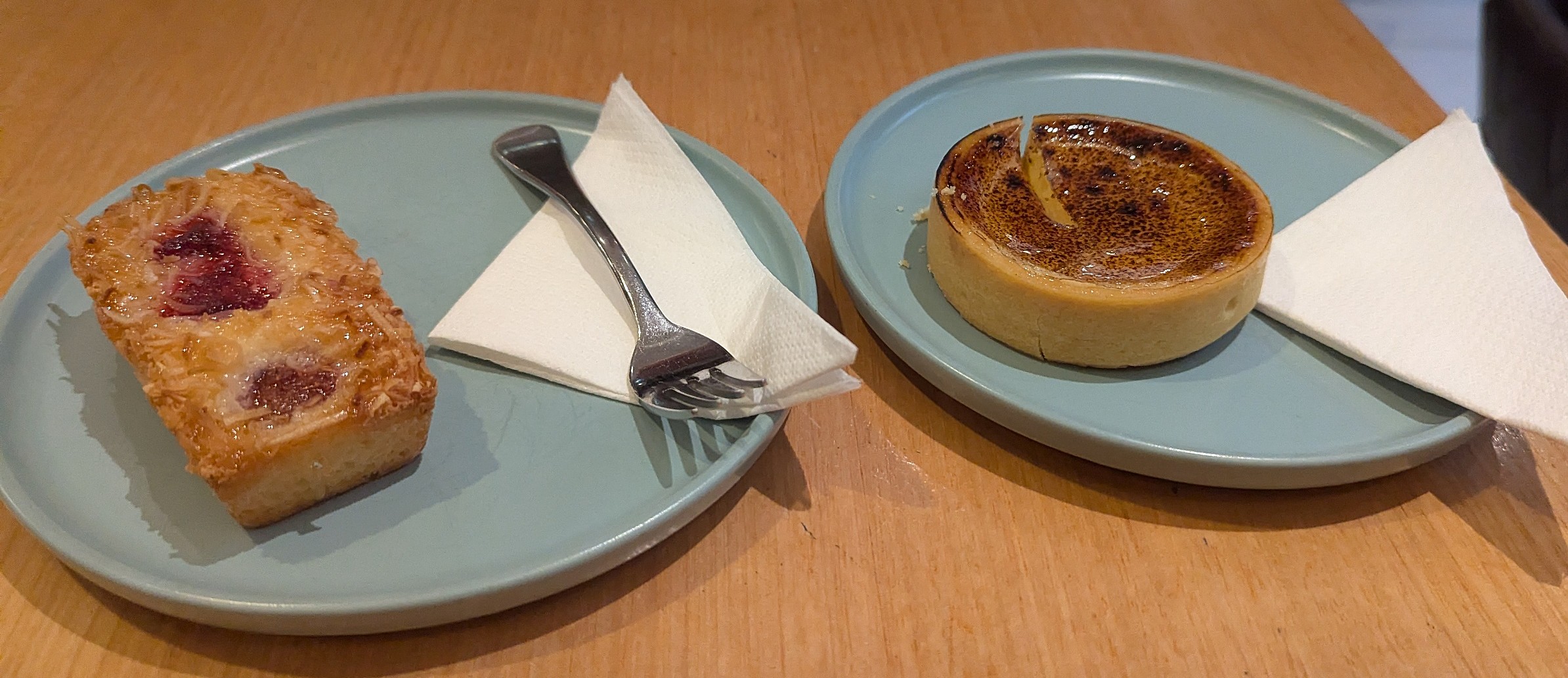

Cindy Lou has coffee at Creamery & Co

We were choosing one cake to share…but alas, it was close to closing time, so a wonderful surprise was brought to our table with the generous and delicious coffees.

Cindy Lou also went to 86, but forgot her phone, so although the food looked marvellous and was as delicious as usual – no photos. Another booking will be made. On this occasion we feasted on the chicken parfait with rhubarb jam, a delicious salad of tomato, peach, plum and basil leaves with a sauce catering to a fish allergy (the usual sauce is dashi, which the couple next to us pronounced excellent), our favourite Schezwan eggplant and another favourite, the pumpkin tortellini in a burnt butter and sage sauce.