- all material in this section is copyright to Robin Joyce (unless attributed to another author).

This section includes some book reviews where they are relevant to the commentary.

Notes from Heather Cox Richardson 28 March 2026 – Notes: https://www.nytimes.com/live/2026/us/minneapolis-shooting-ice/1f84e779-0bca-5a4a-8f50-5c79afbeabd4https://www.nytimes.com/live/2026/us/minneapolis-shooting-ice/108890fb-be19-5718-9f56-786ed1b3958dhttps://www.nytimes.com/live/2026/us/minneapolis-shooting-ice/8404e3b2-1720-5936-9b0b-55aea7fcff4bhttps://www.cnn.com/us/live-news/ice-minneapolis-shooting-01-24-26?post-id=cmksrkzmi000k3b6pgzs16rayhttps://www.startribune.com/ice-raids-minnesota/601546426https://www.democracydocket.com/news-alerts/attorney-general-bondi-minnesota-voter-rolls-border-patrol-fatal-shooting/https://iq.govwin.com/neo/marketAnalysis/view/DHS-Funding-Provisions-in-the-One-Big-Beautiful-Bill-Act/8497https://www.wpr.org/news/the-man-killed-by-a-federal-officer-in-minneapolis-was-an-icu-nurse-family-sayshttps://www.splcenter.org/resources/hatewatch/stephen-millers-affinity-white-nationalism-revealed-leaked-emails/https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.mnd.230788/gov.uscourts.mnd.230788.4.0.pdfYouTube:shorts/hyqtAyuI8LIX:TheDemocrats/status/2015109925412700479?s=20DHSgov/status/2015115351797780500?s=20Bluesky:seanokane.bsky.social/post/3md6y2b5xa22latrupar.com/post/3md6zon4a4j2dpatdeklotz.bsky.social/post/3md6zn3x5ck2vchicyph80.bsky.social/post/3md6zlv52ac2edimitridrekonja.bsky.social/post/3md6xdjppvs27simonwdc.bsky.social/post/3md6wp7tqa223petermorley.bsky.social/post/3md6rwhcrqc2xpbump.com/post/3md6xhxw47k2zpiperformissouri.bsky.social/post/3md6utaxsh22fatrupar.com/post/3md6qwufxms2sreichlinmelnick.bsky.social/post/3md76borpls2cgomez.house.gov/post/3md76w5zids23charlotteclymer.bsky.social/post/3md76ilmo6c2dgelliottmorris.com/post/3md6tocfxxs2jsahilkapur.bsky.social/post/3md7g75pv2s23esqueer.net/post/3md7e62sjtk25obarcala.bsky.social/post/3md77ysayes2zadamjschwarz.bsky.social/post/3md7bx7llxc25acyn.bsky.social/post/3md7b3wt72t2ekenklippenstein.bsky.social/post/3md75h7mhis2kjeffrueter.bsky.social/post/3md7iqqr5622imusicologyduck.bsky.social/post/3md6wrft7cs24atrupar.com/post/3md6rzvjvx22adavidcorn.bsky.social/post/3md6xn43hn22qchrismurphyct.bsky.social/post/3md6w3h4pwk2ksanho.bsky.social/post/3md7tkdg2os26ag.state.mn.us/post/3md7pjqoihc2yrickhasen.bsky.social/post/3md7o7llmok2tkyledcheney.bsky.social/post/3md7y3pdxv72vbritculpsapp.bsky.social/post/3md6xioc3ds2u

The AI revolution is here. Will the economy survive the transition?

The Substack Post <post+unstacked@substack.com> 10 January 2026

Forwarded this email? Subscribe here for more

The AI revolution is here. Will the economy survive the transition?

The man who predicted the 2008 crash, Anthropic’s co-founder, and a leading AI podcaster jump into a Google doc to debate the future of AI—and, possibly, our lives.

Michael Burry, Dwarkesh Patel, Patrick McKenzie, and Jack Clark

Michael Burry called the subprime mortgage crisis when everyone else was buying in. Now he’s watching trillions pour into AI infrastructure, and he’s skeptical. Jack Clark is the co-founder of Anthropic, one of the leading AI labs racing to build the future. Dwarkesh Patel has interviewed everyone from Mark Zuckerberg to Tyler Cowen about where this is all headed. We put them in a Google doc with Patrick McKenzie moderating and asked: Is AI the real deal, or are we watching a historic misallocation of capital unfold in real time?

The story of AI

Patrick McKenzie: You’ve been hired as a historian of the past few years. Succinctly narrate what has been built since Attention Is All You Need. What about 2025 would surprise an audience in 2017? What predictions of well-informed people have not been borne out? Tell the story as you would to someone in your domain—research, policy, or markets.

Jack Clark: Back in 2017, most people were betting that the path to a truly general-purpose system would come from training agents from scratch on a curriculum of increasingly hard tasks, and through this, create a generally capable system. This was present in the research projects from all the major labs, like DeepMind and OpenAI, trying to train superhuman players in games like Starcraft, Dota 2, and AlphaGo. I think of this as basically a “tabula rasa” bet—start with a blank agent and bake it in some environment(s) until it becomes smart. Of course, as we all know now, this didn’t actually lead to general intelligences—but it did lead to superhuman agents within the task distribution they were trained on. At this time, people had started experimenting with a different approach, doing large-scale training on datasets and trying to build models that could predict and generate from these distributions. This ended up working extremely well, and was accelerated by two key things: the Transformer framework from Attention Is All You Need, which made this type of large-scale pre-training much more efficient, and the roughly parallel development of “Scaling Laws,” or the basic insight that you could model out the relationship between capabilities of pre-trained models and the underlying resources (data, compute) you pour into them. By combining Transformers and the Scaling Laws insights, a few people correctly bet that you could get general-purpose systems by massively scaling up the data and compute. Now, in a very funny way, things are coming full circle: people are starting to build agents again, but this time, they’re imbued with all the insights that come from pre-trained models. A really nice example of this is the SIMA 2 paper from DeepMind, where they make a general-purpose agent for exploring 3D environments, and it piggybacks on an underlying pre-trained Gemini model. Another example is Claude Code, which is a coding agent that derives its underlying capabilities from a big pre-trained model.

Patrick: Due to large language models (LLMs) being programmable and widely available, including open source software (OSS) versions that are more limited but still powerful relative to 2017, we’re now at the point where no further development on AI capabilities (or anything else interesting) will ever need to be built on a worse cognitive substrate than what we currently have. This “what you see today is the floor, not the ceiling” is one of the things I think best understood by insiders and worst understood by policymakers and the broader world. Every future Starcraft AI has already read The Art of War in the original Chinese, unless its designers assess that makes it worse at defending against Zerg rushes.

Jack: Yes, something we say often to policymakers at Anthropic is “This is the worst it will ever be!” and it’s really hard to convey to them just how important that ends up being. The other thing which is unintuitive is how quickly capabilities improve—one current example is how many people are currently playing with Opus 4.5 in Claude Code and saying some variation of “Wow, this stuff is so much better than it was before.” If you last played with LLMs in November, you’re now wildly miscalibrated about the frontier.

Michael Burry: From my perspective, in 2017, AI wasn’t LLMs. AI was artificial general intelligence (AGI). I think people didn’t think of LLMs as being AI back then. I mean, I grew up on science fiction books, and they predict a lot, but none of them pictured “AI” as something like a search-intensive chatbot.For Attention Is All You Need and its introduction of the transformer model, these were all Google engineers using Tensor, and back in the mid-teens, AI was not a foreign concept. Neural networks, machine learning startups were common, and AI was mentioned a lot in meetings. Google had the large language model already, but it was internal. One of the biggest surprises to me is that Google wasn’t leading this the whole way given its Search and Android dominance, both with the chips and the software. Another surprise is that I thought application-specific integrated circuits (ASICs) would be adopted far earlier, and small language models (SLMs) would be adopted far earlier. That Nvidia has continued to be the chip for AI this far into inference is shocking. The biggest surprise to me is that ChatGPT kicked off the spending boom. The use cases for ChatGPT have generally been limited from the start—search, students cheating, and coding. Now there are better LLMs for coding. But it was a chatbot that kicked off trillions in spending. Speaking of that spending, I thought one of the best moments of Dwarkesh’s interview with Satya Nadella was the acknowledgement that all the big software companies are hardware companies now, capital-intensive, and I am not sure the analysts following them even know what maintenance capital expenditure is.

Dwarkesh Patel: Great points. It is quite surprising how non-durable leads in AI so far have been. Of course, in 2017, Google was far and away ahead. A couple years ago, OpenAI seemed way ahead of the pack. There is some force (potentially talent poaching, rumor mills, or reverse engineering) which has so far neutralized any runaway advantages a single lab might have had. Instead, the big three keep rotating around the podium every few months. I’m curious whether “recursive superintelligence” would actually be able to change this, or whether we should just have a prior and strong competition forever.

Jack: On recursion, all the frontier labs are speeding up their own developers using AI tools, but it’s not very neat. It seems to have the property of “you’re only as fast as the weakest link in the chain”—for instance, if you can now produce 10x more code but your code review tools have only improved by 2x, you aren’t seeing a massive speedup. A big open question is whether it’ll be possible to fully close this loop, in which case you might see some kind of compounding R&D advantage.Do AI tools actually improve productivity?

Dwarkesh: The million-dollar question is whether the METR productivity study (which shows that developers working in codebases they understood well had a roughly 20% decrease on merging pull requests from coding tools) or human equivalent time horizons of self-contained coding tasks (which are already in the many-hours range and doubling every four to seven months) is a better measure of how much speedup researchers and engineers at labs are actually getting. I don’t have direct experience here, but I’d guess it’s closer to the former, given that there isn’t a great feedback verification loop and the criteria are open-ended (maintainability, taste, etc.).Jack: Agreed, this is a crucial question—and the data is conflicting and sparse. For example, we did a survey of developers at Anthropic and saw a self-reported 50% productivity boost from the 60% of those surveyed who used Claude in their work. But then things like the METR study would seem to contradict that. We need better data and, specifically, instrumentation for developers inside and outside the AI labs to see what is going on. To zoom out a bit, the massive and unprecedented uptake of coding tools does suggest people are seeing some major subjective benefit from using them—it would be very unintuitive if an increasing percentage of developers were enthusiastically making themselves less productive.

Dwarkesh: Not to rabbit hole on this, but the self-reported productivity being way higher than—and potentially even in the opposite direction of—true productivity is predicted by the METR study.

Jack: Yes, agreed. Without disclosing too much, we’re thinking specifically about instrumentation and figuring out what is “true” here, because what people self-report may end up being different from reality. Hopefully we’ll have some research outputs on this in 2026!Which company is winning?

Michael: Do you think the podium will keep rotating? From what I’m hearing, Google is winning among developers from both AWS and Microsoft. And it seems the “search inertia” has been purged at the company.

Dwarkesh: Interesting. Seems more competitive than ever to me. The Twitter vibes are great for both Opus 4.5 and Gemini 3.5 Pro. No opinion on which company will win, but it definitely doesn’t seem settled.Jack: Seems more competitive than ever to me, also!

Dwarkesh: Curious on people’s take on this: how many failed training runs/duds of models could Anthropic or OpenAI or Google survive? Given the constant need to fundraise (side question: for what exactly?) on the back of revenue and vibes.

Michael: The secret to Google search was always how cheap it was, so that informational searches that were not monetizable (and make up 80% or more) did not pile up as losses for the company. I think this is the fundamental problem with generative AI and LLMs today—they are so expensive. It is hard to understand what the profit model is, or what any one model’s competitive advantage will be—will it be able to charge more, or run cheaper?Perhaps Google will be the one that can run cheapest in the end, and will win the commodity economy that this becomes.

Dwarkesh: Great point. Especially if you think many/most of the gains over the last year have been the result of inference scaling, which requires an exponential increase in variable cost to sustain.Ultimately, the price of something is upper-bounded by the cost to replace it. So foundation model companies can only charge high margins (which they currently seem to be) if progress continues to be fast and, to Jack’s point, becomes eventually self-compounding.Why hasn’t AI stolen all our jobs?

Dwarkesh: It’s really surprising how much is involved in automating jobs and doing what people do. We’ve just marched through so many common-sense definitions of AGI—the Turing test is not even worth commenting on anymore; we have models that can reason and solve difficult, open-ended coding and math problems. If you showed me Gemini 3 or Claude 4.5 Opus in 2017, I would have thought it would put half of white-collar workers out of their jobs. And yet the labor market impact of AI requires spreadsheet microscopes to see, if there is indeed any.I would have also found the scale and speed of private investment in AI surprising. Even as of a couple years ago, people were talking about how AGI would have to be a government, Manhattan-style project, because that’s the only way you can turn the economy into a compute and data engine. And so far, it seems like good ol’-fashioned markets can totally sustain multiple GDP percentages of investment in AI.

Michael: Good point, Dwarkesh, re: the Turing test—that was definitely the discussion for a good while. In the past, for instance, during the Industrial Revolution and the Services Revolution, the impacts on labor were so great that mandatory schooling was instituted and expanded to keep young people out of the labor pool for longer. We certainly have not seen anything like that.

Jack: Yes, Dwarkesh and Michael, a truism for the AI community is they keep on building supposedly hard tasks that will measure true intelligence, then AI systems blow past these benchmarks, and you find yourself with something which is superficially very capable but still likely makes errors which any human would recognize as bizarre or unintuitive. One recent example is LLMs were scored “superhuman” on a range of supposedly hard cognitive tasks, according to benchmarks, but were incapable of self-correcting when they made errors. This is now improving, but it’s an illustration of how unintuitive the weaknesses of AI models can be. And you often discover them alongside massive improvements.

Dwarkesh: I wonder if the inverse is also true—humans reliably make classes of errors that an LLM would recognize as bizarre or unintuitive, lol. Are LLMs actually more jagged than people, or just jagged in a different way?

Patrick: Stealing an observation from Dwarkesh’s book, a mundane way in which LLMs are superhuman is that they speak more languages than any human—by a degree that confounds the imagination—and with greater facility than almost all polyglots ever achieve. Incredibly, this happens by accident, even without labs specifically training for it. One of the most dumbfounding demos I’ve ever seen was an LLM trained on a corpus intended to include only English documents yet able to translate a CNN news article to Japanese at roughly the standard of a professional translator. From that perspective, an LLM that hadn’t had politeness trained into it might say, “Humans are bizarre and spiky; look how many of them don’t speak Japanese despite living in a world with books.”Why many workers aren’t using AI (yet)

Patrick: Coding seems to be the leading edge for widespread industrial adoption of AI, with meteoric revenue growth for companies like Cursor, technologists with taste taking to tools like Claude Code and OpenAI Codex, and the vibes around “vibe coding.” This causes a pronounced asymmetry of enthusiasm for AI, since most people are not coders. What sector changes next? What change would make this visible in earnings, employment, or prices rather than demos?

Jack: Coding has a nice property of being relatively “closed loop”—you use an LLM to generate or tweak code, which you then validate and push into production. It really took the arrival of a broader set of tools for LLMs to take on this “closed loop” property in domains outside of coding—for instance, the creation of web search capabilities and the arrival of stuff like Model Context Protocol (MCP) connectivity has allowed LLMs to massively expand their “closed loop” utility beyond coding. As an example, I’ve been doing research on the cost curves of various things recently (e.g. dollars of mass to orbit, or dollars per watt from solar), and it’s the kind of thing you could research with LLMs prior to these tools, but it had immense amounts of friction and forced you to go back and forth between the LLM and everything else. Now that friction has been taken away, you’re seeing greater uptake. Therefore, I expect we’re about to see what happened to coders happen to knowledge workers more broadly—and this feels like it should show up in a diffuse but broad way across areas like science research, the law, academia, consultancy, and other domains.

Michael: At the end of the day, AI has to be purchased by someone. Someone out there pays for a good or service. That is GDP. And that spending grows at GDP rates, 2% to 4%—with perhaps some uplift for companies with pricing power, which doesn’t seem likely in the future of AI.Economies don’t have magically expanding pies. They have arithmetically constrained pies. Nothing fancy. The entire software pie—SaaS software running all kinds of corporate and creative functions—is less than $1 trillion. This is why I keep coming back to the infrastructure-to-application ratio—Nvidia selling $400 billion of chips for less than $100 billion in end-user AI product revenue.AI has to grow productivity and create new categories of spending that don’t cannibalize other categories. This is all very hard to do. Will AI grow productivity enough? That is debatable. The capital expenditure spending cycle is faith-based and FOMO-based. No one is pointing to numbers that work. Yet.There is a much simpler narrative out there that AI will make everything so much better that spending will explode. It is more likely to take spending in. If AI replaces a $500 seat license with a $50 one, that is great for productivity but is deflationary for productivity spend. And that productivity gained is likely to be shared by all competitors.

Dwarkesh: Michael, isn’t this the “lump of labor” fallacy? That there’s a fixed amount of software to be written, and that we can upper bound the impact of AI on software by that?

Michael: New markets do emerge, but they develop slower than acutely incentivized futurists believe. This has always been true. Demographics and total addressable market (TAM) are too often marketing gimmicks not grounded in reality. China’s population is shrinking. Europe’s is shrinking. The U.S. is the only major Western country growing, and that is because of immigration, but that has been politicized as well. FOMO is a hell of a drug. You look at some comments from Apple or Microsoft, and it seems they realize that.

Dwarkesh: As a sidenote, it’s funny that AI comes around just when we needed it to save us from the demographic sinkhole our economies would have otherwise been collapsing into over the next few decades.Michael: Yes, Dwarkesh. In medicine, where there are real shortages, there is no hope for human doctors to be numerous enough in the future. Good medical care has to become cheaper, and technology is needed to extend the reach and coverage of real medical expertise.Are engineers going to be out of work?

Patrick: AppAmaGooFaceSoft [Apple, Amazon, Google, Facebook, Microsoft] presently employ on the order of 500,000 engineers. Put a number on that for 2035 and explain your thinking—or argue that headcount is the wrong variable, and name the balance-sheet or productivity metric you’d track instead.

Michael: From 2000, Microsoft added 18,000 employees as the stock went nowhere for 14 years. In fact headcount barely moved at Cisco, Dell, and Intel, despite big stock crashes. So I think it is the wrong variable. It tells us nothing about value creation, especially for cash-rich companies and companies in monopoly, duopoly, or oligopoly situations. I think it will be lower, or not much higher, because I think we are headed for a very long downturn. The hyperscalers laid off employees in 2022 when their stocks fell, and hired most of them back when their stocks rose. This is over a couple years.I would track shareholder-based compensation’s (SBC) all-in cost before saying productivity is making a record run. At Nvidia, I calculated that roughly half of its profit is eliminated by compensation linked to stock that transferred value to those employees. Well, if half the employees are now worth $25 million, then what is the productivity gain on those employees? Not to mention, margins with accurate SBC costs would be much lower.The measure to beat all measures is return on invested capital (ROIC), and ROIC was very high at these software companies. Now that they are becoming capital-intensive hardware companies, ROIC is sure to fall, and this will pressure shares in the long run. Nothing predicts long-term trends in the markets like the direction of ROIC—up or down, and at what speed. ROIC is heading down really fast at these companies now, and that will be true through 2035.In his interview with Dwarkesh, Satya Nadella said that he’s looking for software to maintain ROIC through a heavy capital expenditure cycle. I cannot see it, and even to Nadella, it sounds like only a hope.

Dwarkesh: Naive question, but why is ROIC more important than absolute returns? I’d rather own a big business that can keep growing and growing (albeit as a smaller fraction of investment) than a small business that basically prints cash but is upper-bounded in size.So many of the big tech companies have lower ROIC, but their addressable market over the next two decades has increased from ads ($400 billion in revenue a year) to labor (tens of trillions in revenue a year).

Michael: Return on invested capital—and, more importantly, its trend—is a measure of how much opportunity is left in the company. From my perspective, I have seen many roll-ups where companies got bigger primarily through buying other companies with debt. This brings ROIC into cold focus. If the return on those purchases ends up being less than the cost of debt, the company fails in a manner akin to WorldCom.At some point, this spending on the AI buildout has to have a return on investment higher than the cost of that investment, or there is just no economic value added. If a company is bigger because it borrowed a lot more or spent all its cash flow on something low-return, that is not an attractive quality to an investor, and the multiple will fall. There are many non-tech companies printing cash with no real prospects for growth beyond buying it, and they trade at about 8x earnings.Where is the money going?

Patrick: From a capital-cycle perspective, where do you think we are in the AI build-out—early over-investment, mid-cycle shakeout, or something structurally different from past tech booms? What would change your mind?

Michael: I do see it as different from prior booms, except in that the capital spending is remarkably short-lived. Chips cycle every year now; data centers of today won’t handle the chips of a few years from now. One could almost argue that a lot of this should be expensed, not capitalized. Or depreciated over two, three, four years.Another big difference is that private credit is financing this boom as much as or more than public capital markets. This private credit is a murky area, but the duration mismatch stands out—much of this is being securitized as if the assets last two decades, while giving the hyperscaler outs every four to five years. This is just asking for trouble. Stranded assets. Of course, the spenders are the richest companies on earth, but whether from cash or capital markets, big spending is big spending, and the planned spending overwhelms the balance sheets and cash flow of even today’s massive hyperscalers.Also, construction in progress (CIP) is now an accounting trick that I believe is already being used. Capital equipment not yet “placed into service” does not start depreciating or counting against income. And it can be there forever. I imagine a lot of stranded assets will be hidden in CIP to protect income, and I think we are already seeing that potential.In Dwarkesh’s interview, Nadella said he backed off some projects and slowed down the buildout because he did not want to get stuck with four or five years of depreciation on one generation of chips. That is a bit of a smoking-gun statement.We are mid-cycle now—past the point where stocks will reward investors for further buildout, and getting into the period where the true costs and the lack of revenue will start to show themselves.In past cycles, stocks and capital markets peaked about halfway through, and the rest of the capital expenditure occurred as a progressively pessimistic, or realistic, view descended on the assets of concern.

Dwarkesh: I think this is so downstream of whether AI continues to improve at a rapid clip. If you could actually run the most productive human minds on a B200 (Nvidia’s B200 GPU), then we’re obviously massively underinvesting. I think the revenues from the application layer so far are less informative than raw predictions about progress in AI capabilities themselves.

Jack: Agreed on this—the amount of progress in capabilities in recent years has been deeply surprising and has led to massive growth in utilization of AI. In the future, there could be further step-change increases in model capabilities, and these could have extremely significant effects on the economy. What the market gets wrong

Patrick: Where does value accrue in the AI supply chain? How is this different from recent or historical technological advances? Who do you think the market is most wrong about right now?

Michael: Well, value accrues, historically, in all industries, to those with a durable competitive advantage manifesting as either pricing power or an untouchable cost or distribution advantage.It is not clear that the spending here will lead to that.Warren Buffett owned a department store in the late 1960s. When the department store across the street put an escalator in, he had to, too. In the end, neither benefited from that expensive project. No durable margin improvement or cost improvement, and both were in the same exact spot. That is how most AI implementation will play out.This is why trillions of dollars of spending with no clear path to utilization by the real economy is so concerning. Most will not benefit, because their competitors will benefit to the same extent, and neither will have a competitive advantage because of it.I think the market is most wrong about the two poster children for AI: Nvidia and Palantir. These are two of the luckiest companies. They adapted well, but they are lucky because when this all started, neither had designed a product for AI. But they are getting used as such.Nvidia’s advantage is not durable. SLMs and ASICs are the future for most use cases in AI. They will be backward-compatible with CUDA [Nvidia’s parallel computing platform and programming model] if at all necessary. Nvidia is the power-hungry, dirty solution holding the fort until the competition comes in with a completely different approach.Palantir’s CEO compared me to [bad actors] because of an imagined billion-dollar bet against his company. That is not a confident CEO. He’s marketing as hard as he can to keep this going, but it will slip. There are virtually no earnings after stock-based compensation.

Dwarkesh: It remains to be seen whether AI labs can achieve a durable competitive advantage from recursive self-improvement-type effects. But if Jack is right and AI developers should already be seeing huge productivity gains, then why are things more competitive now than ever? Either this kind of internal “dogfooding” cannot sustain a competitive advantage or the productivity gains from AI are smaller than they appear.If it does turn out to be the case that (1) nobody across the AI stack can make crazy profits and (2) AI still turns out to be a big deal, then obviously the value accrues to the customer. Which, to my ears, sounds great.

Michael: In the escalator example, the only value accrued to the customer. This is how it always goes if no monopoly rents can be charged by the producers or providers.What would change their minds

Patrick: What 2026 headline—technological or financial—would surprise you and cause you to recalibrate your overall views on AI progress or valuation? Retrospectively, what was the biggest surprise or recalibration to date?

Michael: The biggest surprise that would cause me to recalibrate would be autonomous AI agents displacing millions of jobs at the biggest companies. This would shock me but would not necessarily help me understand where the durable advantage is. That Buffett escalator example again.Another would be application-layer revenue hitting $500 billion or more because of a proliferation of killer apps.Right now, we will see one of two things: either Nvidia’s chips last five to six years and people therefore need less of them, or they last two to three years and the hyperscalers’ earnings will collapse and private credit will get destroyed.Retrospectively, the biggest surprises to date are:Google wasn’t leading the whole way—the eight authors of Attention Is All You Need were all Google employees; they had Search, Gmail, Android, and even the LLM and the chips, but they fumbled it and gave an opening to competitors with far less going for them. Google playing catch-up to a startup in AI: that is mind-blowing.ChatGPT—a chatbot kicked off a multi-trillion-dollar infrastructure race. It’s like someone built a prototype robot and every business in the world started investing for a robot future.Nvidia has maintained dominance this far into the inference era. I expected ASICs and SLMs to be dominant by now, and that we would have moved well beyond prompt engineering. Perhaps the Nvidia infatuation actually held players back. Or anticompetitive behavior at Nvidia did.

Dwarkesh: Biggest surprises to me would be:2026 cumulative AI lab revenues are below $40 billion or above $100 billion. It would imply that things have significantly sped up or slowed down compared to what I would have expected.Continual learning is solved. Not in the way that GPT-3 “solved” in-context learning, but in the way that GPT-5.2 is actually almost human-like in its ability to understand from context. If working with a model is like replicating a skilled employee that’s been working with you for six months rather than getting their labor on the first hour of their job, I think that constitutes a huge unlock in AI capabilities.I think the timelines to AGI have significantly narrowed since 2020. At that point, you could assign some probability to scaling GPT-3 up by a thousand times and reaching AGI, and some probability that we were completely on the wrong track and would have to wait until the end of the century. If progress breaks from the trend line and points to true human-substitutable intelligences emerging over the next 5 to 20 years, that would be the biggest surprise to me.Jack: If “scaling hits a wall,” that would be truly surprising and would have very significant implications for both the underlying research paradigm as well as the broader AI economy. Obviously, the infrastructure buildout, including the immense investments in facilities for training future AI models, suggests that people are betting otherwise.One other thing I’d find surprising is if there was a combination of a technological breakthrough that improved the efficiency of distributed training, and some set of actors that put together enough computers to train a very powerful system. If this happened, it would suggest you can not only have open-weight models but also a form of open model development where it doesn’t take a vast singular entity (e.g. a company) to train a frontier model. This would alter the political economy of AI and have extremely non-trivial policy implications, especially around the proliferation of frontier capabilities. Epoch has a nice analysis of distributed training that people may want to refer to.How they actually use LLMs

Patrick: What was your last professionally significant interaction with an LLM? File off the serial numbers, if need be. How did you relate to the LLM in that interaction?

Michael: I use Claude to produce all my charts and tables now. I will find the source material, but I spend no time on creating or designing a professional table, chart, or visual. I still don’t trust the numbers and need to check them, but that creative aspect is in the past for me. Relatedly, I will use Claude in particular to find source material, as so much source material these days is not simply at the SEC or in a mainstream report.

Patrick: I think people outside of finance do not understand how many billions of dollars have been spent having some of the best-paid, best-educated people in the world employed as Microsoft PowerPoint and Excel specialists. There is still value in that, for the time being, and perhaps the shibboleth value of pivot tables and VLOOKUP() will endure longer than they do, but my presentation at the Bank of England also used LLMs for all the charts. It feels almost bizarre that we once asked humans to spend hours carefully adjusting them.

Dwarkesh: They are now my personal one-on-one tutors. I’ve actually tried to hire human tutors for different subjects I’m trying to prep for, and I’ve found the latency and speed of LLMs to just make for a qualitatively much better experience. I’m getting the digital equivalent of people being willing to pay huge premiums for Waymo over Uber. It inclines me to think that the human premium for many jobs will not only not be high, but in fact be negative.

Michael: On that point, many point to trade careers as an AI-proof choice. Given how much I can now do in electrical work and other areas around the house just with Claude at my side, I am not so sure. If I’m middle class and am facing an $800 plumber or electrician call, I might just use Claude. I love that I can take a picture and figure out everything I need to do to fix it.Risk, power, and how to shape the future

Patrick: The spectrum of views on AI risk among relatively informed people runs the gamut from “it could cause some unpleasantness on social media” to “it would be a shame if China beat the U.S. on a very useful emerging technology with potential military applications” to “downside risks include the literal end of everything dear to humanity.” What most keeps you up at night? Separately, if you had five minutes with senior policymakers, what new allocation of attention and resources would you suggest?

Jack: The main thing I worry about is whether people succeed at “building AI that builds AI”—fully closing the loop on AI R&D (sometimes called recursively self-improving AI). To be clear, I assign essentially zero likelihood to there being recursively self-improving AI systems on the planet in January 2026, but we do see extremely early signs of AI getting better at doing components of AI research, ranging from kernel development to autonomously fine-tuning open-weight models. If this stuff keeps getting better and you end up building an AI system that can build itself, then AI development would speed up very dramatically and probably become harder for people to understand. This would pose a range of significant policy issues and would also likely lead to an unprecedented step change in the economic activity of the world, attributable to AI systems. Put another way, if I had five minutes with a policymaker, I’d basically say to them, “Self-improving AI sounds like science fiction, but there’s nothing in the technology that says it’s impossible, and if it happened it’d be a huge deal and you should pay attention to it. You should demand transparency from AI companies about exactly what they’re seeing here, and make sure you have third parties you trust who can test out AI systems for these properties.”

Michael: Jack, I imagine you have policymakers’ ears, and I hope they listen.AI as it stands right now does not worry me much at all, as far as risks to humanity. I think chatbots have the potential to make people dumber—doctors that use them too much start to forget their actual innate medical knowledge. That is not good, but not catastrophic. The catastrophic worries involving AGI or artificial superintelligence (ASI) are not too worrying to me. I grew up in the Cold War, and the world could blow up at any minute. We had school drills for that. I played soccer with helicopters dropping Malathion over all of us. And I saw Terminator over 30 years ago. Red Dawn seemed possible. I figure humans will adapt.

If I had the ear of sen

When our arts desk asked 20 experts to list the books that got them through their 20s, I doubt they expected one of them to come back with Heart of Darkness. A mesmerising work of genius, sure, but a companion to surviving early adulthood? When I read the explanation as to why this book made it on to the list, however, I was immediately convinced. I think that’s why this two-part series – the second of which we published this week – has proven so popular. It’s an unexpected reading list for an uncertain period in anyone’s life. Madame Bovary isn’t a character you would want to emulate in your 20s but her story has a lot to teach us, so it made the cut. In fact, there’s arguably something to offer readers of any age in the lineup and certainly inspiration for Christmas pressies for the young people in your life.

Laura hood Senior Politics Editor, Assistant Editor

Your 20s can be an intense decade. In the words of Taylor Swift, those years are “happy, free, confused and lonely at the same time”. Many of us turn to literature to guide us through the highs and the lows of this formative time. We asked 20 of our academic experts to recommend the book that steered them through those ten years.

The complete article appears at Further Commentary and Articles arising from Books* and continued longer articles as noted in the blog. However, the list of books dealt with in more detail there, appears below.

1. Butterfly Burning by Yvonne Vera (1998)

Growing up, I didn’t have much guidance in discovering Black writers, especially not Black women writers. I’d read African classics like Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart (1958), Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s Devil on the Cross (1980), or Amos Tutuola’s The Palm-Wine Drinkard (1952), but I found it hard to connect with them.

As a young woman I was drawn to feminist and poetic writing about the body rather than political parables about places I’d never been to. That’s why Butterfly Burning – a fiercely poetic and mysteriously intimate novel – was such a revelation.

In 1997, Vera described her practice in a short essay called Writing Near the Bone. There she recalled her earliest memories of writing: being sent outside with her cousins where they would play by tracing their names in the mud and dust covering their legs. “We wrote deep into the skin and under skin where the words could not escape.” If a sentence can be a muse, this was destined to become mine.

Mathelinda Nabugodi is a lecturer in comparative literature

2. The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro (1989)

Do you lie awake at night wondering what it would be like to work as a butler in a magnificent British manor during the first half of the 20th century? No? Still, it’s hard to escape such thoughts while reading Kazuo Ishiguro’s masterful 1989 novel The Remains of the Day.

The protagonist, Stevens, strives to become a “great” butler, which – according to him – means being able to carry out his duties even in the most extreme circumstances.

Emotions have no place in that job description, which leads to tragic consequences. Stevens is unable to express his deep feelings for his colleague Miss Kenton. Nor does he question his employer Lord Darlington’s political misjudgments.

The novel is a brilliant portrayal of class divisions and restrained masculinity – alas, traits not limited to a bygone era. In many ways, these are timeless themes. We must all reflect on how we balance our inner butler in our daily lives.

Torbjörn Forslid is a professor in literary studies

3. The History Man by Malcolm Bradbury (1975)

The History Man is my favourite campus novel. Like most successful satires, it pinballs between funny and bleak.

It follows an academic year in the life of sociology professor Howard Kirk, his wife Barbara, students and colleagues. His alternate charming and bullying outraged moralists and feminists on the book’s release.

After the #MeToo campaign, Howard is yet more likely to be termed emotionally and sexually abusive. I read the book the year I started teaching and immediately put it on my syllabus. Some cohorts loved it, some loathed it. Either reaction from my class of 20-somethings was better than indifference.

The political and activist energy of youth will be recognisable to many in their 20s, though the book cautions readers to consider who is agitating and why. It confronts readers with unethical and unjust scenarios in workplace and social settings that, unfortunately, will still be relatable to many young people – even if, today, their responses might differ from those of the characters.

Sarah Olive is a senior lecturer in English literature

4. Palestine by Joe Sacco (1993)

I was 25 when I first read Joe Sacco’s Palestine. Drawn in serialised chapters in the early 1990s, in the wake of the first intifada and on the eve of the Oslo accords, Sacco’s non-fiction comic offers a snapshot of history that will open your eyes to the deprivations of the Israeli occupation of Gaza.

It overturned the west’s media blackout on the Palestinian experience when it was first published, and it continues to serve as urgent testimony to the suffering of civilians who have lived their whole lives under settler colonial power. Sacco maintains his self-deprecating style throughout, reflexively satirising his reader’s consumption of war and violence as entertainment and bringing the architecture of the occupied territories to life.

Palestine will make you see through to the roots of conflict and feel the thickness of history as a force that accumulates in real people’s lives – in their eyes, their bodies, their homes, their landscapes.

Dominic Davies is a Reader in English

5. Lost Illusions by Honoré de Balzac (1843)

Reading Lost Illusions profoundly shaped my 20s. It follows Lucien de Rubempré, a poor young poet from the provinces who arrives in Paris full of idealism, believing talent alone ensures success. He soon learns that literary success in Paris depends more on corruption, social connections and birth than on merit.

The novel prepared me for my own “loss of illusions”. In my youth, I joined the 2011 India Against Corruption movement and protests in Delhi, convinced that corruption could be eradicated overnight. That movement later became a political party which now faces corruption charges. Like many young people back then, I believed in the possibility of overnight transformation, only to confront the disappointments of reality and the slow nature of change.

What makes Balzac’s novel valuable for people in their 20s is how it celebrates romantic idealism through the Cénacle (a group of idealist characters) all the while preparing readers, through Lucien’s story, for inevitable disillusionment.

Harsh Trivedi is a teaching associate in French studies

6. Hotel Du Lac by Anita Brookner (1984)

I bought Anita Brookner’s Hotel Du Lac at the Brookline Booksmith in Boston, having been stunned by the author’s other novel, Look at Me (1983). I was 25, acquisitive and impulsive, and newly caught up in the restive and wordy life of US grad school.

The protagonist, Edith Hope, is a writer of romance novels. She’s banished to the damp solitude of a Swiss hotel, with its assortment of affluent misfits, melancholics and the inveterately companionless. A hopeless affair and an abandoned wedding in her wake, Edith tries to restart her writing here, now that domesticity had been set aside like the “creditable” Chanel copy that was her bridal suit.

That novel is not written, the heart hardly mended, but she dodges another disastrous proposal. I credit this novel for teaching me the aliveness of being unhoused, benumbed, and lonely. How to be tortoise reader, not a hare, for “hares have no time to read”.

Ankhi Mukherjee is Professor of English and World Literatures

7. Never Far From Nowhere by Andrea Levy (1996)

Andrea Levy’s most acclaimed novels are those released in the early 21st century, but her 1990s novels are some of my favourites, and were important to me during my 20s.

Never Far From Nowhere is a coming-of-age story that follows sisters Olive and Vivien, born in London to Jamaican parents. The book’s perspective alternates between sisters, and readers are brought into the very different lives they lead as they navigate diasporic identities, violence, racism, colourism friendships and more.

As a Caribbean woman raised in London, this book was influential in my 20s because of the carefulness with which Levy writes characters who are raised between places and cultures, and the way she explores strategies for belonging for her “third culture” characters (“third culture” refers to people who are raised in different cultures to that of their parents). This novel, as with all of Levy’s work, probes the intimate and fluid relationship between Britain and the Caribbean through prose that is beautifully crafted and full of heart.

Leighan Renaud is a lecturer in the Department of English

8. The Long Goodbye by Raymond Chandler (1953)

In my 20s I undertook a PhD examining representations of war trauma in the work of American crime writer Raymond Chandler. At the time, the Iraq and Afghanistan wars were intensifying, with misinformation over the so-called war on terror’s effectiveness and a lack of transparency leading to mistrust and suspicion.

The Long Goodbye – where the “long goodbye” becomes a metaphor for the slow erosion of trust, friendship and human closeness in a commodified, cynical age – fit the era well. Chandler transforms the hardboiled story into a humanist meditation on the struggle to remain moral in a corrupt and dehumanising world.

Chandler revealed a deeply moral and human-centered worldview to me, where integrity triumphed over corruption, and human flaws and weaknesses were treated with compassion and empathy. This humanistic perspective developed further in me as I watched nightly accounts of increasing military casualties. It echoed Chandler’s existential humanist concerns: how to live authentically in a world without clear moral or spiritual certainty.

Sarah Trott is a senior lecturer in American studies and history

9. The City by Valerian Pidmohylnyi (1928)

If there is one book I could recommend to any 20-year-old, it would be The City by Ukrainian writer, Valerian Pidmohylnyi. The English translation is beautifully written by Maxim Tarnawsky.

It follows an ambitious young writer who has just arrived in a capital city and has to sleep in a shed of a friend of a friend to make ends meet. He enters university and starts his path to glory, using any means necessary to get the private apartment he covets in a bohemian neighbourhood, where he imagines sitting with a morning coffee and writing a bestseller.

Whether they’re living in early 20th century Kyiv, or today’s Edinburgh or London, there are certain things that young people want – and Pidmohylnyi captures them. The novel is sharp, very honest and bitingly funny. It’s a book you need to read in your twenties, then return to it in your thirties – it will hit some very different notes a decade on.

Viktoriia Grivina is a PhD candidate in energy ethics

10. The Mezzanine by Nicholson Baker (1988)

For many people, their 20s are their point of entry into the world of work. The lucky ones find professional fulfilment. Others, however, discover with horror that they are doing what the anthropologist David Graeber famously called “bullshit jobs”. Rather than feeling creative or empowered, they occupy one (or more) of the roles that Graeber identifies in the modern workplace: “flunkies,” “goons”, “duct tapers”, “box tickers” and “taskmasters”.

Nicholson Baker’s wonderfully distinctive short novel, The Mezzanine (1988), offers respite from such stultification. Howie, its narrator, toils as a corporate drudge. Far from letting routine work matters absorb his thoughts, however, he allows his mind to take flight, dwelling for pages at a time on esoteric things such as drinking straws, staplers and footnotes (of which, quirkily, this novel is full).

The book stages a polite rebellion against the conformist professional life. Reading it in your 20s, as soon as you start to feel such pressures, will help to keep your imagination open.

Andrew Dix is a senior lecturer in American literature and film

Part 2

11. A Manor House Tale by Selma Lagerlöf (1899)

To be young is to feel alone with your suffering. Whatever has happened to you – a broken heart, bullying, your parents’ divorce, a death – you feel you are alone with your fate. No one else understands how much it hurts, no one tells you how it really is.

In my own 20s, I felt less alone by reading the older classics. In particular, the Swedish Nobel prize laureate Selma Lagerlöf’s gothic novel A Manor House Tale moved me deeply. The portrayal of two young people who fall in love, yet are separated by mental illness and financial hardship, taught me something about love beyond superficial dating and convention.

It helped me understand that love is the strength to endure the deepest darkness for the sake of the other, and how difficult that is. Both protagonists are struck by mental illness, and each must struggle with their own affliction to be able to receive love.

Katarina Båth is a senior lecturer in comparative literature

12. To the Lighthouse by Virginia Woolf (1927)

When I first encountered Woolf’s work, her prose struck me as impossibly, infuriatingly vague. Luckily for me, her novels were required reading on the course I was taking, so I had no choice but to persevere. It took a while for my inner ear to attune to the poetry of her rhythmical cadences; but once I learnt to attend to them properly, they utterly transformed my sense of what writing could be.

It took time, too, for my life to catch up with the existential and elegiac tenor of Woolf’s writing. Loss and grief came to me in my 20s, and amid the utter devastation of those times it was to Woolf that I turned. To the Lighthouse, in particular – in which she reconjures her childhood and the parents she had lost decades before – afforded me a powerful sense of recognition.

Amid the sorrow it evokes, I marvelled at Woolf’s depiction of many moments of “ecstasy” and “rapture” arising from the most mundane situations – moments which, in their radiance, seemed to point to the importance of living on.

Scarlett Baron is an associate professor of 20th- and 21st-century literature

13. The Best of Everything by Rona Jaffe (1958)

I surprised myself with this choice. Standing before my bookshelf, full of colourful spines, broken and creased, evidence of stories told and read, my fingers reached for an unsuspecting novel: The Best of Everything.

It was given to me by a friend who sometimes knows me better than I know myself. I first heard about it from the actor Sarah Jessica Parker, who said that without it, Sex and the City would not exist. The book reaches for a certain universality. I am sceptical of that word, but I do wonder: What touches us all?

As a Black woman, it might seem unlikely I would find fragments of myself in four white women in 1950s New York, yet I do. In the quiet recognitions, the man who does not love you back, the first day you realise what you are good at, the sudden throb of ambition, the book crystallises something electric. It bottles the shock of adulthood that strikes every 20-something-year-old. Who am I? And what do I want?

Olumayokun Ogunde is a doctoral researcher in English

14. Candide by Voltaire (1759)

When I turned 23, I landed a graduate IT role for an international bank. It was a long commute to a pretty, northern city so daily, for an hour each way, I read.

Reading made late trains, weather and crowded buses tolerable. It wasn’t what I’d imagined after my English degree and master’s but I appreciated it, and had been awarded a place on a competitive employee environmental project in the Kalahari desert (I still lament leaving before taking up this opportunity).

One week, I reread Voltaire’s Candide. Candide is about journeys, changes and seeking “the best of all possible worlds”. Violent, impossible, ridiculous and laconic, it turned me into an annoyingly vocal reader. Suddenly, I knew I must return to university – I started my PhD soon after.

Candide’s desperate situations and peaks and troughs of optimism and despair shook me out of my routine during my 20s, a rare period in life when I could change direction. I recommend it for anyone seeking encouragement to take a calculated risk.

Jenni Ramone is an associate professor of postcolonial and global literature and director of the Postcolonial and Global Studies Research Group

15. The Sparrow by Mary Doria Russell (1996)

What does it mean to have a calling? And what do you do when that calling betrays you and leads the people you love to unbearable suffering? Mary Doria Russell’s novel The Sparrow ostensibly tells the story of Emilio Sandoz, a Jesuit priest and linguist who joins a mission to the planet Rakhat to translate the language of its inhabitants, but these questions burn at its heart.

I first read The Sparrow in my mid-20s, fighting to balance my newfound vocation to progressive Christian ministry with multiple family members’ deaths and the unravelling of a young marriage. For many, our 20s are a time when we struggle to define who we are and what we are called to do in the world. Both inspiring and harrowing, The Sparrow speaks to that struggle – and to the discernment we must use to avoid doing more harm than good as we wage it.

The Reverend Tom Emanuel is PhD candidate in English literature.

16. The Song of Achilles by Madeline Miller (2011)

The Song of Achilles came out right at the beginning of my PhD in classics. It was the start of my 20s, and I’d just become interested in how fiction can challenge the classical canon, especially epics like Homer’s.

I’d been reading Margaret Atwood’s The Penelopiad, and I’d begun writing the early chapters (though I didn’t know it then) of what would become my first novel, For the Most Beautiful (itself a retelling of the Iliad, through the women). And then Madeline Miller came to Yale, and I heard her speak about what it means to retell stories as she does. I read (or rather, devoured) her beautiful book, and something clicked.

There is nothing more powerful than to have trailblazers like Miller who lay the path. The Song of Achilles is a masterful, gorgeous, timeless novel that I come back to again and again. I would encourage anyone in their 20s who wants to know that there is more than one way of telling a story – and that that can be its own story and its own gift, in itself – to turn to this book.

Emily Hauser is a senior lecturer in classics

17. The God of Small Things by Arundhati Roy (1997)

I first read this stunning, Booker prize-winning novel at the age of 22, as part of my master’s degree at the University of Edinburgh.

At the time, I was reading voraciously for classes, sometimes getting through a book a day. But Roy’s opening chapter, a challenging piece that contains all the elements of the story she’s about to tell, stopped me in my tracks because of its beauty, tragedy and complexity. I was instantly hooked.

Set in Kerela, India, The God of Small Things traces the lives of fraternal twins, Rahel and Estha, and their extended family from the late 1960s to the early 1990s. Roy puts the small stories of the family’s life into conversation with the big narratives and structures that shape Indian society over this period. The book’s revelations enthralled me in terms of plot, while Roy’s stylistic innovations and intricate structuring (her training as an architect perhaps played a role here) made it a mesmerising read.

The God of Small Things examines the specifics of Indian society such as (de)colonisation and caste while also speaking to questions of family, death and ultimately, love. It is a novel to savour at any age but since it’s one worth returning to, reading it in your 20s just means more chances to do so!

Ellen Howley is an assistant professor in the School of English

18. Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad (1899)

Heart of Darkness is crucial reading in your 20s because it contains multiple opportunities for discovery, including self-discovery. Or at least, that’s what my future self can tell my past self.

On the face of it, Conrad’s novella is a journey into the heart of Africa. It is also, though, a story about the discovery of historic injustice as it reports on Belgium’s colonial regime. To learn about colonial history is a vital education.

Less obviously, it also exposes you to a narrative style which gets you questioning how a work of fiction can play with your confidence in truth. We’re warned early on of “old sailor’s yarns” while imposters, facades and silences can be found throughout the story. Reading it in my 20s, I discovered that critical thinking and observation skills make for valuable mental equipment.

Conrad’s story teaches you how to be a better reader, a crucial skill in our times – and rewards a reader that pays attention.

Lewis Mondal is a lecturer in African American literature

19. Mrs Dalloway by Virginia Woolf (1925)

Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway (1925) came to me in my early 20s, as I was beginning to understand how the life we live inwardly rarely mirrors the one other people perceive.

Set across a single day in post-war London, the novel captures the texture of our thoughts: fleeting, associative, irrepressible. Clarissa Dalloway’s quiet crisis – was this the right life? did she love the right way? – and Septimus Smith’s descent into trauma spoke to the realisation that adulthood isn’t a destination but a continual negotiation of memory, grief and the mundane.

For readers in their 20s, Mrs Dalloway is invaluable because it resists the binary of success and failure. Instead, it explores the richness of interiority, how past selves linger in present choices, and how the smallest gestures can shape a life. Woolf teaches us that meaning is stitched not in milestones but in moments, in glances, in a solitary walk to buy flowers.

Nada Saadaoui is a PhD candidate in English literature

20. Madame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert (1856)

Since having children in my 30s, I am reduced to a sobbing ball by media in which people get depressed, or toddlers worry about things, or inanimate objects seem like they might be lonely. But in my 20s, when I was better equipped to face the realities of the human condition, I returned frequently to Madame Bovary.

It tells of Emma, a sheltered young woman who marries a kind but prosaic country doctor. Desperate for romance, she embarks on affairs and spends beyond her means, with predictably tragic results. There is some hauntingly beautiful imagery, as in the scene when Emma incinerates her wedding bouquet and watches petals flit like butterflies up the chimney.

Mainly, though, the novel reassured me that there was someone out there (albeit a fictional someone) making a bigger mess of life than me. My ill-advised student purchases included unwearable shoes, fishnet tights for the Scottish winter, and a pool table – but at least I never spent 14 francs in a month on lemons for polishing my nails.

Martha McGill is a historian of mem

Why Hitchcock’s ‘Rear Window’ Mirrors Today’s Social Media Age

In its exploration of themes like paranoia, voyeurism, and loneliness, Hitchcock’s Rear Window strikes a familiar chord with the social media climate we live in today.

By Jennifer O’Callaghan/ 28 November 2022

Rear Window Alfred Hitchcock Paramount 1 September 1954

Throughout Alfred Hitchcock’s lengthy career, the 1950s were undoubtedly his most glamorous era in filmmaking. With Hollywood’s biggest stars in Technicolor and carefully crafted sequences that would have film scholars talking for decades, Hitchcock entered a new peak in visual storytelling. Rear Window, now approaching the 70th anniversary of its production, is a standout film of that decade with a storyline that still holds relevance in the 21st century. Using the camera as narrator, Rear Window carefully weaves a terrifying thriller through a multi-layered love story. Released in 1954, Rear Window is widely regarded as one of the most accessible and modern of Hitchcock’s 53 films.

These days, Hitchcock’s legacy hardly requires an introduction, but in the early ’50s, he was an outside-of-the-box filmmaker beginning to revolutionize sound and frame editing by putting himself in the audience’s place. Rear Window was released during a trying time to a post-World War II public when fears of Communism and nuclear war generated anxiety in America. Gender stereotypes were tightly intact, and it would be over a decade before the women’s liberation movement shook up the patriarchy. Yet, when re-analyzing Rear Window in our times, it still feels as fresh as the day it was made. The paranoia and isolation experienced by the central character reflect those feelings of loneliness and mistrust in current society. Distortions of social media further mirror Rear Window’s themes, which remain universal in America.

Another reason Rear Window retains its relevance is partially due to the imperfection and relatability of its main character. J.B. Jefferies, known to his friends as Jeff (played by the reliably affable Jimmy Stewart, who even gives this curmudgeon appeal), is a flawed anti-hero. As a combat photographer who’d always been on the go, he’s now confined to a wheelchair after breaking his leg. (In an early scene, he explains the cast on his left leg is a result of getting too close for comfort with his camera at an auto race.) Jeff spends his days of recovering, staring aimlessly through the back window of his Greenwich Village apartment into the courtyard below—and into the windows of his neighbors.

Enter Lisa Fremont (Grace Kelly), a glamourous career girl of Madison Avenue who’s mad about Jeff. Though deeply frustrated at his lack of commitment, she doesn’t back down easily, even if it means going out on a limb to show him her dangerous side. Jeff also receives daily visits from Stella (played by the spunky Thelma Ritter), his nurse who serves as the voice of reason. She does her best to convince him he’s making a mistake by casting Lisa aside. Flabbergasted at the thought of Jeff ending things with her because she’s “too perfect”, Stella sighs, “I can hear you now: “Get out of my life, you wonderful woman. You’re too good for me.”

Jeff, who seems too wrapped up in himself to take Lisa seriously, spends the entirety of Rear Window observing different walks of life through a camera lens at his back window, the same point of view that Hitchcock cleverly limits the audience. Bored to tears, he spies on neighbors, inventing stories about their lives. The curiosities in this intimate setting fulfill Jeff’s overactive imagination. The audience becomes one with him as he leaps from one conclusion to another about the narrow view he has of people he doesn’t know. His act of observing others from a secure, unseen distance isn’t unlike our online world today.

Navigating social media platforms with similar access to friends and strangers can result in the same lack of connection Jeff is experiencing in his inner life (perhaps even more so in a post-pandemic world). When we indulge in social media to feel more connected to others, known and unknown, the nature of these platforms creates a further sense of disconnection and, like Jeff’s predicament, isolates us from our real-life networks, leading to more loneliness. The ’50s-era Rear Window demonstrates that people have always had the same counterproductive tendencies to overcome loneliness. It’s no wonder Rear Window‘s commentary on humanity remains ageless.

Though certain aspects of Rear Window, like the fashions and technology of the ’50s are of its era, its underlying messages on the common feeling of alienation and the tendency to judge others from a distance remains a tale as old as time. Upon release, film critic Bosley Crowther of The New York Times summed it up well, stating, “It exposes many facets of the loneliness of city life and it tacitly demonstrates the impulse of morbid curiosity.”

Stewart’s Jeff makes one wonder if they’d genuinely like him upon meeting him. On one hand, he is played with great charm by the most “Regular Joe” movie star of all time. (Visions of Stewart usually bring to mind the wholesome George Bailey in Frank Capra’s 1946 film It’s a Wonderful Life, happily embracing his family on Christmas Day). From another angle, Jeff spends his days and nights with a camera – out of sheer boredom at being stuck inside – peeping into other’s windows. Though, with the blinds up in many of these apartments, it could be debated that some of these characters possibly want to be seen. This is comparable to the exhibitionism we see in the desired accumulation of “likes” in the social media world. As much as online privacy protection has been discussed in the media, people still want to be seen and positively acknowledged.

As Jeff scans his neighbors’ windows, he makes snap judgments about who they are. He looks down on the loved-up newlyweds and the bickering old couple as he rejects the “suffocating” institution of marriage for himself. He dubs the shapely dancer who entertains male suitors “Miss Torso”, and the unmarried woman who entertains imaginary dates in the next apartment over “Miss Lonelyhearts”. Jeff’s behavior shares similarities with the comments sections of many social media platforms. People anonymously pass judgment and make snide remarks about others, yet in the real world, they wouldn’t dare say such things face to face.

Jeff’s old-world misogyny doesn’t allow him to see much about these women beyond what they physically represent. In his mind, women seem to belong in two categories – the “vamp” or “the spinster”. What he’s unconsciously observing in his multi-box display of domestic dramas is relationship commitment (and his potential future with Lisa) in its various stages and forms. In his mind, Lisa is from another world. Her distaste for combat boots and hostels instead of three-star hotels demonstrates a stark incompatibility between the two. Jeff views her desire to marry him as a ball and chain that will slow him down and impede his photography career.

To emphasize their differences, Hitchcock ensured Lisa Fremont’s wardrobe was considered with meticulous detail for every scene. When meeting with legendary Hollywood costume designer, Edith Head, he stressed that Lisa must appear so perfect that she’s almost untouchable. Head needed to create a nearly unattainable dream-like air about Lisa. Drawing inspiration from Christian Dior’s post-war “New Look”, the costumes range from an elegant monochromatic dress with a full white skirt and off-the-shoulder top to a pistachio-colored suit with a tailored white halter top. The on-camera effect is breathtaking as Lisa enters and leaves his apartment. The visual contrast of her exquisite clothes next to the dingy apartment and Jeff’s baggy pajamas further emphasize the different worlds Lisa and Jeff aspire to.

When Lisa first appears, Hitchcock uses a clever trick by shaking the camera for a shimmering effect. The result is a desired dream-like sequence. She whispers to Jeff.

Lisa: How’s your leg?

Jeff: Hurts a little

Lisa: Your stomach?

Jeff: Empty as a football

Lisa: And your love life?

Jeff: Not too active.

Lisa: Anything else bothering you?

Jeff: Yes—who are you?

As she moves about his small apartment to switch on his three lamps, the romantic haze slowly lifts, and reality sets in. Jeff’s defenses are up. He won’t open up to Lisa, and her exasperation mounts as, at one point, she wonders aloud, “How far does a girl have to go before you notice her?”

If Jeff is the voyeur of Rear Window and, essentially, the filmmaker who follows a killer, then Lisa is the heart of the film and the more courageous of the two in expressing her feelings and desires. “I’m in love with you,” she says plainly. ”I don’t care what you do for a living. I’d just like to be part of it somehow.” Lisa embraces life in the real world. Each night when she visits Jeff, she’s full of stories and excitement about her work day, which he resents. For almost eight weeks, he’s been stuck in a dark room with his overactive imagination, peering out and creating paranoid ideas about the world. In today’s context, Jeff represents the typical lonely internet addict, whereas Lisa embodies someone with a healthier relationship with the outside world.

Soon Jeff begins to confront the worst-case scenario of spying on his neighbors. Through his camera lens, he sees what he believes is Lars Thorwold (Raymond Burr) murdering his wife by poisoning her, then following up that horrible act by dispensing her body parts in the East River. Jeff’s world is shaken by what he’s sure he’s just witnessed. It’s one thing to stare across the courtyard and fabricate murder mysteries to pass time, but he suddenly realizes the reality of someone taking another human life is absolutely stomach-turning.

What makes Rear Window‘s murder scene unique is that it takes place out of sight with the blinds drawn. Mrs. Thorwald’s scream goes mostly unnoticed in the heat of the Manhattan summer night, and not an ounce of gore is shown. Jeff and the audience observe as Thorwald quickly moves in and out of his apartment with a heavy suitcase of presumed evidence, and we are left to conclude what it contains.

Compared to Hitchcock’s later acclaimed films like Psycho (1961) or The Birds (1963), where the violence is more blatant and intense, he made an interesting choice with Rear Window. Here, he plays on the viewer’s mounting anxiety about what may be happening instead of showing what is happening. In Psycho, the aggressive murder scene where Marion Crane (Janet Leigh) is stabbed to death on-screen in the shower by Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins) is terrifyingly effective. Rear Window’s murder is just as horrible an act, but that it happens behind closed curtains taps into the audience’s emotions of apprehension.

In his effort to prove Thorwald murdered his wife, Jeff receives help from Lisa and Stella. Unlike Jeff, trapped in his apartment, the women go out searching for concrete evidence to show the police, and they even deliver Jeff’s handwritten note to Thorwald, which simply says, “What have you done with her?” To prove her gumption and willingness to get her hands dirty, Lisa steals into Thorwald’s apartment in search of further proof of murder while he’s away. Confined to a wheelchair, Jeff (and the audience) look on with utter anxiety, as the murderer will be returning any minute. When Thorwald comes home and begins to interrogate and manhandle Lisa, Jeff falls to pieces as all he can do is peer across the courtyard in sheer agony.

The police, of course, arrive just in time, and she’s free to go. In triumph, Lisa flashes Mrs. Thorwald’s wedding ring to Jeff as she leaves the scene. Thorwald, unfortunately, catches onto this as well. For the first time, he looks across the courtyard and locks eyes with Jeff. It is a chilling moment. Jeff’s voyeurism has now been revealed, and his secretive judgment of his neighbors is no longer his private – and safe – world.

Later that night, Thorwald’s entrance into Jeff’s apartment is one of the most suspenseful climaxes of all of Hitchcock’s films. His face is unrecognizable in the blackness of the night as he taunts Jeff from the doorway. “What do you want from me?” he says sinisterly. By now, the audience has become Jeff, if you will. As a viewer, it’s impossible not to experience his feelings of paralysis and helplessness. Thorwald wastes no time trying to kill Jeff, ironically attempting to toss him out of his rear window – and succeeding. Once again, the police arrive to take Thorwald away.

The next frame shows a rough landing for Jeff, and not without further casualties. In the final scene, Jeff, now in two leg casts, is resting, notably with his back turned to the rear window. Lisa, now his caretaker, is dressed casually and resting beside him with a copy of William O. Douglas’ 1952 travel book, Beyond the High Himalayas. Just before the credits roll, as if to note that she won’t be changing herself entirely for Jeff, Lisa casts the book aside and begins to leaf through a copy of Harper’s Bazaar.

A script loaded with social commentary by John Michael Hayes and a central character conflicted in his psyche are key elements that firmly place Rear Window in the category of one of the best films of all time. Keeping the audience in a small, dark apartment along with Jeff so they hear and see exactly what he hears and sees created new territory in mainstream film back in 1954, but it has the same effect on our anxieties today. “I was feeling very creative at the time,” Hitchcock said of the Rear Window’s success. “The batteries were well charged.” (The Art of Alfred Hitchcock: Fifty Years of His Motion Pictures, 1976). In his artistic vision for Rear Window, it’s almost as if Hitchcock predicted the future of social media and voyeuristic reality television.

Going into production, Hitchcock was no stranger to working with Stewart. They had previously made Rope together in 1948 (another murder caper, which, coincidently, was also filmed entirely on one apartment). Soon after Rear Window, they made The Man Who Knew Too Much (1956) and Vertigo (1958). Kelly had also worked with Hitchcock earlier that year in Dial M for Murder (1954). They would reunite after Rear Window for To Catch a Thief (1955). When Kelly first decided to do Rear Window, she had an agonizing decision on her hands. At the same time, she had also received the script for On the Waterfront, with an offer to play Marlon Brando’s girlfriend in the film directed by Elia Kazan.

“I sat in my apartment with two screenplays—one was to be filmed in New York with Marlon Brando, and the other was going to be filmed in Hollywood, with James Stewart. Making a picture in New York suited my plans better—but working again with Hitch…well, it was a dilemma.” (High Society: The Life of Grace Kelly, 2009). She knew her destiny was to work with Hitchcock, the director she fully trusted. Besides, due to her upbringing in a prominent Philadelphia family, playing a privileged woman of New York high society was a character she deeply understood.

Rear Window received four Oscar nominations in 1955 for Best Director (Hitchcock), Best Writing (John Michael Hayes), Best Cinematography, and Best Sound. Though it shockingly didn’t take home any statues that year, it’s still considered by filmgoers, scholars, and critics to be one of the top films of American cinema. In 1997, Rear Window received the credit it deserved when the Librarian of Congress placed it on the National Film Registry.

Over time, Rear Window has set off a chain reaction of inspiration in modern films on the dangers of loneliness and self-destructive behavior. Even in recent years, it has influenced multiple voyeuristic films like Sam Mendes’ drama American Beauty (1999), a modern fable about the mid-life crisis in America and a lonely teen with a camcorder. Another example is D.J. Caruso’s crime drama Disturbia (2007), a tale taken directly from Rear Window about a teen on house arrest whose boredom leads him to suspect his next-door neighbor is a wanted serial killer.

Rear Window’s thesis seems to state that everybody’s watching everyone, but what we all need is a genuine connection. As Stella put it so aptly, “What people ought to do is get outside their own house and look in for a change.”

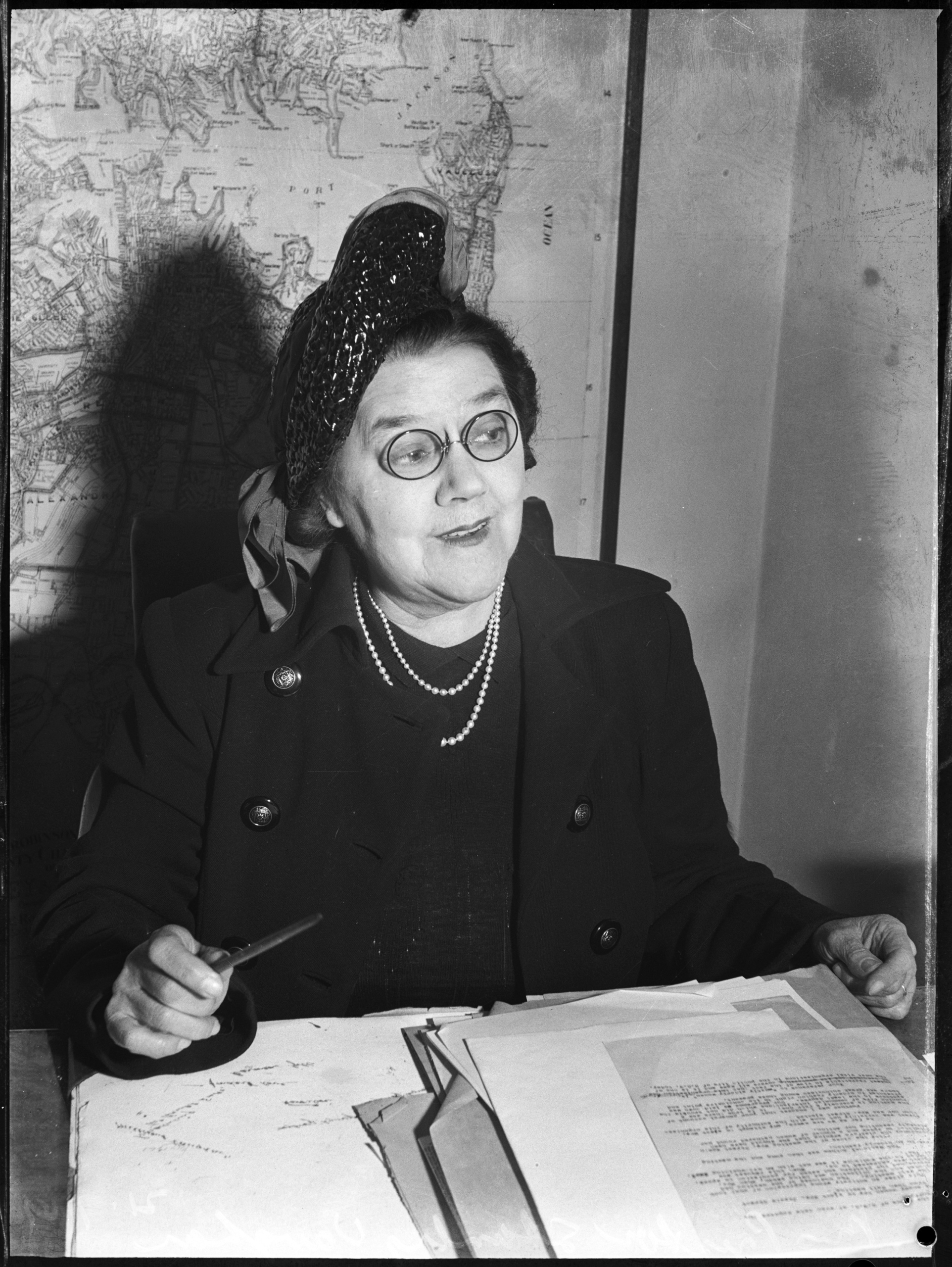

On Barbara Pym, Author… and Stalker?

Evangeline Riddiford Graham Considers the Unrequited Loves of the Celebrated Novelist

Evangeline Riddiford Graham November 17, 2025

Barbara Pym, a novelist sometimes described as the twentieth-century Jane Austen, was a stalker. Her diaries describe her methods of “finding out” her objects of interest in vivid detail: looking them up in directories, “tailing” them across town to discover their home addresses and workplaces and places of worship, staging “chance” encounters, and collecting their “relics.” She invented “sagas,” games of investigation and fantasy that could last several years. Most of her victims were men; they were, to varying degrees, unavailable. Several of them were gay.