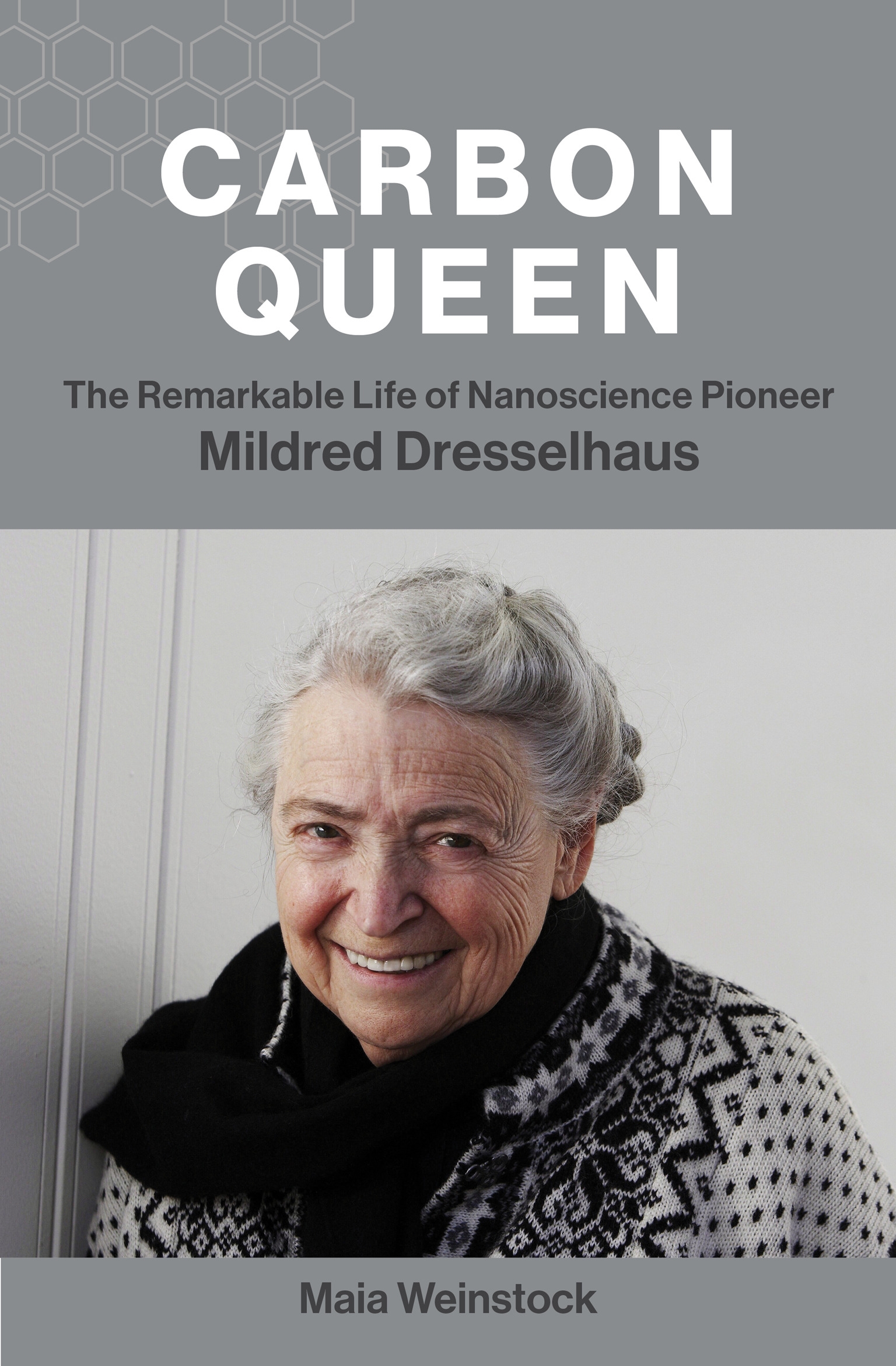

This week I review two non fiction books, Carbon Queen The Remarkable life of Nanoscience Pioneer Mildred Dresselhaus by Maia Weinstock, and Elisabeth Galvin’s The Real Kenneth Grahame The Tragedy Behind The Wind in the Willows. Both were provided to me by NetGalley as uncorrected proofs in exchange for an honest review.

Maia Weinstock Carbon Queen The Remarkable life of Nanoscience Pioneer Mildred Dresselhaus The MIT Press, 2022.

This inspiring biography begins with a stunning idea which brings to life the ‘what might be’ of women’s lives and celebratory status. At the same time as being instructive, it is heart-breaking – the fictional accounts of the accolades that Mildred Dresselhaus might have received if women were treated equally are graphic reminders that indeed they are not. Carbon Queen is the story of a woman whose accomplishments exceeded even those that the General Electric video described and enhanced in the prologue to this biography. Carbon Queen is a compelling mixture of scientific information and an account of an impressive woman’s life as scientist, academic, teacher, mentor, parent and partner drawn together by a writer whose scientific background is valuable, and understanding of women’s position is sensitive, well researched and well written. I was interested that Maia Weinstock referred to women’s work at home as well as in the paid workforce, so gently expressed, but nevertheless making a salient point. Books: Reviews for full review.

Elisabeth Galvin The Real Kenneth Grahame The Tragedy Behind The Wind in the Willows White Owl Pen & Sword 2021.

Elisabeth Galvin’s sensitive interpretation of the lives of Kenneth Grahame, Elsie Thomson, and their son Alistair, is a gentle reflection on three lives that come together, move far from each other, return with affection mixed with a massive lack of understanding, and find a way of living and parting that, while often dysfunctional, seems to have been understood in this family and amongst their friends. This is not to underestimate the tragedies they experienced, but Galvin’s work gently discusses these and then moves forward – as indeed did the adult Grahames.

Galvin’s language and the way in which she combines quotes, her interpretation, and kind reading of events in the family, their personalities and relationships with neighbours, friends and work colleagues forms a dappled patchwork of images, ideas and intuitive commentary that reflects the water and surrounds which were the background for the animal adventures in The Wind in the Willows. Galvin does not adopt the lively tone familiar in many of the Pen & Sword publications, rather her own language is quite straight forward, depending on the addition of well selected quotes to liven the narrative. I like the way Galvin’s approach harmonises with the stories with which the reader will be familiar – the language of river, woodland, four animals of very different demeanor and a narrative that lives up to the title The Real Kenneth Grahame. Books: Reviews for full review.

Articles placed after the Covid report are: Heather Cox Richardson – two articles about American politics; Zora Simic review of Difficult Women; Vanessa Thorpe, racist ‘casta’ paintings; comment on Roslyn Russell’s similar research; and article – Robert E, Lee statue and Black History Museum.

Post Covid lockdown ACT

New cases recorded in Canberra on the 30th and 31st December – 253 and 462. Active cases are now 1,658, with six patients in hospital, but none in intensive case or ventilated.

On 1 January, 2022 there were 448 new cases recorded. Quarantine rules, like those in five states and territories, changed from midnight on 31 December.

Close contacts, who receive a day 6 negative result from their test may now leave quarantine from day 7. Close contacts are required to avoid high risk settings , such as hospitals and aged care facilities for another 7 days unless seeking urgent medical care or have prior approval.

Comprehensive lists of exposure sites are updated daily.

New cases for 2 , 3 and 4 January are 506, 514 and 926. There thirteen people in hospital with one in intensive care. On 5 January 810 new cases were recorded.

Heather Cox Richardson

https://www.facebook.com/heathercoxrichardson

December 29, 2021 (Wednesday)

Yesterday, Josh Kovensky at Talking Points Memo reported that the Trump allies who organized the rally at the Ellipse at 9:00 a.m. on January 6 also planned a second rally that day on the steps of the Supreme Court. To get from one to the other, rally-goers would have to walk past the Capitol building down Constitution Avenue, although neither had a permit for a march. The rally at the Supreme Court fell apart as rally-goers stormed the Capitol.

Trump’s team appeared to be trying to keep pressure on Congress during the counting of the certified electoral votes from the states, perhaps with the intent of slowing down the count enough to throw it into the House of Representatives or to the Supreme Court. In either of those cases, Trump expected to win because in a presidential election that takes place in the House, each state gets one vote, and there were more Republican-dominated states than Democratic-dominated states. Thanks to then–Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell’s (R-KY) removal of the filibuster for Supreme Court appointments, Trump had been able to put three justices on the Supreme Court, and he had said publicly that he expected they would rule in his favor if the election went in front of the court.

This story is an important backdrop of another story that is getting oxygen: Trump trade advisor Peter Navarro’s claim that he, Trump, and Trump loyalist Steve Bannon had a peaceful plan to overturn the election and that the three of them were “the last three people on God’s good Earth who wanted to see violence erupt on Capitol Hill.” According to these stories, their plan—which Navarro dubs the Green Bay Sweep—was to get more than 100 senators and representatives to object to the counting of the certified ballots. They hoped this would pressure Vice President Mike Pence to send certified votes back to the six contested states, where Republicans in the state legislatures could send in new counts for Trump. There was, he insists, no plan for violence; indeed, the riot interrupted the plan by making congress members determined to certify the ballots.

Their plan, he writes, was to force journalists to cover the Trump team’s insistence that the election had been characterized by fraud, accusations that had been repeatedly debunked by state election officials and courts of law. The plan “was designed to get us 24 hours of televised hearings…. But we thought we could bypass the corporate media by getting this stuff televised.” Televised hearings in which Trump Republicans lied about election fraud would cement that idea in the public mind. Maybe. It is notable that the only evidence for this entire story so far is Navarro’s own book, and there’s an awful lot about this that doesn’t add up (not least that if Trump deplored the violence, why did it take him more than three hours to tell his supporters to go home?). What does add up, though, in this version of events is that there is a long-standing feud between Bannon and Trump advisor Roger Stone, who recently blamed Bannon for the violence at the Capitol. This story exonerates Trump and Bannon and throws responsibility for the violence to others, notably Stone. Although Navarro’s story is iffy, it does identify an important pattern. Since the 1990s, Republicans have used violence and the news coverage it gets to gain through pressure what they could not gain through votes. Stone engineered a crucial moment for that dynamic when he helped to drive the so-called Brooks Brothers Riot that shut down the recounting of ballots in Miami-Dade County, Florida, during the 2000 election. That recount would decide whether Florida’s electoral votes would go to Democrat Al Gore or Republican George W. Bush. As the recount showed the count swinging to Gore, Republican operatives stormed the station where the recount was taking place, insisting that the Democrats were trying to steal the election. “The idea we were putting out there was that this was a left-wing power grab by Gore, the same way Fidel Castro did it in Cuba,” Stone later told legal analyst Jeffrey Toobin. “We were very explicitly drawing that analogy.” “It had to be a three-legged stool. We had to fight in the courts, in the recount centers and in the streets—in public opinion,” Bush campaign operative Brad Blakeman said.

As the media covered the riot, the canvassing board voted to shut down the recount because of the public perception that the recount was not transparent, and because the interference meant the recount could not be completed before the deadline the court had established. “We scared the crap out of them when we descended on them,” Blakeman later told Michael E. Miller of the Washington Post. The chair of the county’s Democratic Party noted, “Violence, fear and physical intimidation affected the outcome of a lawful elections process.” Blakeman’s response? “We got some blowback afterwards, but so what? We won.”

That Stone and other Republican operatives would have fallen back on a violent mob to slow down an election proceeding twenty years after it had worked so well is not a stretch. Still, Navarro seems eager to distance himself, Trump, and Bannon from any such plan. That eagerness might reflect a hope of shielding themselves from the idea they were part of a conspiracy to interfere with an official government proceeding. Such interference is a federal offense, thanks to a law passed initially during Reconstruction after the Civil War, when members of the Ku Klux Klan were preventing Black legislators and their white Republican allies from holding office or discharging their official duties once elected.

Prosecutors have charged a number of January 6 defendants with committing such interference, and judges—including judges appointed by Trump—have rejected defendants’ arguments that they were simply exercising their right to free speech when they attacked the Capitol. Investigators are exploring the connections among the rioters before January 6 and on that day itself, establishing that the attack was not a group of individual protesters who randomly attacked at the same time, but rather was coordinated. The vice-chair of the House Select Committee to Investigate the January 6th Attack on the U.S. Capitol, Liz Cheney (R-WY), has said that the committee is looking to see if Trump was part of that coordination and seeking to determine: “Did Donald Trump, through action or inaction, corruptly seek to obstruct or impede Congress’s official proceedings to count electoral votes?”

Meanwhile, the former president continues to try to hamper that investigation. Today, Trump’s lawyers added a supplemental brief to his executive privilege case before the Supreme Court. The brief claims that since the committee is looking at making criminal referrals to the Department of Justice, it is not engaged in the process of writing new legislation, and thus it is exceeding its powers and has no legitimate reason to see the documents Trump is trying to shield.

But also today, a group of former Department of Justice and executive branch lawyers, including ones who worked for presidents Ronald Reagan, George H.W. Bush, and George W. Bush, filed a brief with the Supreme Court urging it to deny Trump’s request that the court block the committee’s subpoena for Trump’s records from the National Archives and Records Administration. The brief’s authors established that administrations have often allowed Congress to see executive branch documents during investigations and that there is clearly a need for legislation to make sure another attack on our democratic process never happens again. The committee must see the materials, they wrote, because “[i]t is difficult to imagine a more compelling interest than the House’s interest in determining what legislation might be necessary to respond to the most significant attack on the Capitol in 200 years and the effort to undermine our basic form of government that that attack represented.”

Heather Cox Richardson

December 30, 2021 (Thursday)

In his inaugural address, Biden implored Americans to come together to face these crises. He recalled the Civil War, the Great Depression, the World Wars, and the attacks of 9/11, noting that “[i]n each of these moments, enough of us came together to carry all of us forward.” “It’s time for boldness, for there is so much to do,” he said. He asked Americans to “write an American story of hope, not fear… [a] story that tells ages yet to come that we answered the call of history…. That democracy and hope, truth and justice, did not die on our watch but thrived.”

As Congressman John Lewis (D-GA), who was beaten almost to death in his quest to protect the right to vote, wrote to us when he passed: “Democracy is not a state. It is an act, and each generation must do its part.”

Inside Story

Current affairs and culture from Australia and beyond

The concept of the ‘difficult’ (I use the phrase ‘troublesome) woman is one I used in my work on Barbara Pym’s novels and short stories, and anything that uses this concept resonates with me. So, here is a review of a book I would have liked to have read and reviewed.

Awkward squad

Books | “Difficult” women have often played key roles in feminist history

ZORA SIMIC 1 APRIL 2020

The history of feminism is packed with women who changed the world but have since been forgotten or cast out because they were in some way “difficult.” Take birth-control advocate and sexologist Marie Stopes, for instance. While she’s hardly disappeared from view — her name is attached to a worldwide sexual health organisation — her avowed support for eugenics and her egomaniacal personality mean she is not easily embraced as a feminist pioneer. Historians can provide context to make Stopes’s views more comprehensible, but she’s not going to cut it as a reclaimed icon in the same way as anarchist Emma Goldman, who now adorns t-shirts and tote bags. Goldman was “difficult” too, of course, but in ways more appealing to contemporary sensibilities.

In her refreshing pop history Difficult Women, British journalist Helen Lewis makes room for the likes of Stopes, one of the better-known figures profiled among an eclectic (though mainly British) group that also includes working-class suffragette Annie Kenney, trailblazing football player Lily Parr and Maureen Colquhoun, who in the 1970s became the first “out” MP in British history. The subtitle — A History of Feminism in 11 Fights — refers to how the book is thematically organised around various struggles (like divorce reform, the vote and access to education), most of which remain unfinished or ongoing business (sex, love, work and, perhaps especially, time). Hers is a productive approach — the examples are mostly confined to Britain but still have the capacity to surprise or even enrage, and every theme translates to Australia. While we have had no-fault divorce since 1975, they still don’t have it in Britain. Access to safe abortion remains an issue everywhere, and every victory is hard-won.

For readers attuned to feminist debate and conflict, the subtitle also suggests a history of feminists fighting each other over the best way forward. And while there’s certainly some of that, including Lewis’s sharing of her own exasperation with present-day “woke” culture and what she sees as its unreasonable demands, the real substance here is in her vivid accounts of a range of feminist causes and the women who have helped to advance them. Her appreciation of her subjects — even, or especially, when she disagrees with them or they’re not particularly likeable — is contagious.

Some of the difficult women are long dead, among them Caroline Norton, who began lobbying for women’s custodial rights in the 1830s when she lost custody of her own children after her husband George sensationally put her on trial for adultery. Or Sophia Jex-Blake, one of the Edinburgh Seven campaigners who won the right for women to study medicine in the 1870s (with the “proviso that lecturers did not have to teach them alongside the men”). When required, Lewis dutifully and sometimes performatively speaks to historians and visits archives, but she’s best in journalist mode, interviewing surviving “difficult women” or activists who continue the fight.

These include the formidable Erin Pizzey, possibly the most influential domestic violence campaigner of all. Pizzey would be a “feminist hero,” writes Lewis, if not for the fact that her theories about gendered violence have morphed so far from feminist analysis that her most receptive audience is now among men’s rights activists. Lewis offers a sympathetic and clear-eyed account, reinforcing the point that “Pizzey’s difficult relationship with feminism does not mean that she has to be written out of the story.”

Lewis is no feminist theorist, but mostly this works to the book’s advantage. She concludes with her own manifesto for difficult women, by which stage the point has already been well made. Of greater interest is how she brings different feminist activists, thinkers and texts together around a shared theme. In the chapter on time, she interviews sociologist Arlie Hochschild, best known for the sometimes-misused term “emotional labour,” about how her own experiences as a working mother informed books like The Second Shift (1989). Lewis also gives due credit to Selma James as a feminist visionary, noting that her 1952 pamphlet, “A Woman’s Place,” written from the perspective of a working-class, immigrant woman, anticipated Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique (1963) by over a decade.

Lewis’s ambivalence about the campaign for which James is most famous — Wages for Housework — makes for a layered and lively analysis, including for readers like me who gravitate more to James’s politics than those of Lewis. Nor does it preclude her from having a lightbulb moment about the Marxist influence on feminism. “It’s an odd quirk of history,” writes Lewis, “that most of today’s younger feminists know little about Marxism” yet “we have inherited an intellectual tradition steeped in it.”

The Marxist influence on feminism includes intersectionality, a feminist theory Lewis is better at applying than pontificating about. She offers, for example, a thoughtful and fresh account of Jayaben Desai, who as a recent South Asian migrant led the historic strike at the Grunwick film-processing lab in the mid 1970s. Elsewhere, Lewis wades into what she calls the “intersectionality wars.” As a high-profile, white, middle-class feminist in Britain, Lewis has been targeted as irredeemably privileged, but her lamenting of this treatment reads as more defensive than insightful.

Mercifully, she keeps that discussion short, otherwise it might have dated or limited the appeal of what is a pleasingly ambitious and wide-ranging feminist read. While immersed in it, and ever since, I’ve been imagining an Australian equivalent. As Lewis so effectively demonstrates, difficult women have been a driving force wherever feminism has taken root, and it’s important to honour them, flaws and all.

ZORA SIMIC

Zora Simic is a Senior Lecturer in History and Gender Studies in the School of Humanities and Languages at the University of New South Wales.

Reenvisaging racist artefacts

The following stories, an art gallery exhibiting racist art which had been destined for destruction, and the Robert E. Lee statue removed from its former public place being placed in the Black History Museum are exciting in their potential for a thoughtful discussion. The first was posted on Facebook by Roslyn Russell. With a Barbadian colleague she has been researching an 18th century artist, Agostino Brunias who also depicted slave societies. Catherine McCormack, Women In the Picture Women, Art and the Power of Looking, Icon Books Ltd, London, reviewed on 31 March, 2021, see Books: Reviews , debates the validity of continuing to exhibit misogynist paintings, by replacing ill informed sexist explanations with those informed by feminist understandings. This is another contribution to the debate supporting the notion that knowledge based exhibitions should replace arguments for destruction.

Gallery aims to reclaim narrative with its racist ‘casta’ paintingshttps://www.theguardian.com/profile/vanessathorpe

The Guardian Australian Edition Sunday 26 December 2021, Vanessa Thorpe

Curator of new show tackles racial stereotyping using depictions of scenes of colonial life in the Caribbean and South America

Vanessa Thorpe Sun 26 Dec 2021 18.30 AEDT

Exploring Leicester Museum & Art Gallery 12 years ago, trainee curator Tara Munroe came across a stack of discarded oil paintings. The troubling scenes they portrayed would go on to change the direction of her career and may soon alter wider attitudes to art history.

The paintings depicted wealthy colonial life in South America and the Caribbean, and had been marked for destruction by the gallery. But the images, which each subtly grade racial and social distinctions, spoke clearly and powerfully to Munroe.

“To me, they are beautiful paintings but they have a very dark message within them,” she told the Observer as she prepared for the first public display of the unrestored paintings, in Leicester in the new year.

Now an expert in black heritage and the director of Opal 22 Arts and Edutainment, Munroe has doggedly continued her research into the origin and meaning of the five rare late-18th-century works she found. First, she persuaded the city’s art gallery & museum to save the works that had originally been categorised as distasteful and irrelevant, then she started to try to discover who had painted them and why. In the last few months, she has won funding from the Heritage Lottery Fund to curate a further, bigger exhibition of the paintings in 2023.

The works are examples of a genre known as “casta paintings” and there is only one other collection in Britain. It is also thought there are only about 100 complete or partial paintings known of anywhere, making the Leicester find of international significance.

“I want to help people understand the history of racial stereotyping in the colonial era and how the colour bar actually worked. I’d also like to link it to the academic discipline of critical race theory,” explained Munroe. “I’m from a mixed Caribbean background myself, although I am paler skinned, and so I know it is important to study the way colour has been used. It is why the paintings connected with me so much,” she said.

The re-evaluation of the paintings Munroe put in train is an instance of allowing prejudiced art back into the visual arts canon, or even “un-cancelling”, and it remains an unorthodox, sometimes controversial approach.

Some of the terms used then are now regarded as offensive. “Mulatto is still understood,” said Munroe. “And there are others such as Lobo, or wolf, which was what someone half-Indian and half-black was called. I want to move away from these labels without losing the history, and to be honest I’m scratching my head about the best way to do it.”

Munroe, who grew up in Luton, has Chinese and African heritage, and recalls that at school fellow pupils would ask what she was. “My mother would just say ‘green with pink spots’, but that didn’t really help me,” she recalls.

Casta paintings date from the 1600s to the beginning of the 19th century and were designed to show race and class divisions in Spanish colonies. Facial expressions and physical attitudes all encode the hierarchy and status of the people painted, and sometimes racial mixtures are identified and inscribed on the canvas. The works Munroe found, which also express contemporary anxieties about racial mixing, were originally donated to the Leicester museum in 1852, by Joseph Noble, a lord mayor of the city.

“For me, perhaps the biggest interest to this story is how it shows that we see things differently when we come from a different perspective,” Munroe explains. “A lot of people had looked at these paintings before, and they were just being used to train picture restorers before they were destroyed. It was only because I was working there that I saw something in them. There is a new level of understanding that comes when you have different people working somewhere.”

After the restoration work is complete later next year, Munroe plans a series of events and lectures with the aim of understanding the progression of academic attitudes to racial identity.

Richmond’s Robert E. Lee statue will move to the city’s Black History Museum

December 30, 202112:42 PM ET

Crews remove the statue of Robert E. Lee in Richmond on Sept. 8. Pending city council approval, the statue and eight other Confederate monuments will be moved to Richmond’s Black History Museum.

Steve Helber/AP

The massive statue of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee in Richmond, Va., taken down in September, will be moved to the city’s Black History Museum, Gov. Ralph Northam and Mayor Levar Stoney announced Thursday.

The Black History Museum and Cultural Center of Virginia will take the 21-foot-tall statue of Lee and the pedestal it stood on, which became a rallying point for protests against police brutality in the summer of 2020. Eight other Confederate statues that were removed around the city will also be moved to the museum.

HISTORY

Conservators find books, coins and bullets in Virginia time capsule

“Symbols matter, and for too long, Virginia’s most prominent symbols celebrated our country’s tragic division and the side that fought to keep alive the institution of slavery by any means possible,” Northam said in a statement provided to NPR.

“Now it will be up to our thoughtful museums, informed by the people of Virginia, to determine the future of these artifacts, including the base of the Lee Monument which has taken on special significance as protest art.”

The museum will partner with The Valentine, the city’s oldest museum, to get input from the community on how the statues should be displayed. Before any of that can happen, however, the plan still needs approval from the city council.

The decision on what to do with its statues is part of a larger nationwide conversation on removing, replacing and renaming Confederate symbols — and questioning what remembering history looks like in a public space.

Richmond was capital of the Confederacy for most of the Civil War, from 1861 until 1865. And Virginia once had the most Confederate statues in the country.

In Charlottesville, Va., the city council recently decided its statue of Lee — the proposed removal of which helped spark the deadly Unite the Right rally in 2017 — will be melted down and turned into a public art piece, a project that will be led by the Jefferson School African American Heritage Center in town.

RACE

An Emancipation Statue Debuts In Virginia Two Weeks After Robert E. Lee Was Removed

Andrea Douglas, the center’s executive director, told NPR she hopes Charlottesville’s plans will help guide what other cities do with their Confederate monuments.

“Can we create something that defines the community in the 21st century? What does Charlottesville want to be? We describe ourselves as a city that believes in equity, that believes in social justice, so what does that look like in a public space?” Douglas asked.

“This is really not about erasing history. It’s about taking history and moving forward,” she said.

The Jefferson Davis statue will now reside in the black History Museum, Richmond, with appropriate information.

Aren’t those flowering gum trees beautiful! They make me think of May Gibbs’ Little Ragged Blossom.

LikeLike

They are amazing. I don’t know why the flowers are appearing it always used to be the book covers. Weird and wonderful technology.

LikeLike